From the last decades of the eighth century, the cult of the Archangel Michael spread throughout various Western regions and became a common European religious and spiritual phenomenon. Two important sanctuaries, Monte Gargano on the eastern coast of Italy and Mont Saint Michel in north-western France, invoked numerous pilgrimages at this time. A number of donations, bequests and testaments were made in favour of these sanctuaries.

The sanctuary of Monte Gargano apparently was established in the sixth or seventh century. A famous text that highlights for the first time the miracles done by the Archangel and thus emphasises the features of the saint is Liber de apparitione sancti Michaelis in Monte Gargano, written anonymously between the sixth and tenth centuries. This text went through big waves of diffusion in the Western European medieval world.

The Liber de apparitione (hereinafter Apparitio) is organised by three major episodes testifying the miracles of the Archangel: the story of a lost bull, the battle with pagans and the consecration of the cave on the mount of Gargano. It reveals numerous apparitions of St. Michael and the tangible evidence of them, mainly in the miraculously created church in the cave. Built upon this text, the Gargano legend is thus a keystone in the process of sanctification of the Archangel.

This Gargano legend passed by Catalonia, its traces can be revealed in the dating of the Archangel’s feast in liturgical books; in the circulation of copies of the Apparitio and in the iconography of this legend in the altar frontal of Catalan provenance.

The Feast of the Archangel in the Catalan liturgical books

The first mentioned feast in honour of the Archangel fell on September 29th, according to Jerome’s martyrology (Martyrologium Hieronymianum, 5th-6th century). This day is marked by the dedication of the church of St. Michael in Rome on Via Salaria. Another feast day of St. Michael is on May 8th. However, during the Middle Ages, this date had various origins, the principal one connected it to the apparition of the Archangel on Monte Gargano. Nevertheless, the attribution of the feasts to each of these dates was often confused.

The conserved martyrologies from Catalonia testify both feasts of the Archangel: on September 29th and on May 8th. The former date was followed by all Carolingian martyrologies and then was consequently copied by Catalan scribes. However, the latter date represents an addition in the margins of the martyrologies and then in their main text. The martyrologies from Girona, Vic and Sant Cugat contain the mentions: ‘Inventio domus sancti Michaelis archangeli apud Montem Garganum’ (Girona) and ‘Apud Montem Garganum invencio spelunce sancti Michaelis archangeli’ (Vic and Sant Cugat). The Tortosa martyrology presents another notice: ‘Ipso die memoria beati archangeli Michaelis’.

This persistent addition of the new feast in Catalonia resonated in other liturgical manuscripts. The sacramentary from Sant Cugat from the twelfth to thirteenth century has the common reference to ‘Inventio spelunce sancti Michaelis archangeli’ (Barcelona, ACA, Sant Cugat Ms. 47, fol. 8.). Another manuscript from the parish church of St. Roma dels Bons in Andorra (beginning of the twelfth century) delivers a following notice of the Archangel’s feast on May 8th in the calendar: “Inventio sancti Michaelis” (Montserrat, Biblioteca de Montserrat, Ms. 72, f. 3).

Apparently, from the tenth century onwards, the date of May 8th entered into liturgical Catalan books, coming from some exterior sources. The mention of ‘spelunce’ frequently attributed to this day appeals to the discovery of the cave on Monte Gargano and that of ‘domus’ could also imply the church in the sense of building. Thus, the feast of May 8th refers to a third episode of the Apparitio: to the miraculously dedicated basilica on Monte Gargano.

Catalan Apparitio

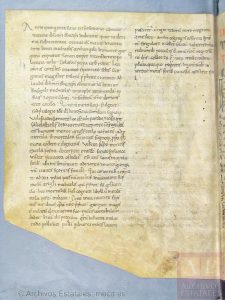

ACA, Ripoll, Ms. 74, fol. 156v

The Catalan scriptoria produced several slightly modified versions of the Apparitio. However, the fragment from Ripoll (ACA, Ripoll, Ms. 74, fol. 156v) seems to be the unique one due to new interpolations absent in other Catalan versions. Probably, it could have been copied from another source.

First of all, this Ripoll fragment contains a variation of the geographical data (not ‘Est autem locus in Campanie finibus’, but ‘in Apulie finibus’). Furthermore, the fragment has another beginning. It starts from the historical reference to the time of the Pope Gelasius that takes nine lines, and only afterwards the text continues with ‘et memoriam Beati archangeli Michaelis’. Finally, the most important consequence of this piece of text results in this passage at the very beginning with the date of May 8th: “Octavo idus Maias inventio erit beati Michaelis archangeli in Monte Gargano”. This sentence does not even mention the invention of the ‘basilica‘, or ‘domus‘, or ‘spelunce‘, but appeals metonymically to the Archangel himself. The presence of this dating in the Ripoll fragment from the end of the 10th to the beginning of the 11th century testifies that in Ripoll, May 8th had been already perceived as a liturgical feast in honour of St. Michael on Monte Gargano.

