The history of the Royal Society is full of famous men and women of science, but every so often we discover a significant but obscure figure deep in the archives. These are often some of the most interesting people, and were better recognised by their contemporaries than we have remembered.

One such figure is Oliver Heaviside (1850-1925). Who? He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1891, specialising in electrical theory. His interest was sparked – pun intended – when he went to work with his uncle, Charles Wheatstone (1802-1875), co-inventor in 1837 of the first commercial telegraph. Telegraphy involved a code-system which was used to transmit a message between two distant sites, and its commercial expansion led to a series of national projects to lay lines across Britain, as well as attempts to connect Britain with North America and further afield. Communication was transformed, and it was through this new technology that Heaviside developed his passion for electrical physics.

Heaviside’s life has been of interest to some historians of science, and physicists might recognise his name, but he rarely comes up in a general history of the Royal Society. He was born in London into a modest family; his father was a wood engraver. After grammar school, where Heaviside excelled in natural history, higher education was not financially feasible. The young Oliver was sent to work with his brother in the north of England on the telegraph. In 1873 he sent the Philosophical Magazine a paper that was praised by physicists William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and James Clerk Maxwell, eminent figures at the Royal Society and experts on electrical physics. After just seven working years, Heaviside decided to quit and devote all of his time to the study of electrical theory, never again seeking full-time employment. He lived with his parents in London, and later in Devon above his brother’s music shop, spending the last few months of his life in a retirement home.

