In 1963 the Royal Society coordinated a meeting of representatives from 55 British scientific societies. The topic for discussion was ‘Scientific Publications’, and to stimulate the discussion, there was some pre-circulated reading material: Dr Frank V Morley’s pamphlet Self-Help for Learned Societies (Nuffield Foundation, 1963).

The pamphlet was commissioned by the Nuffield Foundation at a time when those involved in learned society publishing were worrying about the state of their own finances, and wondering about the apparent competition from commercial publishers. Following a 1955 report by an experienced publisher, the Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society set up an advisory committee to further investigate the challenges facing learned societies. The Nuffield provided funding to hire a publishing consultant to visit individual societies.

From 1957, Dr Frank V Morley was that ‘liaison officer’. He was a Pennsylvanian-born Rhodes scholar, with a DPhil in mathematics from Oxford; but he was also an author and an experienced publisher, having been a director of Faber & Faber in the decade before the war (alongside T.S. Eliot) and then heading Harcourt Bruce in New York during the war. Back in Britain in the 1950s, he seemed to have the ideal combination of experience in science and publishing.

In 1963, he wrote up his experiences of visiting ‘individual bedsides’ of ailing patients. The language of illness reflects the premise that learned society publishing was in seriously ill-health in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Morley described 1955-63 as having been ‘lean years’ for learned society publishing.

Due to the social and economic changes in the postwar world, the old relationship between societies and their printer-publishers could not continue. There had been a lot of goodwill and generosity, but ‘there was no possibility of avoiding some change of habits’.

Morley saw the problem as ‘the general problem of production and distribution of those periodical publications which were essential for the encouragement and communication of original research, which nobody wished to go out of existence, but which without some kind of help were on the way to extinction’ (p.1)

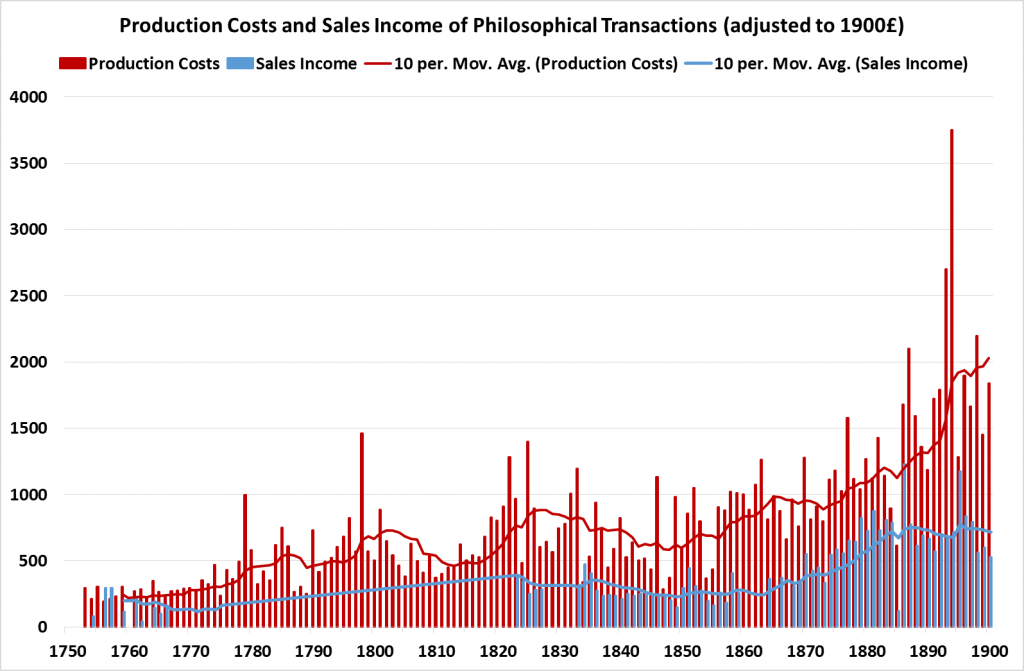

As the contents page reveals, he investigated the practicalities of editorial practices and production processes, the challenges of circulation (referred to as ‘promotion’ of the journal), and the long-term challenge of financial sustainability. His key message was that societies needed to pay more attention to sales income, so that they could make their journals self-supporting. (It’s worth remembering that learned society publishing before the war had usually been supported by a mixture of society funds and external grants, some from government, some from industry, others from private donors).

Morley urged societies to pay more attention to ‘practical publishing matters – some of them trivial and some by no means trivial’. As his title said, he was convinced that societies could do a lot to improve the state of their publication finances without needing to look to outside help, whether from government, private donors or arrangements with commercial publishers. David Christie Martin, executive secretary of the Royal Society, had made the same point in a lecture in 1957.

Morley was famously charismatic and funny, though some of the delegates at the June 1963 meeting found him pompous in person. We are still investigating the responses to the pamphlet: some found it patronising, but others found it helpful. (Do get in touch if you can help with this!)

Self-Help urged societies to learn how to run their journals more along the lines of commercial publishers; but it did not help with the question of the involvement of commercial publishers in setting up and owning their own journals. With regard to this question, the Royal Society proposed a Code for the Publication of New Scientific Journals at the same 1963 meeting.

[Images come from the copy of the pamphlet in the Howard Florey papers at the Royal Society, 98HF.160.2.8 ]