I looked at the numbers of submissions to the Royal Society journals in an earlier post. Here, we look at the relationship between the number of submissions, the rejection rate and the sustainability of peer review. Continue reading “More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s”

Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time

The Royal Society has been asking for expert advice on papers submitted for publication since the 1830s, and quality (or something like it) has always been one of the elements under consideration. Here, I investigate how the definition of ‘quality in peer review’ has changed over time.

Continue reading “Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time”

What was the function of early peer review?

What does peer review do? Every academic author nowadays is used to the process of receiving reports on their submitted manuscripts from independent experts consulted by the editor of the journal. Refereeing undoubtedly delays the publication of research, but it is widely believed to add significant value as a means of accrediting ‘proper’ research and researchers.

Amidst all the current discussions of the future of academic publishing, there lurks a strangely ahistorical view of the academic journal. It is not uncommon to hear that the peer-reviewed research journal has been at the heart of the scientific (and, by implication, scholarly) enterprise since the beginnings of modern science. But our research reveals that there is nothing natural, inevitable or timeless about the way academic research is published.

Continue reading “What was the function of early peer review?”

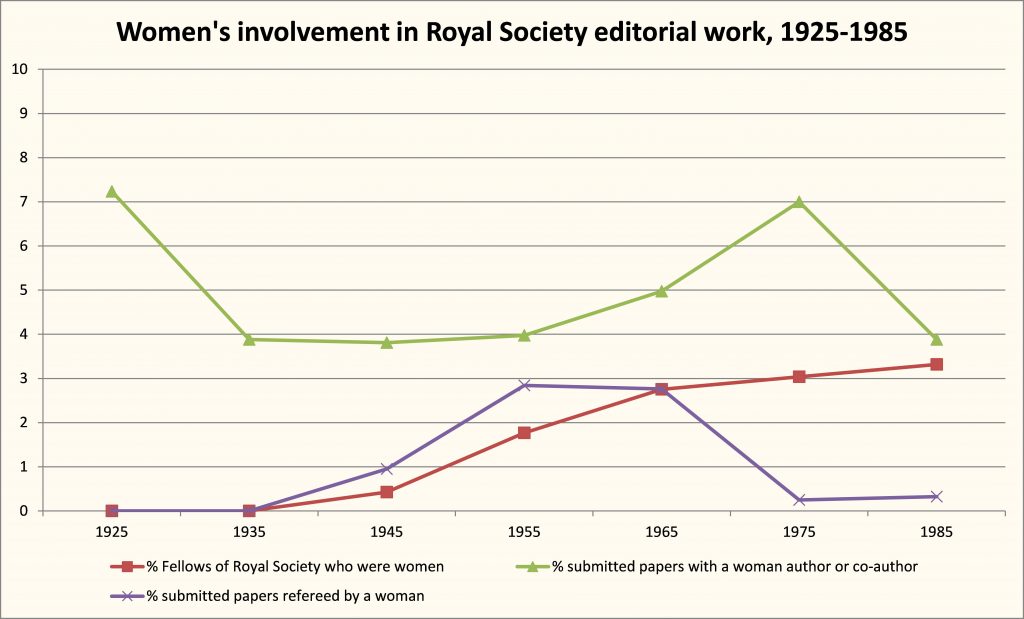

Then and now – exploring diversity in peer review at the Royal Society

This piece on the history of peer review at the Royal Society and the problem of unconscious bias originally appeared on the RS Publishing Blog, 10 Sept. 2018, as part of Peer Review Week 2018.

Peer review cannot be done by everyone. It can only be done by people who share certain levels of training and subject-expertise, and have a shared sense of what rigorous experimentation, observation and analysis should look like. That shared expertise and understanding is what should enable alert peer reviewers to reject shoddy experimental methods, flawed analysis and plans for perpetual motion machines.

But as we have increasingly come to realise, any group of people with shared characteristics may display unconscious bias against outsiders, whether that means women, ethnic minorities, or those with unusual methods. While peer review should exclude poor science, it should not exclude good research on the basis of the individual traits or institutional affiliation of the researchers, nor should it dismiss innovative approaches to old problems.

However, it seems socio-cultural and intellectual criteria have often been mixed together in the peer review process, and history can help us to understand why.

Continue reading “Then and now – exploring diversity in peer review at the Royal Society”

What history tells us about diversity in the peer review process

Continue reading “What history tells us about diversity in the peer review process”

1936: LNG Filon on the importance of journal reputation

“Research qualifications are now more and more insisted upon for appointments to academic and other posts, and appointing bodies have often no means of discriminating between important and trivial research, except the particular medium of publication. The publications of the Society have always been recognized as of exceptionally high standard, and special significance has been attached to papers published in them. Should such discrimination between publications become obsolete or even weakened, a spate of trivial papers may easily outweigh, in the minds of lay persons, a few really valuable contributions, with results ultimately detrimental to the best interests of Science.”

So wrote mathematician (and fellow of the Royal Society) Louis Filon, in the summer of 1936.

Continue reading “1936: LNG Filon on the importance of journal reputation”

Who are the referees?

