The history of the Royal Society’s publications in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, has been one of immense fiscal growth.[2] From a publication system that did not concern itself much with the finances of its journals, the Society is today concerned with optimizing its “products.”[3] Like the histories of so many scholarly journals in these decades, the Society’s journey from benevolent publisher to professionalised semi-commercial status has followed the pace and direction set by commercial publishers in the West. It is a history of changing ideologies and perspectives, of experiments and risk-taking, but it is also a story of exploring public engagement through publishing. Today, the Royal Society actively tweets and emails about its published material, ensuring large coverage in the mainstream media. But it was before this time, that the seeds of its modern interest in communicating with the public were sown through the experiment that was Science and Public Affairs, a journal with direct support from COPUS. In this essay I explore the behind-the-scenes story of the journal, edited by Sir Walter Bodmer, which became a magazine.

A new journal and a makeover

As the Society explored commercial ventures in the late 1990s, it had yet to start competing by way of creating new products. This became a problem in the late-twentieth century, as commercial publishers flooded the market with exactly this.[4] The last time the Society had created new publications had been in the 1930s, first with the Biographical Memoirs of the Fellows of the Royal Society (containing mostly obituaries and annually published) in 1932, and the science historical journal Notes and Records in 1938 (containing mostly history about the Society and its fellows). Both were aimed at the fellowship, and did not carry scientific content. As the millennium approached the Society became more interested in competition, and started to explore new product avenues. Like before, it did so with a non-scientific journal, but this time it was aimed towards the general public and policy-makers. The first new product to be created since the 1930s was Science and Public Affairs (SPA) in the mid-eighties. At first SPA was a depositary-style journal for material that did not go into the Society’s other journals for various reasons, and was published jointly with the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS; British Science Association since 2009). Its first editor was Bodmer, who had chaired the committee that wrote the Royal Society report “The Public Understanding of Science” (sometimes known as the Bodmer report) in 1985.[5] At the time, a committee that was semi-independent from the Society’s Council, the Publications Management Committee (PMC), oversaw the general development and finances of all the institution’s journals, whereas a dedicated SPA editorial committee met to discuss the future of the journal. It was in the years between 1985 and 1990 that the Society decided to revamp all of its published journals, including editorial processes, finances, staff, and the visual look of each volume. As part of this makeover, it was suggested that SPA could perhaps take on a new role, from small depository journal to glossy magazine for the educated masses.

