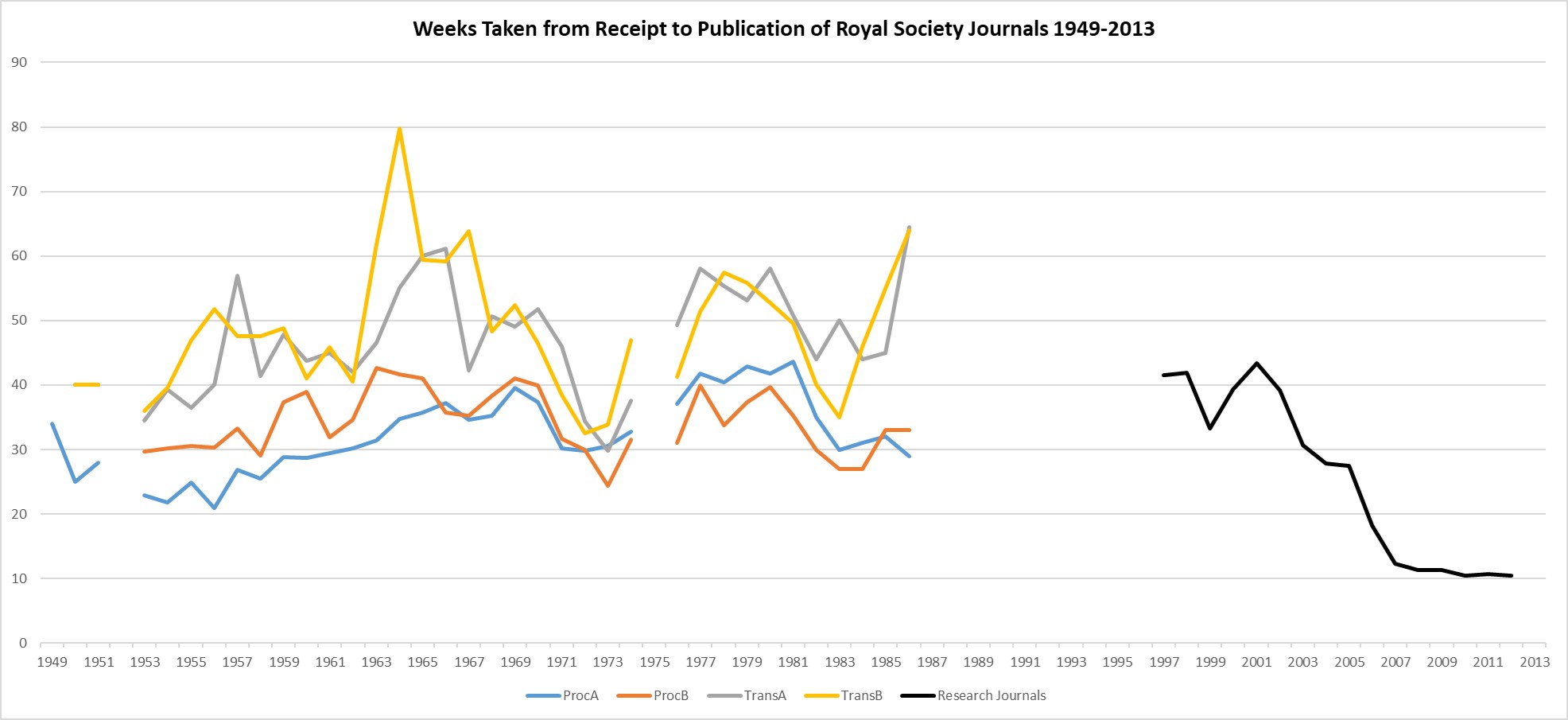

The time taken from receipt of a submission to publication is today frequently used as a ‘key performance indicator’ by academic journals. It is a (partial) measure of the speed or efficiency of the journal’s editorial and production processes (though also highly dependent on the author’s approach to revisions and proofs). The Royal Society has been recording and reporting this metric since the early 1950s, which allows us to produce the graph below:

The Proceedings in the 20th Century

The Proceedings of the Royal Society has been printed since early 1831, when it reported the activities (or ‘proceedings’) of the weekly meetings of the Royal Society. The first meeting reported was that for November 1830. For the rest of the nineteenth century, it carried a mix of content: reports of meetings; annual accounts; summaries of papers presented to meetings of the Societies (similar to abstracts); short stand-alone papers; and occasional longer papers full of data, deemed insufficiently ‘significant’ for publication in the Transactions.

