In 933, Bishop Rather of Verona rebelled against his king. Together with the local count he invited Duke Arnulf of Bavaria and Carinthia to take over the Italian throne from King Hugh. Similar schemes had worked before: King Hugh himself had been invited to take over the Italian throne by another rebellious bishop in 926. Arnulf was, however, quickly repelled by Hugh, and Rather was imprisoned in Pavia for his treason. After two and a half years he was exiled to Como, where he remained under house arrest for a further two and a half years.

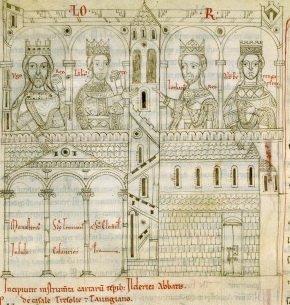

Four kings of Italy: Hugh, Lambert, Lothar and Berengar II (l-r) in Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 5411, fol. 129v. Image credit Wikimedia Commons. Image in the Public Domain.

It was while imprisoned and exiled in the years between 934 and 939 that Rather, one of the most prolific authors of the tenth century, wrote his largest work: the Praeloquia or ‘Prefaces’. Rather originally intended his work to form the ‘prefaces’ to a ‘handbook for Christ’s athlete’, but this work was never completed. Instead, the ‘Prefaces’ became the handbook itself. Yet the text is much more than a work of religious instruction: it can also be read as a justification for Rather’s rebellion, and as a targeted attack on King Hugh’s policies of patronage vis-à-vis his clerics.

A central point made by Rather in his Praeloquia is that the solidarity that once bound bishops had been broken in Hugh’s kingdom. He argues that clergymen should help each other, while ‘reciprocating our brother’s love in turn’. Rather warns King Hugh that when ‘the imprisoned (i.e. Rather) cry out, their fellows (consortes) cry for them too, being of one will in voice as in love’. Rather himself knew that this was wishful thinking. Not only he, but many other bishops had been oppressed by the king: ‘we bishops have been touched, scorned, driven, routed!’ Even though bishops should remain united when they faced such oppression, they were now divided and fighting amongst themselves. Rather worries that in his day and age ‘the prophet’s words are fulfilled in us: “Each will devour the flesh of his arm, Manasses Ephraim and Ephraim Manasses, and together they are against Judah!” (Is. 9.20) […] we are divided and forsaken, each by each.’

It was this breakdown of episcopal solidarity that, according to Rather, led to his fall. He argues that bishops have ‘permitted one of their own number (i.e. Rather) to be strangled by anyone in their presence with their mouths damnably hardened by one of the same rank’. With those words Rather implies that although some fellow bishops might have wanted to come to his defence, they were silenced by another bishop. This is likely a reference to Archbishop Hilduin of Milan, Rather’s erstwhile patron, and the person who had three years before arranged for Rather to be given to the Veronese as their bishop. In a series of chapters in the first book of the Praeloquia, Rather deals with the vices most likely to be committed by the social figure of the ‘patron’ (patronus). Building on several Old Testament verses, Rather stresses that the patron should above all ensure that his ‘hireling’ (mercennarius) is given proper repayment for his services. At the end of his discussion of the patron, the deposed bishop turns to a ‘certain foul vice’ committed by one patronus in particular against himself: Hilduin. Rather explains that he was ‘seduced’ by Hilduin to enter the latter’s service, but that was never given a worthy repayment for his support. Quite the contrary, Rather argues that Hilduin had tried to reduce him ‘from great success to monstrous failure’. The Milanese bishop’s ‘gains’ had increased with Rather’s ‘losses’. The deposed Veronese bishop therefore implies that Hilduin was involved with Rather’s fall, and was in some way rewarded for his efforts by King Hugh.

Hilduin had not only betrayed a fellow bishop, but had also been a bad patronus to Rather, his ‘hireling’. Interestingly, Rather also uses the term ‘hireling’ in his words to King Hugh, but does so in a very different way. The deposed bishop of Verona argues that Hugh was ‘an open robber of the Church’ who ‘would like no one to be found to oppose you’. This is, Rather argues, precisely why he rebelled: ‘you wanted to hold all the Church’s property and to have the bishop as your hireling (mercennarius), not the shepherd of Christ’s flock. He [Rather] objected to this and showed it by some kind of resistance.’ Here Rather’s use of the word ‘hireling’ goes back to a series of New Testament verses, in which the ‘hireling’ is contrasted unfavourably with the ‘good shepherd’. While the hired hand abandons the sheep when he sees the wolf coming, the good shepherd stays to protect his flock. Rather argues that he rebelled because he wanted to protect his church and its property against the rapaciousness of a greedy king. This also puts Hilduin’s betrayal of Rather into a new perspective: by being a ‘hireling’ to his patron, the king, Hilduin not only caused a fellow bishop to suffer imprisonment, but also allowed the property of the church to be stolen.

