This blog post is a translation of a text from the 1080s. It’s a little late for the After Empire project, but an important witness to the changes which mark the end of its remit, and to the transformation of the Carolingian and classical Roman pasts in central-medieval memory. It’s a follow-up to my previous blog post, a translation of a text which may, according some scholars (although others disagree), reflect concerns surrounding the Synod of Sutri in December 1046. At Sutri, King Henry III of the Germans formally deposed Pope Gregory VI, and appointed in his stead a German bishop, who became Pope Clement II, and promptly crowned Henry Roman emperor. There were grumblings about Henry III’s intervention, but, for the most part, posterity thought well of it. The present translation concerns events of nearly forty years later, when the fractious relationship between King Henry IV of the Germans (1056–1105) and Pope Gregory VII (1073–85) reached its lowest point. King and pope had both deposed each other from afar, but with limited practical effect. In 1081, the king entered Italy with an army, and with his own preferred candidate for the papacy, Archbishop Wibert of Ravenna. In 1084, after a long siege, Gregory VII was driven out of Rome, Wibert enthroned as Clement III (1080/84–1100), and Henry IV crowned emperor of the Romans.

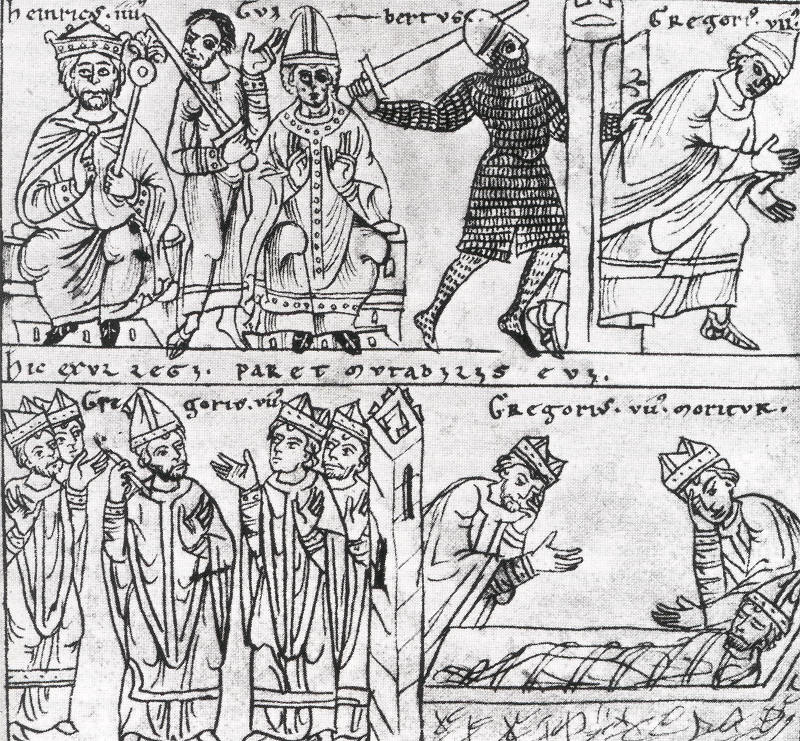

Gregory VII is exiled by Henry IV and Antipope Clement III (from Otto of Freising’s History, in the manuscript Jena, Thüringer Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Bose Q. 6 (s. xii). Image credit Wikimedia Commons, image in Public Domain.

In some respects, these events mirrored those of 1046 with almost parodic similarity: again, a King Henry intervened to depose a Pope Gregory and replace him with a Pope Clement, who then crowned the king emperor. But the second occasion came to be remembered quite differently: a disgraced, excommunicated king replaced a legitimate, reformist pope with a heretical impostor. History repeated itself: first as triumph, then as fiasco. A few decades later, even Henry IV’s supporters would blush at the memory of his heavy-handed intrusion. His anonymous biographer, writing soon after the emperor’s death in 1106, interrupted his narrative at the point of Henry’s departure for Italy in 1081, to plead directly with his subject: ‘cease, I pray, oh glorious king, cease from this attempt to cast down the ecclesiastical head from his summit, to make yourself a criminal by recompensing injury!’. According to Henry IV’s grandson Otto of Freising, writing in the 1140s, ‘the turbulence of this period carried with it so many disasters, so many schisms, so many dangers of soul and of body that it alone would suffice to prove the unhappy lot of our human wretchedness’.