Here, we present some overviews of the twentieth-century Proceedings.

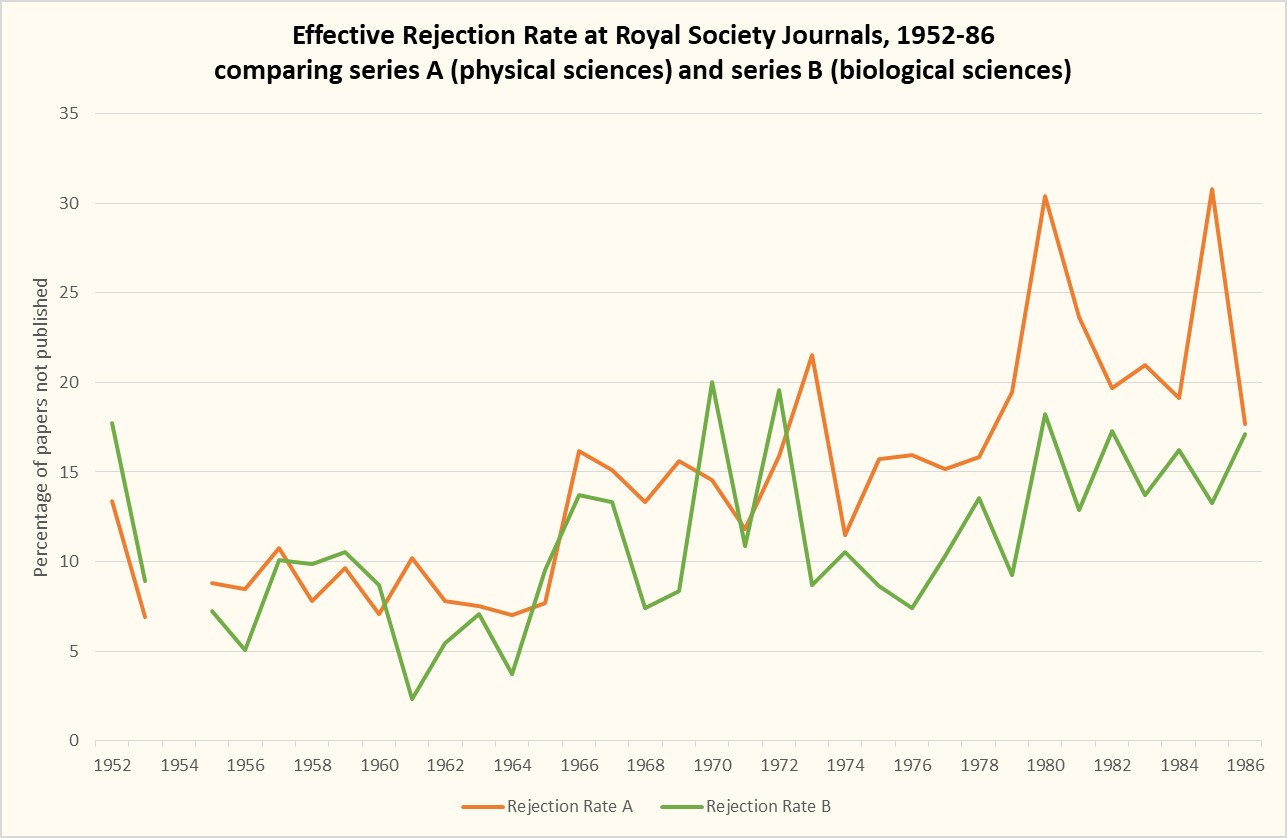

Rejection rates in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1950s-1980s