Additionally, Rather implies that bishops who behaved like ‘hirelings’ to their king were incapable of properly advising him. In contrast to Hugh, other contemporary kings were ‘Christian rulers’. Even if they would be tempted to act sinfully, as Hugh had done, their bishops would ‘sufficiently restrain’ them. King Hugh’s hirelings, on the other hand, had been ‘mute’ in the face of his many misdeeds against the church and its bishops. Rather also implies that bishops might have had good reason to remain silent: any bishop that dared to speak out to Hugh would be condemned, and invoke Hugh’s anger.

This invective must be seen from the context of Hugh’s policy of patronage. Recent studies on Hugh’s charters have suggested that the king sought to effectively undermine the power of bishops whose loyalty was in question by establishing ties of patronage with local groups. At the same time, Hugh attempted to further secure his power by installing loyal family members on important sees.

Hugh’s policy has rightly been called ‘innovative’. But to Rather, this was precisely the problem. His ideas on the bishop’s duty and his relationship to the king went back to a venerable Carolingian discourse on the episcopal office. At church councils in Paris in 829 and Aachen in 836, bishops had claimed the authority to guide the realm together with the king. According to the consensus reached at these councils, bishops were equally responsible for the moral good of the kingdom, and were expected to admonish the king if the latter was led astray. Rather makes the point that this age-old ideal could never be reached when bishops let themselves be used as hirelings to the king. Instead of subjecting to the king’s tyranny, they should close ranks and together correct the king for his faults.

In the years following his imprisonment, Rather would send his Praeloquia to several of his fellow bishops, asking them for their support in his quest to regain his see. Rather’s efforts appear to have borne fruit eventually, as he acquired the bishopric of Verona again in 946. During that same year King Hugh had suffered a final, fatal rebellion, a defeat in which several northern Italian bishops played a crucial role. He had been forced to return to the Provence by a pretender to the Italian throne, Berengar II, who would himself take over the royal title of the kingdom in 950. By that time Rather had again lost the see of Verona, forced into exile once more, but now as a result of mainly local opposition.

Although Rather’s career would remain troubled, his invective had undoubtedly posed a danger to Hugh’s moral legitimacy in the eyes of influential bishops, and this might have contributed to the king’s eventual fall. But more importantly, Rather’s invective was still read in the 950s, after Hugh had died. At the end of that decade, another ambitious cleric, Liudprand, was writing a recent history of the Italian kingdom. Liudprand lived in exile, having been forced to flee from Italy due to a conflict with Berengar II. He now worked in the service of the East Frankish King, Otto. Liudprand wrote his history to avenge himself upon Berengar II, but also in support of his own patron’s claim to the Italian throne. He had read Rather’s Praeloquia, approvingly noting that it was written with ‘sufficient humour and urbanity’. But Liudprand was not only amused by the Praeloquia: Rather’s portrait of Hugh and his hireling bishops also influenced how Liudprand wrote about Italian kings and his own patron. Liudprand narrates how both Hugh and Berengar II deposed God-fearing bishops in favour of their greedy cronies and kinsmen ‘with no council being held, no decision by the bishops’, thus enabling the sacrilegious robbery of church property. In contrast, Liudprand portrays King Otto as someone who defends the church against such oppressions, who admonishes those nobles who seek to rob churches and monasteries. Citing scripture to a particularly greedy count who wanted to be granted the Abbey of Lorsch, Otto argued that he would never give ‘that which is holy to the dogs’ (MT 7.6). According to Liudprand, Otto was thus a king that would not treat his clerics as hirelings. Unlike Hugh, he was no ‘open robber of the church’. In other words, Otto was a claimant to the Italian throne that bishops like Rather might finally get behind.

What Rather’s invective to King Hugh shows us, then, is that Carolingian notions of the episcopal office and its relationship to the king were still endowed with a great amount of power in a post-imperial world. Rather invoked this tradition in an effort to mobilise his fellows in the face of royal oppression, which might well have contributed to the loss of moral legitimacy and power faced by King Hugh. Still in the 950s, Liudprand evidently wanted to make clear that his own patron treated the church and its prelates very differently than recent Italian kings had done. In a world where bishops were potential kingmakers, rulers ignored episcopal calls for mobilisation against their misdeeds at their own peril.