How has the average length of a scientific article changed over time? The answer depends on the purpose of the ‘article’ (a letter, a preliminary announcement, a fully-detailed research monograph); the space available in the printed journals; and the contemporary fashion for scholarly writing. But here, nonetheless, are some insights from the history of Royal Society publishing. Continue reading “Length of articles in Royal Society journals”

The Royal Society’s ‘other’ journals

The Proceedings and the Philosophical Transactions may have been the Royal Society’s best-known periodicals in the twentieth century, but they were not its only ones. It also published (and publishes) a number of periodicals aimed largely at an internal audience of Royal Society fellows. Here is what we know about their circulations. Continue reading “The Royal Society’s ‘other’ journals”

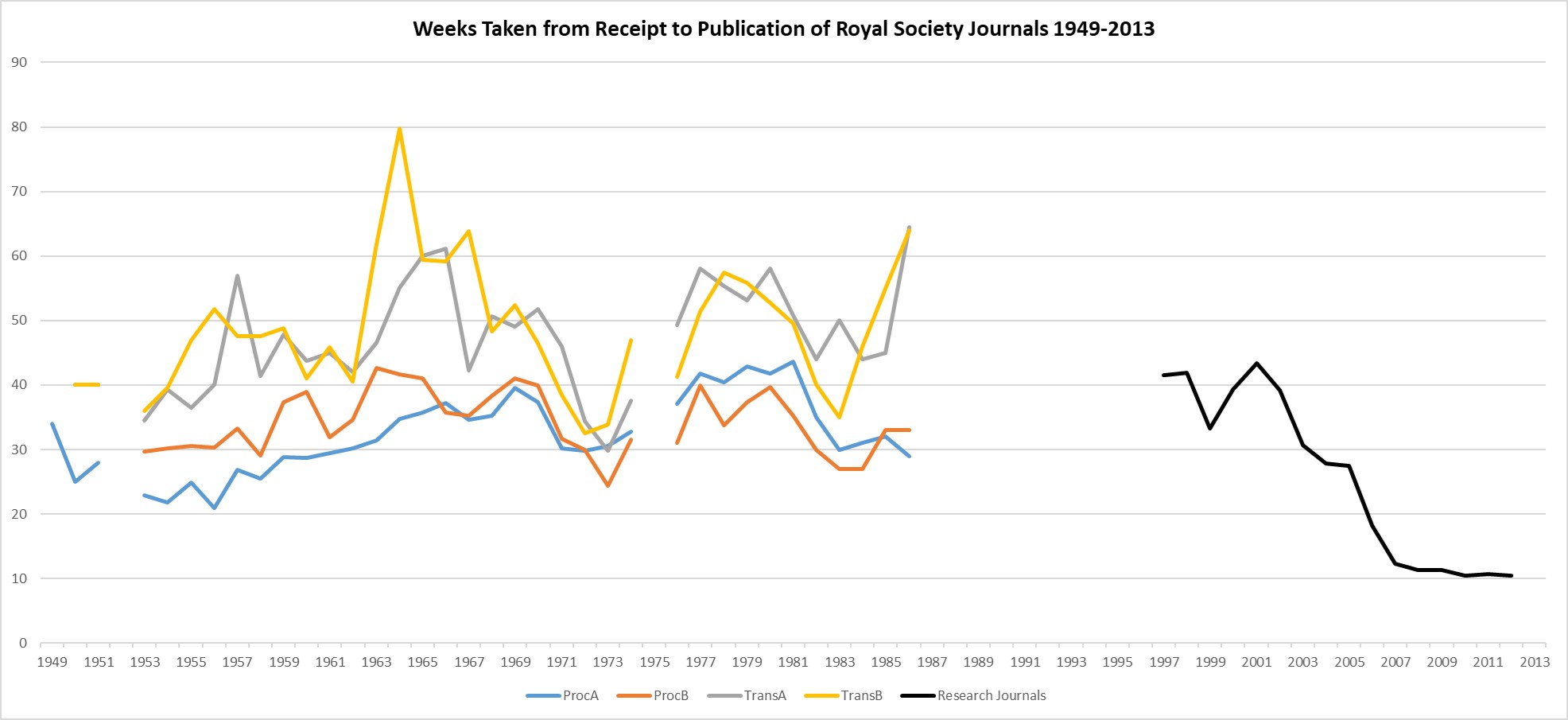

Time Taken to Publish

The time taken from receipt of a submission to publication is today frequently used as a ‘key performance indicator’ by academic journals. It is a (partial) measure of the speed or efficiency of the journal’s editorial and production processes (though also highly dependent on the author’s approach to revisions and proofs). The Royal Society has been recording and reporting this metric since the early 1950s, which allows us to produce the graph below:

The Proceedings in the 20th Century

The Proceedings of the Royal Society has been printed since early 1831, when it reported the activities (or ‘proceedings’) of the weekly meetings of the Royal Society. The first meeting reported was that for November 1830. For the rest of the nineteenth century, it carried a mix of content: reports of meetings; annual accounts; summaries of papers presented to meetings of the Societies (similar to abstracts); short stand-alone papers; and occasional longer papers full of data, deemed insufficiently ‘significant’ for publication in the Transactions.

Here, we present some overviews of the twentieth-century Proceedings.

The Transactions in the early eighteenth century

How much difference does the identity of the editor make to the content of a journal? In the early eighteenth century, the answer was ‘quite a bit!’. The first editor of the Philosophical Transactions, Henry Oldenburg had died in 1677, and subsequent editors had a tendency to reinvent the periodical (consciously or not) to suit their own interests or editorial abilities. Here, we present a series of charts to illustrate how the Transactions changed under the various editorial regimes of the early eighteenth century.

