For most of its 350 years of existence, the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions had no named editor. Only in the late twentieth century were editorial positions assigned. Yet, throughout its long history the Transactions was almost always managed by one or more of the Secretaries to the Society. As the ‘advertisement’ in Transactions for 1752 stated: ‘the printing of them [Transactions] was always, from time to time, the single act of the respective Secretaries’ (Phil Trans 1751, 47, Advertisement, unpagenated). This tradition started with Henry Oldenburg, who was Secretary in 1665 when he produced the first issue of the Transactions. Oldenburg was the proprietor and editor, paying for the Transactions from his own pocket. After him, his successive secretaries carried on the tradition of the running the Transactions, without direct financial support from the Society, although often operating out of the Society’s rooms and receiving an honorarium as Secretary. Only after 1752 did the Society take official responsibility for the Transactions. The Society was facing criticism over its running and contents, despite not being officially associated with it. The decision was made to claim ownership in order to control it more directly. Secretaries continued to take charge of the journal, despite there being little direct instruction to. The definition of the secretaries’ duties in the statutes of the Society focused on arranging and keeping the records for Society meetings, and dealing with its correspondence, with just a brief mention of ‘the charge (under the direction of the Committee of Papers) of printing the Philosophical Transactions and correcting the press’ (Record of the Royal Society, 194?, Statutes for 1847, p.??). One of the most influential, in addition to Oldenburg in the seventeenth century, was Charles Blagden, who worked closely with the President, Joseph Banks, in preparing the Transactions in the eighteenth century. Presidents had varying degrees of involvement, but by the mid nineteenth century they rarely took much interest in publishing, except by default as members of the Committee of Papers. Another important secretary-editor was physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes, who was Secretary for thirty-one years in the mid to late nineteenth century. During this time he moulded refereeing into a process that involved revision, rather than simply using it as a way to protect the Society from claims of unfair practice. Stokes was close to a named editor, calling himself the ‘editor of the Transactions’. Yet, he still operated within the Society’s collective editing model; the Committee of Papers still had to be consulted on publishing decisions.

1925: Printed referee report forms (used since the 1890s)

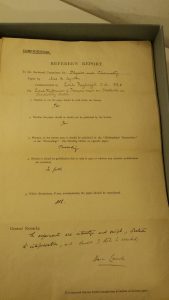

In the 1890s, the Royal Society had introduced a set of 7 questions for referees, in the hope of structuring the reports (which were sometimes extremely long-winded!). These were originally hand-written into the covering letter, but were quickly turned into a printed standardised report form, sent to each referee with the manuscript to be evaluated. Referees were encouraged to return their reports within 14 days – a deadline that was routinely breached.

By the early twentieth century, these report forms included clear instructions for referees, including advising them of the confidentiality attached to the papers referred to them (see image). It was routine for the author’s name to be written on the form: refereeing was single-blind, not double-blind. At this time referees were always Fellows of the Society (and their names and reports were kept confidential), but the majority of papers came from those outside the Fellowship.

The report forms made it possible for a referee to present an extremely succinct report, as was the case with Professor H. Lamb’s report on this 1925 paper by ‘Mrs. H. Ayrton’. Hertha Ayrton’s work in electrical engineering had previously been published with and exibited to the Society, but her status as a married woman had prevented the Royal Society accepting a fellowship nomination certificate in her name in 1902. (Her husband was also a well-known electrical engineer, and Fellow of the Royal Society, William Ayrton.)

The printed forms were also an attempt to standardize the refereeing process, or to at least advise referees on how to write an effective report. The Society never officially instructed referees until this date; referees were automatically expected to know how to write a report. Guidance on this continued to develop. By 1926, ‘Instructions to Referees’ was part of the Society’s Standing Orders.

Source: Box RR, 1925-1926, Royal Society Archives, London.