Not the the New Scientist

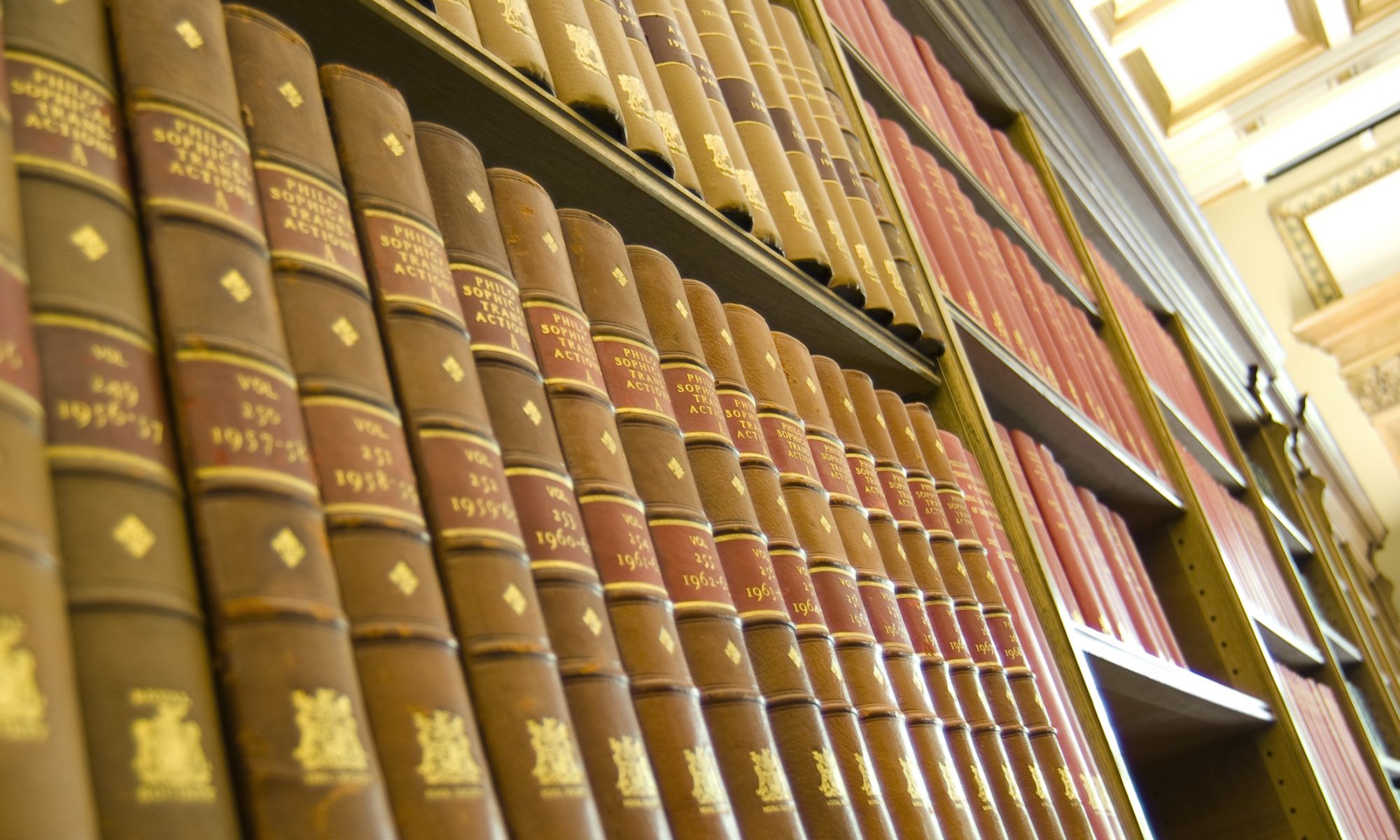

The PMC envisaged the new SPA as a widely available publication, possibly even sold through newsagents, a first for any Society publication. Older society publications dated back to the 17th century, when the flagship publication the Philosophical Transactions was first published. Since then, the Transactions had been joined by the shorter-format Proceedings. However, both publications were distinctly research-focused, and developed for and read by academics. The Society had seldom before been concerned with public engagement by way of journal or magazine publishing, which makes the case of SPA so unusual, and possibly is also an explanation for its short-lived status. During discussion of what would become the makeover of SPA, the Publications Management Committee at the Society emphasised “that the intention was not the popularization of science in the sense of New Scientist, but that the journal should be seen more as a quarterly (or, eventually, monthly) review of science, with the emphasis on public affairs.”[6] One slightly sceptical member of the committee stressed the need for impartial factual articles, not based on opinion, for the benefit of major decision-makers. In other words, the Society was willing to take some risks, but not go totally ‘pop’ like the popular science magazines tended to.

Diversity

On a whole, Bodmer accepted the Society’ directions by way of the PMC, but he also sought a lively style to attract readers and did not want to create a house-journal for the Society, which would perhaps have been a more traditional route to take.[7] An eclectic mix of science reviews, policy news, illustrations, glossy photographs, and entertainment followed. In one issue of SPA we can see the diversity on offer in terms of content. Cosmologist (and, later, President of the Royal Society from 2005 till 2010) Sir Martin Rees asked why the media gave a distorted view of science in the editorial, writing: “the media, understandably, tend to highlight the human angle, the politics and the gee-whizz factor.”[8] A mid-career Richard Dawkins was interviewed about the role of philosophy in the selfish gene doctrine. The article “Snap, Crack and Pop” examined “good vibrations from joints” (not of the herbal kind). Two reporters were sent out to explore what happened when 400 children hijacked the Science Museum for a night (chaos, laughter and learning). The issue was crowned by a “COPUS crossword-puzzle.” Except for Lorraine Ward (on the children piece), all the reporters, authors and journalists were male. But the editorial committee of fifteen people included one woman, Ms W. Barnaby, and ten of the twenty-one commissioning editors where female. Published quarterly and priced at £5.25 (or £20 annually) it was the Society’s most gender-balanced, cheap and accessible journal ever.