Continue reading “The Transactions in the early eighteenth century”

Where did the practice of ‘abstracts’ come from?

Academic authors in the twenty-first century have become used to submitting an ‘abstract’ of their paper alongside the full text – but abstracts were originally something written by another person.

Third-party summaries

The practice of ‘abstracts’ arose from a recognition of the value of providing short summaries of a paper, for the benefit of those people who were not able to access the full original. For instance, in the late 18th century, the Royal Society used the term ‘abstract’ to describe the summary of a paper that was written into the minute-books by the secretary after a paper had been read out loud at a meeting. Continue reading “Where did the practice of ‘abstracts’ come from?”

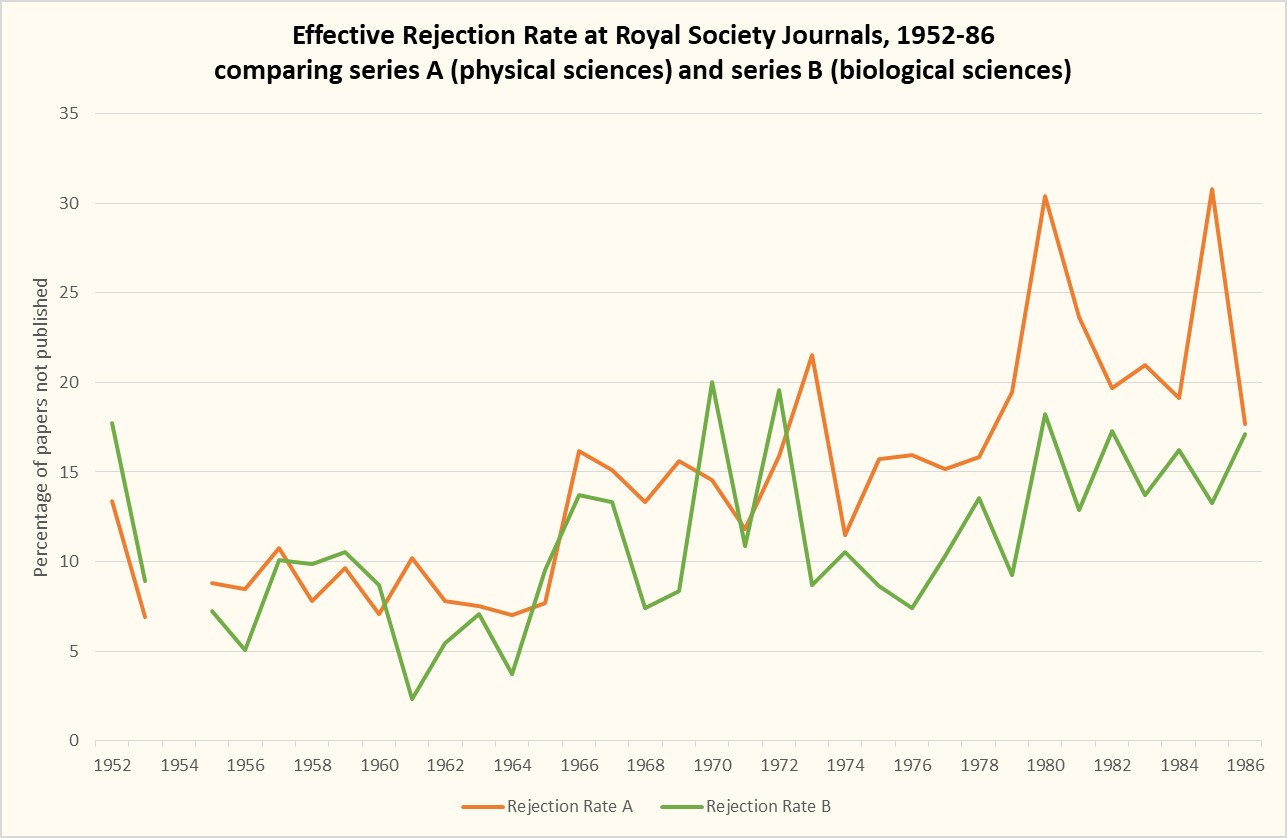

Rejection rates in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1950s-1980s

This graph offers additional detail on the overall rejection rates at the Royal Society’s Transactions and Proceedings in the second half of the twentieth century. As I discussed in that earlier post, the Royal Society historically had a low rejection rate (around 10-15%), due to the filtering-out of papers that was done pre-submission, since papers had to be submitted via a fellow. Continue reading “Rejection rates in life sciences vs physical sciences, 1950s-1980s”

More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s

I looked at the numbers of submissions to the Royal Society journals in an earlier post. Here, we look at the relationship between the number of submissions, the rejection rate and the sustainability of peer review. Continue reading “More submissions, more rejections: the Royal Society Journals since the 1950s”

Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time

The Royal Society has been asking for expert advice on papers submitted for publication since the 1830s, and quality (or something like it) has always been one of the elements under consideration. Here, I investigate how the definition of ‘quality in peer review’ has changed over time.

Continue reading “Quality in peer review: a view through the lens of time”

What the history of copyright in academic publishing tells us about Open Research

The protections offered by copyright have enabled authors – and their publishers – to make a living from their works since the first copyright act, for ‘the Encouragement of Learning’, was passed in 1710.

Academic authors, however, do not depend upon copyright for their livelihoods. Instead, for many researchers, copyright has come to seem like a tool used by publishers to pursue commercial, rather than scientific interests. Notably, open access advocates have long argued for changes to the ways researchers use copyright, a position that has recently found support in Plan S’ mandate for the use of Creative Commons licences as an alternative.

Continue reading “What the history of copyright in academic publishing tells us about Open Research”