At the time, however, the party of Henry IV and Clement III made a substantial effort to legitimise their takeover. We know most of this from longer legal and theological treatises, the famous polemics of the so-called Investiture Contest. But shorter documents played a part as well. One such document was the Decretum Hadriani, the ‘decree of Hadrian’, a text which purports to describe a synod held by Pope Hadrian I (772–95). To a modern reader, it’s a clumsy forgery: the introductory historical narrative is confused, tendentious, and at times quite wrong; the second part, which describes and excerpts Hadrian’s synod, is pure invention. But many medieval readers were convinced. The canonist Ivo of Chartres cited it in his Panormia (10951100), and it made its way from the Panormia into Gratian’s Decretum. The anonymous author of the Tractatus de investitura episcoporum (‘a treatise on the investiture of bishops’) made it a centrepiece of their argument. It was taken up by several reputable chroniclers—Landulf of Milan, Sigebert of Gembloux, William of Malmesbury, and others.

Exactly where and when the Decretum Hadriani was produced is disputed. It was traditionally seen as one of a group of forgeries produced in Ravenna in 1086, known as the ‘Ravenna forgeries’, but many scholars today reject both the coherence of this group and the attribution to Ravenna. Ian Robinson has suggested an origin in Trier, whilst the most recent editor of the text, Claudia Märtl, has proposed that the Decretum Hadriani might have been produced at an Italian pro-imperial centre, perhaps Farfa. Most scholars agree that a date in the 1080s is likely, although it is difficult to pin down exactly. For the Carolingianist, the Decretum Hadriani clearly has little historical value, and it could be read as a quite sad indictment of the state of knowledge about the eighth century in the late eleventh. A comparison with the so-called Privilegium Ottonianum of 962, which purportedly granted emperors the right to ratify papal elections, is instructive. But for those of us who are interested in the intricacies of the dispute between pope and emperor in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, it holds considerable interest. It’s a fascinating example of how the Henrician party attempted to recapture the moral high ground in the dispute with the papacy, by appealing to a Carolingian past whose historical meaning was slipping from the truthful into the exemplary, and merging in memory with the normative past of classical Roman law. It’s a witness to history being both forgotten and reconstructed.

Translation:

From the decrees of Pope Hadrian for Charles, king of the Franks.

In the time when the Lombards invaded Italy, they also occupied Rome; and, after entering the kingdom of Italy, they held it for twelve years without a king. From then on, they appointed kings of their own, and prevailed until the arrival of King Charles, who captured King Desiderius of the Lombards in Pavia after a long siege. His son Adalgis took flight across the sea. Until that time, there were representatives of the city of Constantinople who dwelled in Italy and Rome, and who occupied towns and exacted tribute; they sent this to the treasury of august Constantinople. However, they were expelled by the people of the Lombards, those Lombards who held the kingdom until the time of King Charles.

It happened, indeed, that King Liutprand of the Lombards besieged Ravenna and destroyed Classe. The exarch of Ravenna and the citizens of Ravenna called to Rome for help, and they set sail toward Constantinople. Later, King Aistulf of the Lombards invaded the exarchate of Ravenna, the exarchate of Istria, and the duchy of Ferrara, and seized Faenza and Cesena from the Roman church.

At that time, Pope Stephen sent envoys to Francia, to King Charles of the Franks, so that he, for the love of St Peter, might defend the holdings of the Roman church from such persecution. Charles, moved by piety, sent frequent envoys to King Aistulf, but nothing came of it: Aistulf enjoined to restore all goods, and promised satisfaction in all things, but did neglected all his promises. After the death of Aistulf, Desiderius obtained the kingdom, and still seized church property. Charles then sent frequent envoys to that king. Desiderius promised to give back all the goods of the church, but nothing came of it.

