What does peer review do? Every academic author nowadays is used to the process of receiving reports on their submitted manuscripts from independent experts consulted by the editor of the journal. Refereeing undoubtedly delays the publication of research, but it is widely believed to add significant value as a means of accrediting ‘proper’ research and researchers.

Amidst all the current discussions of the future of academic publishing, there lurks a strangely ahistorical view of the academic journal. It is not uncommon to hear that the peer-reviewed research journal has been at the heart of the scientific (and, by implication, scholarly) enterprise since the beginnings of modern science. But our research reveals that there is nothing natural, inevitable or timeless about the way academic research is published.

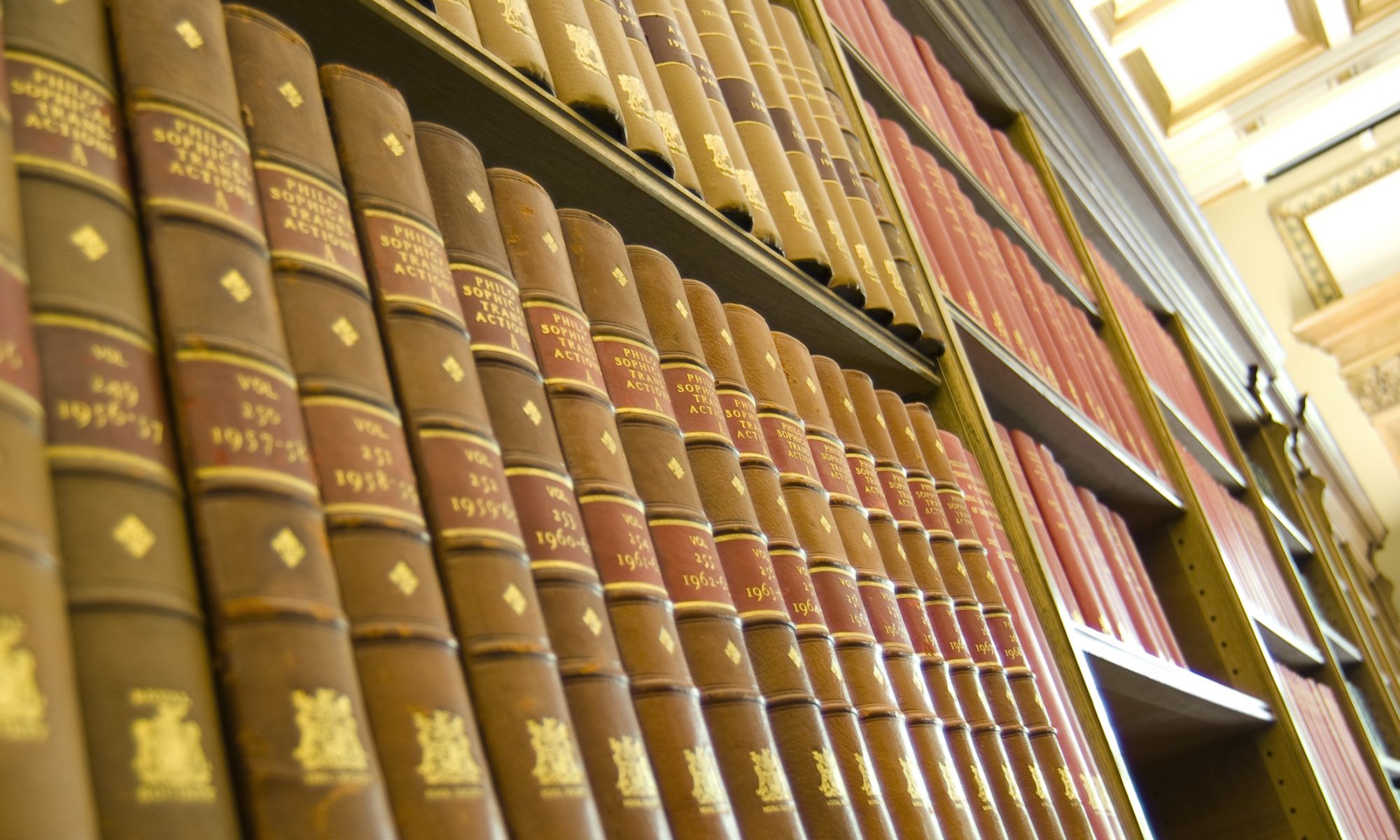

We have spent the last five years studying the history of the Philosophical Transactions, the world’s longest-running scientific journal. From the start, it was associated with the Royal Society of London, and the association was formalised in 1752. This is good news for the historian, because the Royal Society is the sort of institution that takes care to keep its own records (and, nowadays, to digitise some of them). We were able to use these archives to investigate the claims for a seventeenth-century origin for peer review (which we do not believe are helpful in any meaningful way), and to examine the emergence of editorial practices that more closely resemble our own, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One can argue about how to define peer review, but it is apparent that the Royal Society began using written refereeing in the 1830s (and there is evidence that other learned societies in Britain were doing similar things around the same time, as Alex Csiszar discusses in Ch. 3 of his new book The Scientific Journal, 2018).

Our research shows that the modern association between refereeing and ‘quality control’ did not emerge until the mid-twentieth century. Back in the nineteenth century, refereeing had rather different social and epistemological functions, grounded in its role as one element in a complex editorial system that created the impression of collective decision-making by a community of scholars.

From the perspective of the Royal Society as a corporate body, collective editorial responsibility was a way of reducing the reputational and financial risk of poor decisions. By the beginning of the twentieth century, when the cost of publishing so many scientific papers was becoming overwhelming, referees became stewards of the Society’s finances, specifically tasked to decide whether there was sufficient intellectual justification for so many pages and illustrations. (This was something they were not actually very good at!)

