I looked at the numbers of submissions to the Royal Society journals in an earlier post. Here, we look at the relationship between the number of submissions, the rejection rate and the sustainability of peer review.

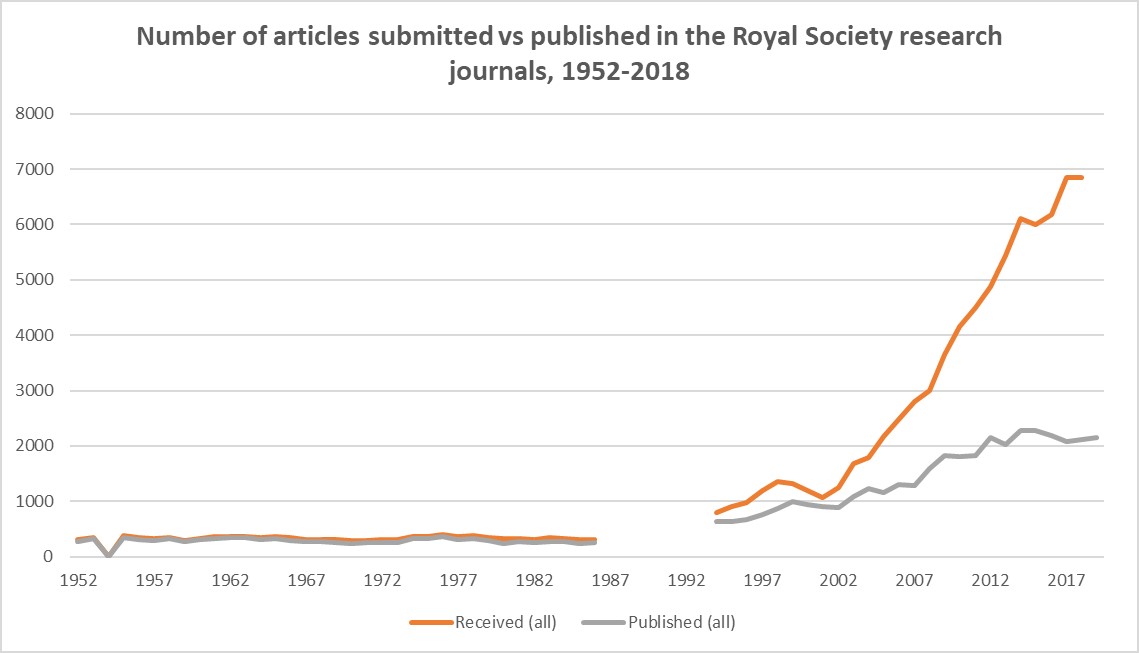

Graph 1 clearly shows two phases: a period when the Royal Society’s Transactions and Proceedings received a modest number of submissions, and published most of them; and a period when its journals received and published much more, but also rejected much more.

The transition point is in the gap in the data (for an explanation, see below): in 1990, significant changes were made to the organisation and scope of the Royal Society’s journals. Among them, and almost silently, the traditional requirement that papers could only be communicated via a fellow was finally dropped, and direct submissions became the norm. It meant that the Society’s journals were now open to a much wider pool of authors: no longer limited to those personal or professional networks intersected with those of one of the Society’s mostly UK-based fellows. The number of submissions rose; and would rise further in the early twenty-first century when the Society made a concerted effort to reach a global pool of authors.

The requirement for communication via a fellow had been experimentally (and briefly) removed in the mid-1970s. At that time, the editorial office reported that the result was more articles, but few worth publishing, and this was taken as evidence that the communication requirement was not a significant obstacle to the submission of publishable papers; and remained a valuable way of saving editorial effort by filtering out unpublishable papers.

The post-1990 experience suggests that the Society did manage to find significantly more papers worth publishing, but it is interesting that the biggest growth in submissions came in the early 2000s, rather than immediately after the removal of ‘communication’, i.e. it came after the Society made more effort at author-marketing. This suggests that, if you want to attract more papers from a wider diversity of people, simply removing an obstacle is not enough: you have to actively reach out to potential new groups of authors. By 2010, over 60% of authors in Royal Society journals were from outside the UK; it had only been 10% in 1950.

Increased submissions means an increase of editorial and reviewing work, to assess, select and improve the papers for publication. We have written elsewhere (Fyfe et al, 2020) about the challenges that faced the Royal Society’s editorial and review system in the early twentieth century, when the Society relied entirely on its own fellowship for reviewers. The problem of a limited pool of reviewers trying to cope with an expanding pool of submissions had been partly solved in 1969 when the Society began asking non-fellows to act as reviewers.

Graph 1 shows that the early-mid twentieth-century strains on peer review pale in comparison to those of the post-1990 period. It is also clear that the ‘cost/benefit’ ratio of editorial and reviewing work (in time and money) must be considerably higher in an era of high rejection rates, than it had been in the pre-1990 era.

Graph 2 shows the ‘effective rejection rate’: it includes all articles not published, though that may include articles withdrawn by their authors, or never resubmitted after revisions. Historically, the Royal Society’s rejection rate had been only about 10-15%, thanks to the filtering-out performed by the requirement that papers be communicated via a fellow. The post-1990 rejection rates certainly mark a different phase.

I remain intrigued, however, that rejection-rate graph is not as clearly divided into two phases as Graph 1: the rejection rate had already climbed to around 20% by the 1980s. Closer inspection suggests that this was due to changes in the Society’s A-side (i.e. physical sciences): in those fields, submission rates had been slowly declining since the 1950s, but from the mid-1970s, the rejection rate became higher than for the biological sciences.

Incidentally, the notion that a high rejection rate could be seen as a proxy for quality was definitely not present at the Royal Society before 1990, and nor was it apparent during the 1990s, when editorial staff regarded the newly increased rejection rate of 30% as a real worry, and a threat to the sustainability of the Society’s editorial and review processes.

Where do the data come from?

The data for 1952-1984 come from the Society’s annual reports: key performance indicators were regularly published in the Year Book of the Royal Society, and then (in the 1980s) in the Society’s Annual Report. The indicators included the number of papers submitted, and the number rejected. Earlier data on submissions survive, but not (easily) for rejections. The submissions/rejections in this first batch are for four journals: Philosophical Transactions series A and B; and Proceedings series A and B.

The data for 1994 onwards come from the Society’s current electronic database courtesy of Publishing Director Stuart Taylor. Re-submissions have been excluded for the period after 2000. The submissions/rejections in this batch relate only to the journals then defined as ‘research journals’. Thus, both Transactions are excluded (because they now carry invitation-only thematic review issues); but the new research journals (such as Open Biology and Interface are included).

The gap in the data arises from the fact that the Royal Society stopped publishing details of its number of rejections in the mid-1980s; and the electronic archive only goes back to the mid-1990s. The missing data probably survives in paper form, somewhere in the archive.

For more details on the earlier part of the story, see Fyfe, A., Squazzoni, F., Torny, D., & Dondio, P. (2020). Managing the Growth of Peer Review at the Royal Society Journals, 1865-1965. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 45(3), 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243919862868

One Reply to “More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s”