This graph offers additional detail on the overall rejection rates at the Royal Society’s Transactions and Proceedings in the second half of the twentieth century. As I discussed in that earlier post, the Royal Society historically had a low rejection rate (around 10-15%), due to the filtering-out of papers that was done pre-submission, since papers had to be submitted via a fellow. Continue reading “Rejection rates in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1950s-1980s”

More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s

I looked at the numbers of submissions to the Royal Society journals in an earlier post. Here, we look at the relationship between the number of submissions, the rejection rate and the sustainability of peer review. Continue reading “More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s”

Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time

The Royal Society has been asking for expert advice on papers submitted for publication since the 1830s, and quality (or something like it) has always been one of the elements under consideration. Here, I investigate how the definition of ‘quality in peer review’ has changed over time.

Continue reading “Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time”

What was the function of early peer review?

What does peer review do? Every academic author nowadays is used to the process of receiving reports on their submitted manuscripts from independent experts consulted by the editor of the journal. Refereeing undoubtedly delays the publication of research, but it is widely believed to add significant value as a means of accrediting ‘proper’ research and researchers.

Amidst all the current discussions of the future of academic publishing, there lurks a strangely ahistorical view of the academic journal. It is not uncommon to hear that the peer-reviewed research journal has been at the heart of the scientific (and, by implication, scholarly) enterprise since the beginnings of modern science. But our research reveals that there is nothing natural, inevitable or timeless about the way academic research is published.

Continue reading “What was the function of early peer review?”

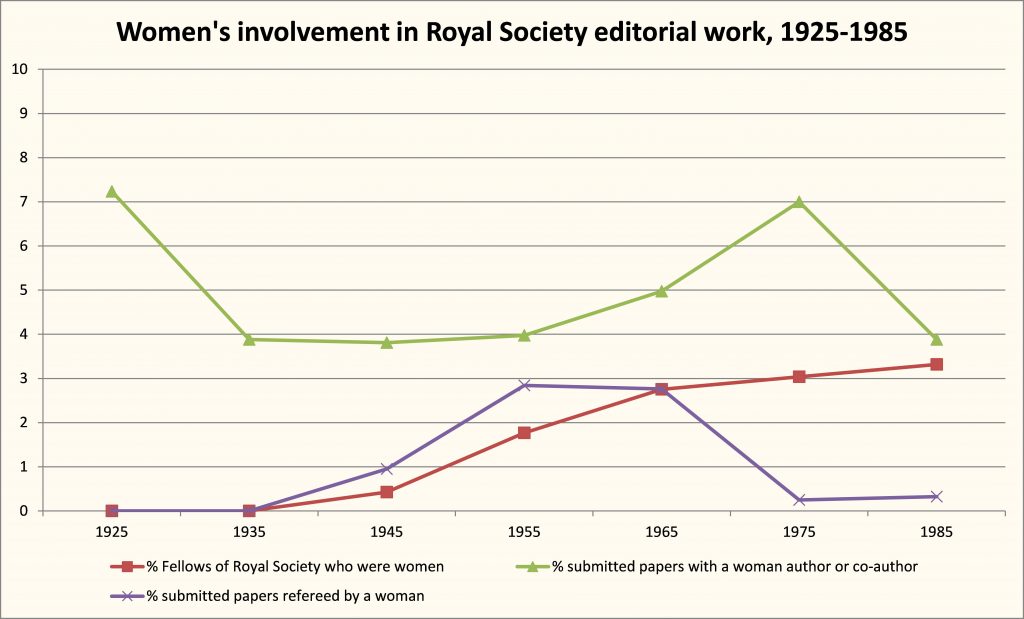

Then and now – exploring diversity in peer review at the Royal Society

This piece on the history of peer review at the Royal Society and the problem of unconscious bias originally appeared on the RS Publishing Blog, 10 Sept. 2018, as part of Peer Review Week 2018.