For scientific authors, the refereeing process in the nineteenth century did not usually suggest significant revisions (to lengthy handwritten manuscripts!), but referees did point out logical flaws or errors of fact, and they were likely to comment on inadequate acknowledgement of the work of previous scholars. What is fascinating is that, no matter how often the Royal Society formally denied that publication in its journals was any guarantee of the truth or certainty of the research, successfully navigating its convoluted editorial processes became a badge of prestige for authors.

Thus, publication in learned society journals came to carry significant weight in the reward and recognition systems of early twentieth-century British academia. All of us who submit articles to scholarly journals are working with that legacy.

[This essay was written to accompany our article The Royal Society and the Prehistory of Peer Review, 1665–1965 by Noah Moxham and Aileen Fyfe published in The Historical Journal 2018. It originally appeared on the Cambridge Core Blog on 9 Nov. 2018].

[The full research article is available OA as an AAM ]

” That The Philosophical Transactions to be composed by Mr.Oldenburg , be printed the first Monday of every month, if we have sufficient matter for it and that the tract be licensed by the Council, being first reviewed by some members of the same”.

Isn’t this found in the first issue of Phil Trans ? That would show that it was the first to implement peer review although Le Journal des Sçavans was founde two months earlier.

That entry from the minutes of the Royal Society Council is often quoted, but it doesn’t actually demonstrate that peer review was being used in 1665. For a detailed explanation, do read the first sections of the journal article that this blog refers to (https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X17000334). The simple version goes:

a) the ‘review’ that was theoretically to be undertaken by ‘some members’ of Council was part of the system of political and religions censorship (licensing for publication) that was in operation in 1660s England. It was not a review to investigate scientific rigour, logical argument or the replicability of the experiments or observations. i.e. it was not academic peer review.

b) We’ve looked closely for evidence about what actually happened each month (rather than what was supposed to happen), and have found that even this political/religious ‘review’ didn’t always happen, or when it did, it just involved the president asking the editor what the contents of the next issue would be. There’s no evidence of multiple members of Council being involved; nor of the president actually looking at the contents.

So, while I understand why people might think this is evidence for peer review in 1665, it actually isn’t.

As for when ‘peer review’ did start, it depends which aspect you think is most important: do you mean ‘more people – not just the editor – were involved in making editorial decisions’, or ‘people with subject-specific expertise were involved in making editorial decisions’, or ‘people with subject-specific expertise had to read the full-text of the paper carefully, and write a report on its suitability’? Depending on your answer, then peer review at the Royal Society started sometime between the 1750s and the 1830s. If you’re interested, do read our paper!