It is a well-known story of early medieval monastic life that the Europe-wide diffusion of the Benedictine life-style was intrinsically connected to the Carolingians’ reform of the Church. This older form of religious life imposed its dominance over other male (and female) monastic rules in the Southwestern periphery of the Carolingian Empire from the reign of Louis the Pious and his monastic counsellor Benedict of Aniane. This second Benedict, originally baptized as Witiza, was the son of the Visigothic count of Maguelone in Southern France (Septimania). When he became a Benedictine monk in Saint-Seine (near Dijon) he took his new name from his Italian forerunner and model of monastic life, Benedict of Nursia. We know a relatively large amount about Witiza-Benedict, including his involvement in the general introduction of a revised version of the Regula S. Benedicti, and his own and his disciples’ works explaining the content and the superiority of this monastic rule in comparison to other concurring monastic rules. We even know that Benedict for a while preached against adoptionism, a Hispanic form of Christology favoured by bishop Felix of Urgell, which was disqualified, damned and eradicated as a heresy by the Frankish Church. Yet curiously, the transmission of his Life written shortly after his death (821) by his own pupil Ardo of Aniane (ca. 822/823) has left no traces in medieval Catalonia and seems to have been confined to his native region of Septimania, with a 12th-century copy from Aniane as the earliest preserved testimony of this biographical text (Montpellier, Archives départementales de l’Hérault, 1H1, fol. 1r–13v, soon after 1131).

Another well-known story of early medieval monastic life is the equally Europe-wide enforcement of the Benedictine life accomplished by the 10th-century monastic movements which originated in various Frankish reform centres such as Cluny, Gorze, Fleury, Moissac and others. These movements aimed to continue, complete or transform the reform work of Benedict of Aniane. At least two of these monastic centres, Cluny and Fleury, both with strong ties to the Carolingian culture, had an early impact on the renewal of Catalonia’s Benedictine life in forming first congregations of exempt communities since the second half of the 10th century.

Both stories of Catalan Benedictine monasticism are mostly told without an integral and integrative view on the manuscript tradition generated by these monastic reform movements. The full integration of these testimonies to a Europe-wide dissemination of new monastic literature into the history of oral and written communication and its effects on religious identity building in the various regions of the Iberian world is an exciting task still to be done in full detail. What now follows can only be some preliminary observations on the Catalan landscape of text transmission and on its historical contextualization.

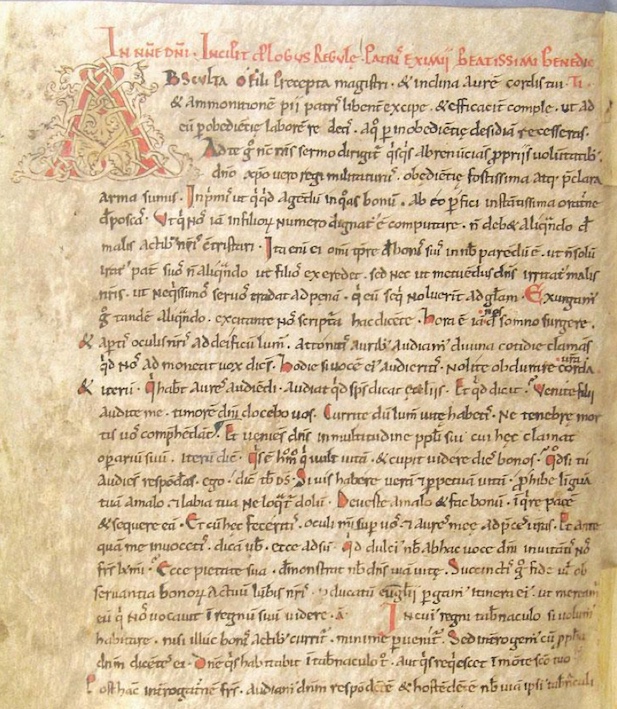

Regula S. Benedicti, Sant Cugat del Vallès, 11th century (Barcelona, Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Ms. Sant Cugat 22, fol. 135v).

At the core of previous research interest in Catalan Benedictine life is the fundamental text, the Rule of St. Benedict. The earliest known copy from ca. 850 is still written in Visigothic minuscule, but seemingly under influence of the Carolingian minuscule and thus produced somewhere in the Spanish March, today El Escorial, Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo, Ms. I. III. 13. Other early copies are seen from the 11th century: the inventory of Sant Sadurní de Tavèrnoles from 1040 mentions one, if not two copies of St. Benedict’s rule and the Ripoll catalogue of 1047 a “Liber Sancti Benedicti”, perhaps the (now lost) personal exemplar of abbot Oliba. Manuscripts of the rule from the same century have been preserved from the Benedictine houses Sant Cugat (given to its foundation Sant Llorenç del Munt), today Barcelona, Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Ms. Sant Cugat 22, and Santa Maria de Serrateix, now København, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Ny Kgl. Samling, Ms. 1794. During his preparations of the critical edition of the Benedictine rule published in 1960, the Viennese philologist Rudolf Hanslik could show that the text family of the rare Iberian testimonies depends on an archetype stemming from Narbonne or Septimania, the home region of Benedict of Aniane. But Hanslik did not compare the texts of all existing Catalan copies of the rule – the manuscript from Santa Maria de Serrateix in particular is missing in his edition – so we do not know the exact interrelationship between the Catalan copies and thus the ways of dissemination of Benedict’s rule in early medieval Catalonia.

