As my earlier blog post laid out, I’m interested in looking at royal mausolea as sites of historical memory in the tenth and early eleventh centuries. Over the past year I’ve started to put together a database of known burial sites of as many royals as possible from the Merovingian, Carolingian, Capetian, Ottonian, Anglo-Saxon, and Lombard dynasties. It’s currently sitting at over 200 individuals but is still growing!

I’ve already seen some interesting information appear from collating this data – the rise and fall in popularity of certain burial centres, their re-appropriation by other dynasties, and broader geographical shifts in where royals were buried over time. There are some thematic trends as well; whether burials were in male monasteries, female monasteries, churches, or cathedrals; which sites had cults of certain royals established and promoted and how that affected who was later buried there; which burial sites had lay abbots and so on.

But, I’m also interested in thinking about the narrations of the past at these sites. Do we see dynastic memories being promoted at the sites which contained royal bodies? The short (and rather fence-sitting) answer is ‘sometimes’. There are absolutely some burial sites which produced narratives about the royal past and about the people whose tombs they housed: specific examples are Sainte-Genevieve in Paris; St Martin in Metz; Saint-Dagobert in Stenay; Saint-Pierre-le-Vif in Sens; Saint-Cloud in Paris; and Sainte-Corneille in Compiègne.

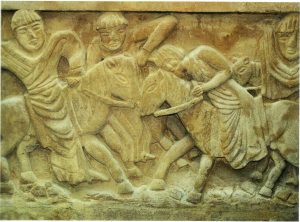

Carving of the martyrdom of St Dagobert II in the Crypte Saint-Dagoberte in Stenay. Image credit Wikimedia Commons. Image in the Public Domain.

Unsurprisingly, some of these locations are places where a saint’s cult grew up around the royal in question (Saint-Dagobert and Saint-Cloud, for example). This definitely shaped how those memories were presented. The vita of Dagobert II produced at Stenay, for example, is well-known as a case of a hagiography where the monks at the king’s burial site knew very little about their patron saint and so cobbled together a life that could be read on his feast day; in this case the cult gave form to the memory of the Merovingian past presented there. However, we also have to consider the importance of Stenay and of Dagobert II to the tenth-century Carolingians: Dagobert’s feast day was included in Queen Emma’s psalter, and Stenay was one of the few locations that we know formed part of this queen’s dower lands. Gerbert of Aurillac also referred to battles over who controlled the town in the late tenth century. If cult shaped the memory of the Merovingians there, did the Carolingians in turn shape the cult? Can we see hints of Stenay becoming a focal point of royal legitimacy from another dynasty?

Another interesting case is of a site that not only claimed to have a royal foundation and burial, but also produced a series of influential commentaries on the royal present. By the early eleventh century, Saint-Pierre-le-Vif in Sens claimed that its founder was a daughter of Clovis I, Theudechild, who was buried in the church*; a monk of the monastery, Odorannus wrote not only the Origo, actus et finis domnae Theudechildis reginae et constructio monasterii S. Petri, but also a chronicle that depicted the recent history of the West Frankish dynasty in detail which included a counter-point to the recently polemic account of the Capetian dynasty’s accession to the throne, the Historia Francorum Senonensis. This anonymous text from Sens claimed that Hugh Capet had rebelled against the crowned Carolingian king, Charles of Lotharingia and had tricked Charles into being captured before claiming the crown for himself. Odorannus, who had a very close relationship with Robert the Pious himself, tried to stem the damage from this account to the Capetians, arguing instead that when Louis V was dying he had given over the kingdom to Hugh; this favourable account of the rise of the Capetian dynasty to the throne depicted them as the direct heirs of the Carolingians. Another final link to the royal past at Saint-Pierre-le-Vif came in the form of Louis, son of Charles of Lotharingia; the last of the Carolingian dynasty, Louis became a monk at the monastery just before he died, gifting the monastery a pallium. His epitaph, recorded by Odorannus, recalled Louis as ‘regali de stirpe natus’: born from a royal family. Merovingian, Carolingian and Capetian royal identities all collided in early eleventh-century Sens.

Fragment of an 11th/12th-century Carolingian Genealogy from Lorsch. Image credit, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

But what about the sites that forgot, either accidentally or on purpose? We have glimmers of those too. At Lorsch, the burial place of Louis the German and Louis the Younger, we see the immediate use of the site by Arnulf in the late ninth century as a dynastic centre, a source of Carolingian legitimacy. Yet, as the tenth century wore on, there was little notable attention paid to the Carolingian bodies present at Lorsch. Later though, in the eleventh or possibly twelfth century, we see something interesting: a genealogical table of the Carolingian kings starting with Pippin, running through to Louis the German who is given a label ‘imperator sepultus Lauresham’ and his son, Louis the Younger, ‘iterum sepultus Lauresham’. Was this an attempt to work out which Louis was which? Or was the community at Lorsch well aware of which kings they housed during the tenth century, but only began to emphasise their Carolingian tombs as a result of a resurgence of interest in the Carolingian dynasty in the eleventh century? In Wipo’s Life of Conrad II, for example, we see an attempt to claim Carolingian descent for the new Salian dynasty through Conrad’s wife Gisela. Interestingly, amongst all the Pippins, Charles’s and Louis’s in this table from Lorsch, we also see another name – Otto, written in capitals on the top third of the page, just under a missing corner of the page. But which Otto? Why include him on this Carolingian table? Was there another family tree in the now-lost corner? There are many questions about Lorsch’s view of the Carolingian past that I’m still mulling over.

This brief look at some of the case studies I’ve uncovered has only scratched the surface; the way that major burial centres like Saint-Denis, Saint-Rémi at Rheims, Saint-Germain-des-Près, Compiègne, Metz and Aachen worked in the tenth/eleventh centuries provides much more material still.

*Theudechild was not a daughter of Clovis, but a granddaughter; her father was Clovis’s son, Theuderic I (d. circa 533).