1895: Creation of Sectional Committees

By the end of the nineteenth century the Society was facing the challenge of increasing specialization in Science, as well as the continued growth in the submission of papers to its publications. The combination led the Society to reconsider the way it managed the selection of papers. The result was the creation of individual committees, with around 10 Fellows who had expert knowledge in a particular area of science. These were called Sectional Committees; they were each led by a chairman. They consisted of the Mathematical, Physics and Chemistry, Zoology, Geology, Botany, and Physiology committees. Now, instead of papers being sent on receipt directly to referees or to the Committee of Papers, they were sent to the relevant Sectional Committee, whose members administered their refereeing, before sending a summarized report and provisional decision to the Committee of Papers. In reality, the Sectional Committees met infrequently, decisions on papers were often made through correspondence. What was important here was that the administering of refereeing was no longer simply down to the Secretary and the Committee of Papers as a whole. The creation of the Sectional Committees was to reduce the burden of work the Council faced, and to lessen the work carried out by the Secretary, who took on a lot of editorial work. There was thus a decentralisation of editing, which meant that it was now the Chairmen of the Sectional Committees, along with the Secretary, who were central to the Society’s management of its editorial practices until the decommissioning of these Committees in 1868.

Source: CMP/7, 21 February 1895, p. 146-150, Royal Society Archives, London.

Printed referee report form (used since the 1890s)

In the 1890s, the Royal Society had introduced a set of 7 questions for referees, in the hope of structuring the reports (which were sometimes extremely long-winded!). These were originally hand-written into the covering letter, but were quickly turned into a printed standardised report form, sent to each referee with the manuscript to be evaluated. Referees were encouraged to return their reports within 14 days – a deadline that was routinely breached.

By the early twentieth century, these report forms included clear instructions for referees, including advising them of the confidentiality attached to the papers referred to them (see image). It was routine for the author’s name to be written on the form: refereeing was single-blind, not double-blind. At this time referees were always Fellows of the Society (and their names and reports were kept confidential), but the majority of papers came from those outside the Fellowship.

The report forms made it possible for a referee to present an extremely succinct report, as was the case with Professor H. Lamb’s report on this 1925 paper by ‘Mrs. H. Ayrton’. Hertha Ayrton’s work in electrical engineering had previously been published with and exibited to the Society, but her status as a married woman had prevented the Royal Society accepting a fellowship nomination certificate in her name in 1902. (Her husband was also a well-known electrical engineer, and Fellow of the Royal Society, William Ayrton.)

The printed forms were also an attempt to standardize the refereeing process, or to at least advise referees on how to write an effective report. The Society never officially instructed referees until this date; referees were automatically expected to know how to write a report. Guidance on this continued to develop. By 1926, ‘Instructions to Referees’ was part of the Society’s Standing Orders.

Women and the History of Peer Review at the Royal Society

Following the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919, the Royal Society nominated and elected its first female Fellows in 1945. But long before this female authors had published in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions and the Proceedings. There had been a steady, small trickle of female authors since the 1890s. They would often publish with husbands or colleagues, but there was also a noticeable group of solo female authors, often tied to the early women’s right movement.

Until 1990 (there was a brief experiment in 1974), authors needed to go through a fellow in order to have their paper officially communicated, reviewed and published at the Society. The official role of a communicator was thus held only by men for most of the Society’s history. By the 1960s crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale and biochemist Dorothy Hodgkin were the most active female referees and occasional communicators of papers at the Society, having been elected to the Fellowship in 1945 and 1947 respectively, and having since been joined by almost 200 other women.

Despite this expansion, male referees sometimes included their personal opinions about female authors in their referee reports. Some female authors were cautioned against being ‘too ambitious’, or for using ‘emotional’ language. The private lives and marriage status of female authors were sometimes discussed too, not in terms of who they published with, but whether they would stay in the field after starting a family. Comments like these would be cut and pasted by the Secretary and then sent to authors, so that they did not see the original report or such remarks. Although opinions such as these were of their time, comments about female author’s work would sometimes be judged along these lines until the 1980s, when the referee reports became more formalized and professional in tone.

Despite this, sexism in referee reports only occurred in a small number of cases. On a whole, men and women reviewed each other with great respect, often adding pages of extra comments to help the author get their manuscript out. This collegiate tone is reflected in referee reports throughout the twentieth and twenty-first century at the Society. This, along with increasing gender diversity in journal editorial committees, makes the comments about ambition and gender in the past all the more disappointing.

There are still firsts’ happening at the Society in modern decades. Professor Georgina Mace (above, right) and Dame Professor Linda Patridge (above, left) became the first female editors of any Society journal in the 2010s (both of Philosophical Transactions B) and the first female Head of Publishing is on her way in in 2017.

Follow us on Twitter at @ahrcphiltrans for updates on this topic. We are currently collecting all our gender material for a longer paper about the history of women and publishing at the Royal Society. There’s a lot more to say; – get in touch if you have things to add!