Pope Stephen had died, but Pope Hadrian sent legates to Charles and asked him to come to Rome for the defence of the holdings of the church. Charles then entered Italy, and besieged Pavia, where he left his army, and proceeded to Rome for the feast of the Holy Resurrection. He was honourably received by the blessed Pope Hadrian and all the classes of the Romans, who acclaimed him with the lauds of the city: ‘Life and victory to Charles, forever august, crowned by God’. After the feast of the Holy Resurrection he returned to Pavia, seized King Desiderius, and led him into captivity.

Having returned from there to Rome, Charles, together with Pope Hadrian, summoned a holy synod in the church of the Holy Saviour in the Lateran Palace. The synod was held, with great reverence, by one hundred and fifty-three of the most devout bishop and abbots, together with judges and teachers of law, from all classes and districts of the beloved city, and by the entire clergy of the holy church of Rome. They inquired into the practice of law and customs, and into which dissent and sedition they could banish from the apostolic see, from the patrician office, and from the Roman Empire. [Such divisions] were all the root of great error in the whole world. According to traditional practice, the Roman people would establish laws. But it was often difficult to make so many agree on one matter. Therefore they conceded their right and power to the emperor, as we can read: ‘the Roman people conceded to him and into his hands all its right and power’ [see Justinian, Inst. I:2, §§4–6].

Following this precedent, the aforementioned Pope Hadrian, with all the clergy and the people and the entire holy synod, granted to the august Charles all their right and power to elect popes and to arrange the affairs of the apostolic see. At they same time, they conceded to him the patrician office.

In addition, they decided that archbishops as well as bishops, in their respective provinces, should receive investiture from him. Following that, they should receive consecration from the appropriate person. Thus, old notions and habits shall be forbidden to later generations, in order that no one may be elected to episcopal office because of kinship, friendship, or payment. Instead, only a king shall be able to bestow such a venerable position. And a bishop who has been elected by clergy and people, whether presumptuously or for religious reasons, is not to be consecrated by anyone, unless he has been approved and invested by the king.

When everyone, who had gathered in this holy synod in the name of the Trinity, had given their opinion on this, Pope Hadrian conceded, approved, and established it with affirmation. And he added the following, to corroborate: ‘Should any man be found to have violated or resisted against what we just said, of whichever social position, class, order, office, or kin, then he shall know that he has fallen into the ire of St Peter, prince of the apostles, and of all the saints and our predecessors; he shall forever be condemned to the chains of anathema; and he shall suffer excommunication from the entire church and the whole Christian people. And if he does not repent from this evil, then he shall be punished with irrevocable exile or struck by capital punishment, and his possessions shall be confiscated. But he who is led by piety, and observes and watches over all these things, he will have merited the grace of blessing and eternal life with all the saints, without end, for ever and ever. Amen!’

References:

K. Jordan, ‘Ravennater Fälschungen aus den Anfängen des Investiturstreites’, Archiv für Urkundenforschung 15 (1938), 426–48; reprinted in his Ausgewählte Aufsätze zur Geschichte des Mittelalters, Kieler historische Studien 29 (Stuttgart, 1980), 52–74.

C. Märtl, ed., Die falschen Investiturprivilegien, MGH Fontes iuris 13 (Hanover, 1986).

Otto of Freising, De duabus civitatibus, ed. A. Hofmeister, MGH SS rer. Germ. (Hanover and Leipzig, 1912); The Two Cities: A Chronicle of Universal History to the Year 1146, transl. C. C. Mierow (rev. ed., New York, 2002).

I. S. Robinson, ‘Zur Entstehung des Privilegium Maius Leonis VIII papae’, Deutsches Archiv 38 (1982), 26–65.

W. Ullmann, ‘The Origins of the Ottonianum’, The Cambridge Historical Journal 11 (1953), 114–28.

—, The Growth of Papal Government in the Middle Ages (3rd ed., London, 1970), at pp. 352–8.

Vita Heinrici IV. imperatoris, ed. W. Eberhard, MGH SS rer. Germ. (Hanover and Leipzig, 1899); The Life of Emperor Henry IV, transl. T. E. Mommsen and K. F. Morrison in Imperial Lives and Letters of the Eleventh Century (New York, 1962).