The dating of the Archangel’s feast in the fragments of hagiographical texts can also be explained by the surrounding feasts ordinated by calendar order. Therefore, in the fragment from Vic (ABEV, Carpeta X, n°6) the Apparitio text comes right after the feast of the Invention of the Saint Cross. This feast, according to the Ado’s martyrology, was celebrated on May 3rd. Such an order in the Vic fragment seems to be organized in a chronological way and thus attests the attribution of the St. Michael’s feast to the day of May 8th.

The feast of the Saint Cross on May 3rd was also indicated in the martyrologies and sacramentaries of the diocese of Vic. Following the principle of the codicological volume’s organisation, a hypothesis can be put forward, that the Apparitio joined together with the feast of the Saint Cross in the Vic copy bears witness to the celebration of the Archangel’s day on May 8th.

Thus, in the diocese of Vic as well as in the Ripoll monastery a new dating of May 8th for the liturgical feast of the Archangel could be connected to the diffusion of the Gargano legend.

Iconographical solution for the Gargano legend

Since the eleventh century, the Archangels had become one of the popular topics in Catalan iconography. Among eleven representations of St. Michael in the Catalan churches, there is one altar frontal dated by the thirteenth century that is the singular example of the Gargano scene in Catalonia.

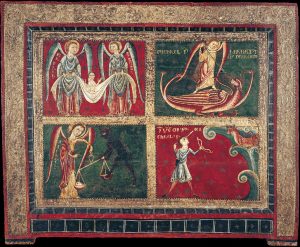

Altar Frontal of the Archangels. Image credit Museo Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Image published under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

The Altar Frontal of the Archangels (conserved now at the MNAC museum in Barcelona) was decorated between 1225 and 1250 and contained four scenes. The first scene is representing two other Archangels, Gabriel and Raphael, transporting the souls to heaven. Three others depict St. Michael struggling with a dragon, weighing souls with the devil and creating the miracle of the arrow and the bull, from the Monte Gargano legend. This last scene is named ‘Inventio sancti Michaeli’. The title coincides with the name of the feast on May8th in honour of the Archangel in the liturgical Catalan tradition. In the image, on the red background, a man (Garganus) is represented with an arrow in his eye, observed by a bull in the right upper corner. The miracle is thus happening before the eyes of the spectator. A particular feature of the Gargano iconography is therefore the absence of the Archangel himself on the image. According to the Gargano legend, the explanation of the miracle comes with the apparition of St. Michael in the dream of the bishop. The iconography though confines itself to displaying only the culmination part of the miracle, Garganus struck by his own arrow. This scene is also the only one on the altar evoking the name of the Archangel Michael but without his representation. The retable is thus a unique and curios example of the reception of the Gargano cult in Catalonia.

Therefore, on the altar, four episodes (the Gargano legend, the fight of St. Michael with the dragon, the Archangel weighing souls and Gabriel and Raphael in their psychopomp mission) together all embody the unity of the functions of the Archangels. St. Michael is represented twice in his warrior and eschatological symbolical dimensions. The obvious dominance of St. Michael among the archangels is emphasised by the remarkable Gargano scene revealing the miracles and the first apparition of the Archangel following the text of the Gargano legend.

Conclusion

Already from the mentioned sources it can be deduced that the legend of Monte Gargano had an important impact on the Catalan religious life in the central Middle Ages. The diffusion of the Apparitio played a particular role in this process of the Catalan adoption of the Gargano legend. This text, circulated in various European lands, was also known in different regions of Catalonia.

Besides, a new dating of May 8th can be observed in the Catalan liturgical production. Although this feast receives different nominations in the Catalan copies, it explicitly appeals to the events on Monte Gargano. The persistent mention of May 8th became a common phenomenon in Catalonia from the tenth century onwards.

All these factors bear witness to the reception of the Gargano legend in Catalonia. Different fields such as liturgical books and documents, iconographical and hagiographical sources demonstrate that the developing Archangel’s cult had several features from that on Monte Gargano. Probably, an explicit and final absorption of the Gargano tradition in Catalonia was expressed by the Altar Frontal of the Archangels of the mid-thirteenth century that divided at first all the functions of St. Michael and attributed a special place to the Gargano legend or, more precisely, Inventio sancti Michaelis in monte Gargano.