As a rule, referees had to be Fellows. Only in 1990 (earlier?) did the Society officially allow non-Fellows to referee papers. [If there are earlier examples of non-Fellows could add here.] This meant that there was a finite number of available referees. The number of Fellows changed over time but in the mid nineteenth century, after reforms to reduce the size of the Fellowship, the number of Fellows was around 400 to 500. In reality, a very small proportion of the Fellowship was involved in refereeing. Those who were most active were typically past, current or future Council members. In other words, fellows who were active in one area of the Society’s service tended to be active in other areas too. During his Secretaryship, for example, George Gabriel Stokes was the most active referee, followed by his co-secretary William Sharpey. The Society’s Fellowship in the nineteenth century, when the number of practitioners in science in Britain was growing, represented only an elite group of the scientific community. At the same time, the majority of the papers submitted were from Fellows. Refereeing was thus about judging one’s peers, rather than making judgements on outsiders. Overtime this changed, and increasingly in the early twentieth century more non-Fellows submitted papers to the Society. Refereeing was still conducted by Fellows only but now many authors were not known personally to the Society’s Officers and Council. The Fellowship had grown, and now more Fellows were involved in refereeing: in the 1880s, 8% of the Fellowship were involved in refereeing; this rose to 30% by the 1930s. The workload, however, became even more uneven. The top most active 20% of referees produced just under 40% of referee reports in the nineteenth century, while the same % group in the mid-twentieth century produced 50% of referee reports. Getting a paper through the refereeing process at the Society signified acceptance by representatives of an elite national learned body of judges

1925: Printed referee report forms (used since the 1890s)

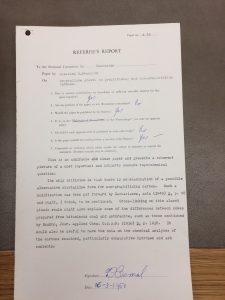

In the 1890s, the Royal Society had introduced a set of 7 questions for referees, in the hope of structuring the reports (which were sometimes extremely long-winded!). These were originally hand-written into the covering letter, but were quickly turned into a printed standardised report form, sent to each referee with the manuscript to be evaluated. Referees were encouraged to return their reports within 14 days – a deadline that was routinely breached.

By the early twentieth century, these report forms included clear instructions for referees, including advising them of the confidentiality attached to the papers referred to them (see image). It was routine for the author’s name to be written on the form: refereeing was single-blind, not double-blind. At this time referees were always Fellows of the Society (and their names and reports were kept confidential), but the majority of papers came from those outside the Fellowship.

The report forms made it possible for a referee to present an extremely succinct report, as was the case with Professor H. Lamb’s report on this 1925 paper by ‘Mrs. H. Ayrton’. Hertha Ayrton’s work in electrical engineering had previously been published with and exibited to the Society, but her status as a married woman had prevented the Royal Society accepting a fellowship nomination certificate in her name in 1902. (Her husband was also a well-known electrical engineer, and Fellow of the Royal Society, William Ayrton.)

The printed forms were also an attempt to standardize the refereeing process, or to at least advise referees on how to write an effective report. The Society never officially instructed referees until this date; referees were automatically expected to know how to write a report. Guidance on this continued to develop. By 1926, ‘Instructions to Referees’ was part of the Society’s Standing Orders.

Source: Box RR, 1925-1926, Royal Society Archives, London.

Printed referee report form (used since the 1890s)

In the 1890s, the Royal Society had introduced a set of 7 questions for referees, in the hope of structuring the reports (which were sometimes extremely long-winded!). These were originally hand-written into the covering letter, but were quickly turned into a printed standardised report form, sent to each referee with the manuscript to be evaluated. Referees were encouraged to return their reports within 14 days – a deadline that was routinely breached.

By the early twentieth century, these report forms included clear instructions for referees, including advising them of the confidentiality attached to the papers referred to them (see image). It was routine for the author’s name to be written on the form: refereeing was single-blind, not double-blind. At this time referees were always Fellows of the Society (and their names and reports were kept confidential), but the majority of papers came from those outside the Fellowship.

The report forms made it possible for a referee to present an extremely succinct report, as was the case with Professor H. Lamb’s report on this 1925 paper by ‘Mrs. H. Ayrton’. Hertha Ayrton’s work in electrical engineering had previously been published with and exibited to the Society, but her status as a married woman had prevented the Royal Society accepting a fellowship nomination certificate in her name in 1902. (Her husband was also a well-known electrical engineer, and Fellow of the Royal Society, William Ayrton.)

The printed forms were also an attempt to standardize the refereeing process, or to at least advise referees on how to write an effective report. The Society never officially instructed referees until this date; referees were automatically expected to know how to write a report. Guidance on this continued to develop. By 1926, ‘Instructions to Referees’ was part of the Society’s Standing Orders.

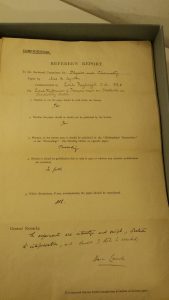

1951: Rosalind Franklin at the Royal Society

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (1920-1958) is becoming more known for her contribution to X-ray crystallography and the discovery of the DNA double helix. Brenda Maddox’ excellent biography, ‘The Dark Lady of DNA’ is key reading for anyone interested in Franklin, women in science, or the DNA-discovery saga. But because Franklin was never made an FRS, her times at the Royal Society have often been overlooked. In fact, she both visited, spoke and published with the Royal Society, as this example of a 1950s referee report shows. Note the questions referees are asked, and that the referees in question are JD Bernal and Dorothy Hodgkin, both huge names in the field by 1951. Franklin’s paper was well received by both, as you can see, and published by the Royal Society. Today, a photograph of a young, smiling Franklin hangs to the right of the main staircase when you walk into the Royal Society. Despite her lack of FRS status, her work was recognized by the Society in the fifties; – and today through the Rosalind Franklin award and lecture.