Peer review cannot be done by everyone. It can only be done by people who share certain levels of training and subject-expertise, and have a shared sense of what rigorous experimentation, observation and analysis should look like. That shared expertise and understanding is what should enable alert peer reviewers to reject shoddy experimental methods, flawed analysis and plans for perpetual motion machines.

But as we have increasingly come to realise, any group of people with shared characteristics may display unconscious bias against outsiders, whether that means women, ethnic minorities, or those with unusual methods. While peer review should exclude poor science, it should not exclude good research on the basis of the individual traits or institutional affiliation of the researchers, nor should it dismiss innovative approaches to old problems.

However, it seems socio-cultural and intellectual criteria have often been mixed together in the peer review process, and history can help us to understand why.

Continue reading “Then and now – exploring diversity in peer review at the Royal Society”

Ownership and control of scientific journals: the view from 1963

On 13 June 1963, the president of the Royal Society Howard Florey presented a ‘Code for the Publication of New Scientific Journals’ to a meeting of officers representing 55 British scientific societies.

In the light of subsequent developments in the management and ownership of scientific journals, the Code’s insistence upon scholarly control of academic journals is notable. It was written at a time when the growing involvement of commercial publishers in academic publishing was becoming visible.

“The present tendency for commercial publishers to initiate new scientific journals in great numbers is causing concern to many people. With the expansion of established sciences and advances into new fields and disciplines it is evident that new journals are necessary.”

Continue reading “Ownership and control of scientific journals: the view from 1963”

What history tells us about diversity in the peer review process

Continue reading “What history tells us about diversity in the peer review process”

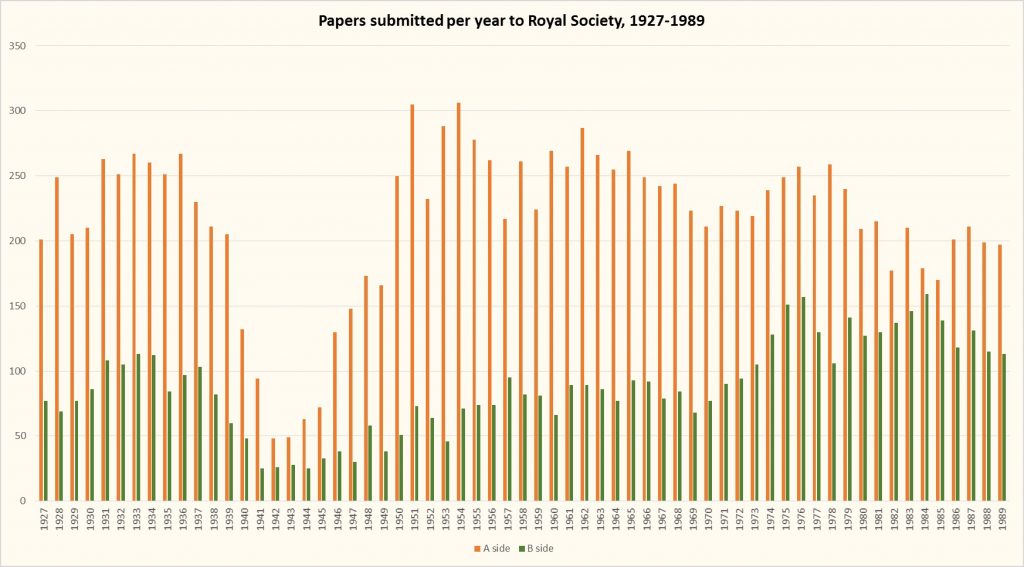

Submissions in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1927-1989

This graph shows the number of papers submitted to the Royal Society over the course of (roughly) the twentieth century. It includes papers that would ultimately be published in both Transactions and Proceedings, as well as papers that were never published.

Continue reading “Submissions in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1927-1989”