Santa Maria de Serrateix

The Catalan Benedictine houses were also owners of a rich literature of commentaries and tracts on their father’s Rule and all of these belonged to the school of Benedict of Aniane and his followers, especially abbot Smaragd of St. Mihiel. This manuscript panorama shows the great impact of the Southern Carolingian-Septimanian network of monastic reformers which stood in open intra-Frankish conflict with older representatives of Benedictine life, especially the great Carolingian abbot Adalhart of Corbie. In the early 9th century, Benedict wrote his Concordia regularum, a synopsis of regulations taken from different monastic rules. In Catalonia, it is transmitted in an abbreviated text version (with lacunae) in a Southern French copy of the late 9th century, today Tarragona, Biblioteca pública, Ms. 69, which was later given to the Catalan Cistercian abbey Santes Creus.

In addition, though beyond our early medieval horizon, is Montserrat, Biblioteca del Monestir, Ms. 847, a 14th-century copy perhaps from Saint-Victor de Marseille, which transmits Benedict’s tract De diversarum poenitentiarum modo de regula Benedicti distincto, a special short comparative text on various monastic penitence practices.

Smaragd, stemming from a noble Visigothic family, who lived in the Iberian Peninsula or in Septimania, was abbot of St. Mihiel (near Verdun) since ca. 812 and wrote an explanation of the Regula S. Benedicti ca. 816/817, in the context of Benedict of Aniane’s reform. This Expositio in Regulam S. Benedicti must have played an important role in the Catalan monastic communities from the 9th century onwards: an early manuscript already seems to be mentioned in the testament of bishop Idalguer of Vic from 908. A single folium from a 10th-century copy from the Benedictine house Sant Benet de Bages (Manresa) is preserved as Montserrat, Biblioteca del Monestir, Ms. 793-I, and also the “Espositum regule” in the above-mentioned Ripoll catalogue from 1047 was most probably a copy of this commentary on St. Benedict’s rule. Finally, one has also to mention Smaragd’s famous monastic speculum, the Diadema monachorum, which is quoted in the testament of bishop Riculf of Elne (915) and later transmitted in a 12th-century copy from the Benedictine abbey Sant Cugat del Vallès, today Barcelona, Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Ms. Sant Cugat 90.

Smaragd of St. Mihiel, Diadema monachorum, Sant Cugat del Vallès, 12th century (Barcelona, Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, Ms. Sant Cugat 90, fol. 1v)

It would be much easier to identify further early manuscript material from the reform circle of Benedict and thus to understand better the relationship between our preserved manuscripts, if we had more reliable early palaeographical data from Benedict’s so-called Aniane scriptorium, postulated by Bernhard Bischoff in 1980, and if we knew more about the earliest products of the 9th– and 10th-century Benedictine houses of Catalonia.

I would like to close my short overview on early medieval Benedictine life in Catalonia with a 9th-century folium, unknown to the specialists of Carolingian Benedictine reform: this fragment, today Barcelona, Arxiu Capitular, Còdex 120, fragment no 2 shows glosses on the Rule ch. 5–7, thus on the spiritual core of the work. They are different from the most recently published work of an anonymous compendium on the Rule, the so-called Glosae de diversis doctoribus collectae in regula S. Benedicti abbatis, composed by an anonymous author ca. 790/827 who put together a catena-glossary of ca. 1100 elementary terms of the Regula Benedicti and a florilegium of more than 500 extracts from a wide range of biblical, patristic and monastic texts. Yet, our Barcelona fragment may have been part of a comparable school book of a new Benedictine community. In any case, it is a further testimony of Carolingian study of the Benedictine rule chapter-by-chapter, commenting central words or passages of the text. At the moment, we cannot say where exactly this manuscript was written. Its excellent 9th-century Carolingian minuscule however is that of a Carolingian writing community and the glossed text of Benedict’s rule belongs to the family of manuscripts disseminated by the church of Narbonne. Together with other fragments, it came into the older Uncial manuscript of Gregory the Great’s Homilies when it was rebound in the 10th century. The origin of this Uncial manuscript is seemingly Southern France near to the Mediterranean Sea, so that the fragments could also stem from this region. Yet, we cannot exclude the possibility that our Glossary on St. Benedict’s rule was already in Catalonia, because another fragment, a folium with excerpts from the Notitia apostolorum, today Barcelona, Arxiu Capitular, Còdex 120, fragment no 3, belongs to this region. The namedropping of bishop Vives (973–995) in this wonderful copy of Gregory’s Homilies could be the decisive hint that it came (together with the fragments) to the Cathedral after Barcelona’s raid by al-Mansur (985), as it was this bishop who had to restore the plundered book collection of his church.

I do not touch upon an even larger issue of Carolingian Catalan manuscript tradition here, to say which waves of the far richer Benedictine literature from the Carolingian Empire irrigated the monastic culture of early medieval Catalonia. The already available surveys of manuscripts show however that the Carolingian reform of liturgy introduced Carolingian Bibles and Homiliaries from the church of Narbonne and that the new monastic works from just all liberal arts and the multiple Carolingian exegetic schools where available in the early monastic schools of Catalonia as well.