Pessimism is depressingly common amongst modern British commentators upon standards in contemporary education. Public discussion, as in current concerns about the introduction of mandatory multiplication table testing in English primary schools, is always about the need to improve performance, in this case numeracy.

But, as early medieval scholars know only too well, the twin premises of this modern debate, that education matters and that standards need to be improved, are ones which would also have been very familiar to both rulers and churchmen in the early Middle Ages. They lie at the heart of Charlemagne’s call to the clergy in his Admonitio generalis (789) to correct ‘those things which ought to be corrected’, in which he specified how this should be done in some eighty-two chapters. This Carolingian programme of correctio generated a considerable number of texts across a range of genres including canon law collections, councils, capitula, laws, liturgical books, monastic rules and customs, penitentials and sermons. This Carolingian textual inheritance, as this project is exploring, provided a rich resource for their tenth- and eleventh-century successors. In previous posts by members of the Exeter sub-project we’ve explored some of the ways in which these successors sought to develop upon their Carolingian legacy. But more recently I’ve begun to explore how the interpretation of some aspects of this legacy were contested in the post-Carolingian period.

West Front, Verona Cathedral. Image credit, Wikimedia Commons. Image by Didier Descouens, published under CC BY-SA 4.0.

This aspect comes to the fore in the correspondence of Rather, bishop of Verona. In Lent 966 Rather wrote to his diocesan clergy, grumbling that he had summoned them three times to attend synod and each time found them to be ignorant. In a letter written later that year he relates the background to this one. He recounts how he had sent his arch-priest and arch-deacon together with the cathedral canons to conduct a two-day visitation of the parishes and ‘make examination’ and report back to him what ‘had to be corrected’. But, he complained that those conducting the visitation had focused on whether the priests knew the psalms ‘and such’ and had found that they did; however, when Rather probed, he discovered that ‘many of them did not even know’ the Apostles’ Creed. It was this ignorance which prompted him to send the Lenten letter to his diocesan clergy in which he instructed them to learn the three creeds and to recite them by heart when they were next summoned to the synod if they wished to remain as a priest in his diocese. He went on to instruct them on why the Lord’s Day is so called and how it should be observed, before quoting the text of the Admonitio Synodalis, a text which circulated widely in the tenth century which set out in detail the standards to be observed by the diocesan clergy.

Rather had a stormy and difficult relationship with the clergy of Verona, as well as the local count, which resulted in his leaving the see in 968. His account therefore needs to be read in the light of his unsuccessful attempts to impose his authority upon his diocese. But it is interesting here for what it reveals about the clash of educational standards between the Veronese higher clergy, who require the parochial clergy to know the psalms ‘and such’, and the Lotharingian-trained Rather’s expectations that they should know three creeds. For although Rather was dismissive of them, the Veronese higher clergy’s expectations about what local priests should know actually fits very well with Charlemagne’s programme of correctio as laid out in the Admonitio generalis. This enjoined in c. 68:

‘Let the bishops diligently examine the priests throughout their parishes, (about) their faith, their baptism and their celebrations of Masses, that the priests might uphold upright faith and observe Catholic baptism and understand well the prayers of the Mass. And that the psalms might be sung in a fitting manner according to the division of the verses and that the priests might uphold upright faith and observe Catholic baptism and understand well the prayers of the Mass. And the psalms might be sung in a fitting manner according to the division of verses and the priests themselves might understand the Lord’s prayer and preach for the understanding of all so that each may know what to request of God.’

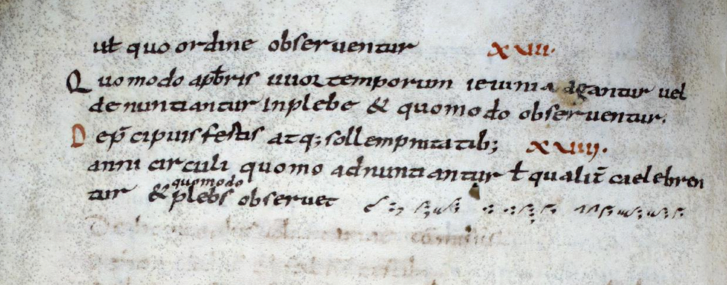

Bishop Waltcaud of Liège in his early ninth-century capitula adapted the Admonitio’s text into a series of questions including ‘The psalms, how they are to remembered and understood by priests.’ Waltcaud’s text was still being copied in tenth-century East Frankia: it’s probably mere accident but one later reader copied the neumes for a chant at the end of Waltcaud’s text in a manuscript now in Cologne, suggesting a link between the need to remember a particular chant and the contents of the text itself. In emphasising that the priests should know the Athanasian creed, Rather was also following in the footsteps of earlier ninth-century texts. Several Carolingian episcopal statutes advocate that priests should learn the Athanasian creed, and others provide for instruction in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds. What was at stake was not so much negligence as a difference of interpretation of these Frankish texts.

The Veronese clergy’s educational standards, in other words, were grounded in Carolingian traditions just as much as those of their irascible bishop, Rather of Verona.