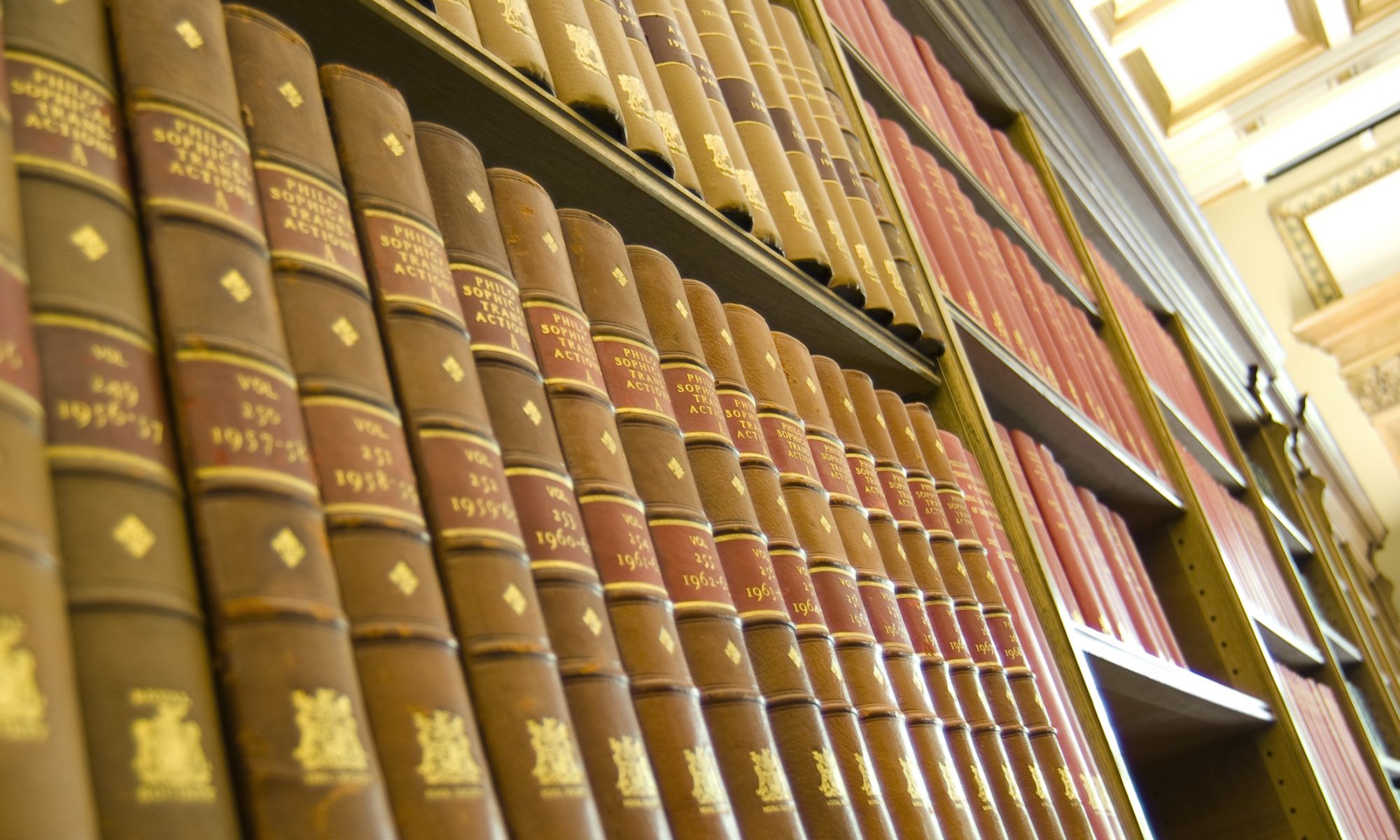

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Philosophical Transactions was the Society’s only publishing organ. This changed in 1832 when the Proceedings was established, first as a retrospective record of all papers published by the Society, and then soon after as a record of all papers read before the Society. Thus, if an author got their paper read before the Society, they were guaranteed a short abstract published in Proceedings. The Proceedings, however, was at times the location for full research papers, usually those too short to be considered for Transactions but longer than abstract length. This became an increasing practice towards the end of the nineteenth century. By 1914, the Standing Orders of the Royal Society were changed to reflect the different purpose of Proceedings. Now it would contain abstracts of papers published in the Philosophical Transactions, but the main content was papers ‘of approved merit not more than twenty-four pages in length, and not containing numerous elaborate illustrations’. The Philosophical Transactions was for ‘papers of approved merit which contain numerous or elaborate illustrations, or which cannot without detriment to their scientific value be condensed into the space reserved for papers in the Proceedings’. The other distinction was that papers for Transactions should be sent to two referees, while Proceedings papers <24 pages in length could be passed for printing without being referred.

The new Standing Orders simply formalised what had been the usual practice for several decades. They also marked, however, an important development which meant that the Proceedings was increasingly an attractive alternative to Transactions because of its shorter lag-time between submission and print due to the speedier decision making process that generally avoided referees. Some scientists were keen to take advantage of it, choosing the Proceedings to publish papers they would have submitted to Transactions fifty years earlier. In reality, some Proceedings papers were refereed, and increasingly so as the twentieth century progressed [some figures from Aileen’s peere paper?]. But initially, Proceedings remained less tied to the long refereeing process. The Proceedings was also attractive because it appeared in print more frequently than the Transactions, which was published biannually. By the 1920s Proceedings was monthly, although the publishing date remained unfixed. This meant that a paper could be submitted, read (even just its title), and sent to the printers within a few days, available in print within a few weeks, rather than a few months as was often the case with Transactions papers. The Transactions was therefore no longer the Society’s main publishing organ; the Proceedings was becoming a popular site for speedier publication. While the Transactions was attractive to authors because of its elaborate illustrations, the Proceedings provided a way to publish with the Society without sacrificing speedier publication.

Source: CMP/10, 21 May 1914, p. 428-440, Royal Society Archives, London.