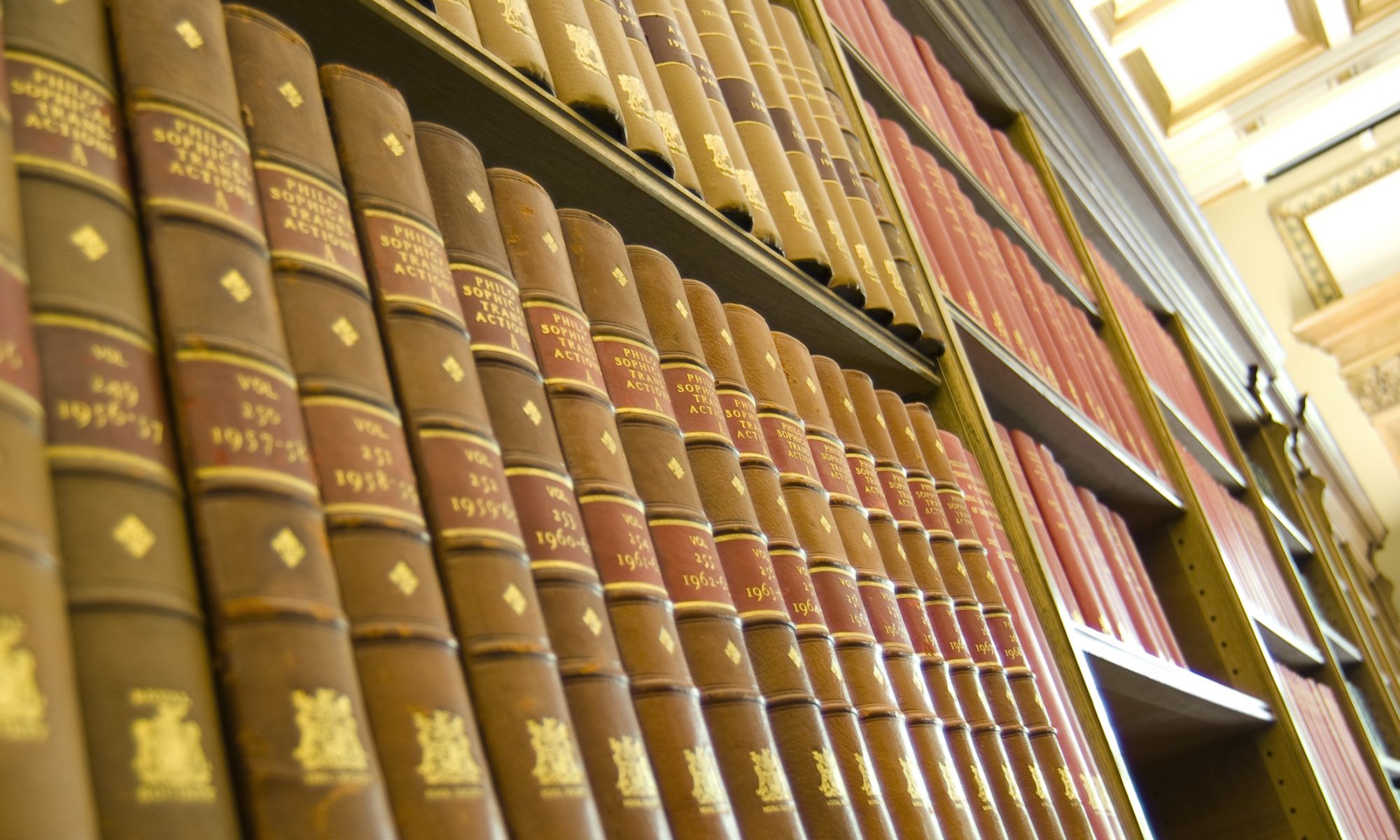

He published many articles throughout his life, mainly in the monthly Philosophical Magazine and the weekly Electrician, and it was through these papers that his work became recognised by other physicists in the Society, leading to his election to the Fellowship. It was only after this date that Heaviside published with the Royal Society – five papers in Proceedings and one in the Philosophical Transactions, all in the 1890s. Before this date he did not have the necessary connections to access the Society: if an author was not a Fellow they had to get the support of a Fellow to even submit a paper.

Even after his election, however, it was far from plain sailing for Heaviside at the Society. In June 1891, now a Fellow, Heaviside submitted a paper on the ‘Force, Stresses, and Fluxes of Energy in the Electromagnetic Field’. An abstract was published in Proceedings on 18 June 1891 on the same day the paper was read to the Society (Proceedings 1891 vol. 50 302-307 126-129), but the full paper was not passed by Council for printing in the Philosophical Transactions until October 1892, a delay of fully sixteen months from its submission. At this point the paper was available as a ‘separate copy’, which Heaviside could circulate among his contemporaries and interested readers could purchase from booksellers; the paper only appeared in the bound Transactions volume in 1892.

A delay between submission and printing was not unusual in the nineteenth century, in fact it was normal for an author to have to wait several months for a paper to pass through the refereeing process at the Society. This was not the cause of the delay to Heaviside’s paper; rather, he held up the printing of his paper himself due to his dissatisfaction with the printer’s typesetting of the copious mathematical formulae in the first copy he received. He was adamant that a better attempt be made, which he related to the Secretary of the Society John William Strutt (Lord Rayleigh): ‘the paper is hard enough to read without the unnecessary difficulty of unsuitable type, and I thought something must be done’ (MM/17/110).

Not only did such revisions to papers cause delay, but they were also expensive for the Society. Despite this, the Assistant Secretary appeased Heaviside, stating that Harrisons, the Society’s printer, ‘must do what they can to meet his wishes about the type’ (NLB/5/1076). Heaviside drew on his experience of publishing in the Philosophical Magazine and the Electrician to suggest the correct type to use. This is significant since the Society’s printing, until the work passed to Harrisons in 1877, had been done by Taylor and Francis, a company known for skilled typesetting of scientific papers. After months of to-ing and fro-ing between the Society, Heaviside and Harrisons, the Assistant Secretary believed an end was in sight: ‘we have got as near as we can to your [Heaviside’s] pattern’ (NLB/5/1166). In reality, Heaviside was still unhappy. The Society was now very anxious to get the paper out, but another four months passed before it was finally approved by Heaviside.

Heaviside never published another paper in the Philosophical Transactions. And even though he published several short papers in the Proceedings, when he attempted to publish here in 1894 he faced opposition from the referee, and was given the option to “withdraw” the paper: ‘I should, with much reluctance, prefer to withdraw it’ (rather than have it fester in the ‘archives’ of the Society where all unpublished papers resided) (RR/12/136).

Heaviside seemed to maintain his eccentricities in his personal life too. Without a job, he was exceedingly poor, only surviving on a small pension acquired for him by some Royal Society Fellows, which he was reluctant to accept. His work, however, was revered by other physicists at the Society, who were all formally educated and most in full-time academic positions. While his skill and intellect conceivably approached the likes of James Clerk Maxwell (whose theories he developed), his fame never did. The Royal Society’s archives may hold no portrait of Heaviside, but they do provide insight into the scientific merits of a Fellow who remained (possibly out of choice) on the margins of the scientific elite.