Science journalism in a learned society

The decision to give SPA a makeover and keep the tone engaging subsequently attracted a new type of editorial assistant to the journal.[9] From a role mainly to do with chasing other people’s work and deadlines, editorial concerns, working with Bodmer, and copy-editing, the editorial assistants whom worked on SPA when it became a magazine often wanted to be or become science journalists. One individual went on to work at the New Scientist, but all disappeared out of the role within two-to-three years. Bodmer remained, working with his enthusiastic editorial assistant to produce an interesting magazine for the lay reader. The only problem was that the editorial assistants also had the responsibility of all of the Society’s other non-scientific and occasional publications. Amongst these were two continuous publications of very different natures; the Biographical Memoirs and the Notes and Records of the Royal Society. The everyday work for each of these outputs thus fell to one person, who more often than not was more drawn to the glamour and contemporary feel of SPA, than the heavy, traditional and institutional nature of the other products. Furthermore, SPA was for sale everywhere (made possible by subsidized finances), whereas the Biographical Memoirs and Notes and Records were aimed towards the fellowship and their interests. For ambitious science journalists, the popular and diverse SPA became an exciting stepping-stone to a writing career.

The end of the Society connection

As SPA continued to circulate and be distributed amongst varied groups interested in scientific news and politics, it garnered more approval from its paternal keeper. In 1991, the responsibility for SPA transferred from the Society’s Publications Management Committee to its own management group, one in a series of steps towards making the magazine more independent.[10] By 1995, the Society and BAAS did some consumer-testing on their magazine, and found that SPA was indeed “highly regarded by recipients”[11]. An impressive 40% of the Society’s own fellowship opted to take SPA in lieu of the traditional journals, Proceedings and Philosophical Transactions.[12] Despite this, the Society was concerned for a number of reasons. Since 1985, the scholarly publishing field had changed enormously, and the Society was now getting serious about acquiring more surplus through its subscription models in line with what commercial publishers were already doing elsewhere. Furthermore, magazine publishing was deemed to be a different world to journal publishing, one in which outfits like Nature and New Scientists were sweeping the market, and becoming competitive on a completely different and unattainable level. Finally, the subsidizing model of SPA was no longer viable and the magazine was defined by the Royal Society to be popular, but too expensive. Worries about finances were thus frontline and centre when the Society decided to let SPA go in the mid-nineties.[13] It was suggested that BAAS could take over SPA entirely, which it did, and the Society has since focused its policy work on more traditional policy papers and public engagement.[14] Responsibility for SPA transferred from the Society to BAAS on four conditions: the journal should be collaborative publication with BAAS, a sponsor should be found to pay for 1,000 free copies, COPUS should agree to provide £10,000 toward the publishing costs for the first year of the new-style publication, and that the design changes should be made by 1992.[15] BAAS and COPUS agreed, and the move was made. Since, the journal changed shape and tone again, but never quite regained the diversity of content it had displayed while run by the Society, BAAS and Bodmer together.

Conclusion

The small decade in which the Royal Society published SPA can tell us something unique about the moment in time when COPUS had a genuine impact on British science. In the eighties, the Royal Society was, and some would argue still is, a traditional boy’s club affair based on tradition, hierarchy and reputation. It was vital in the COPUS movement, as were many of its fellows, but SPA reveals a playful side to the elite institution only made possible by the decades flirtation with the possibility of making science sexy. SPA carried quizzes, interviews and science journalism, and was sold to a wide market in newsstands. Furthermore, it made little to no money for the Society or BAAS, yet was kept going out of what seems to be sheer enthusiasm. Most scholars of publishing or the Royal Society may agree that that moment has now passed. Nothing has been published at the Royal Society without a secure financial plan in place first since the mid-nineties. In fact, publishing is today one of the top sources of surplus for the institution, even as the profit-driven model of scholarly communication is being debated in wider academic communities. Furthermore, the moment in time where the Society published science journalism can also be said to have passed, as policy work and other public engagement projects rooted in education has taken over. The sense of fun that SPA brought with it, however, is not completely gone. Today, the Society’s YouTube channel ‘Objectivity’ showcases popular videos of treasures from the institution’s archive, and children often visit the building for a range of events (chaos, laughter and learning). The legacy of SPA can best be seen in science journalism, and although we may mourn the decade where the Society genuinely wanted to connect to the lay-reader through a magazine, I think we can all agree to be glad that the time of COPUS-crossword puzzles is gone.

Notes

[1] School of History, University of St Andrews, UK.

[2] This paper is based on research from the AHRC-funded project ’Publishing the Philosophical Transactions ’ at the University of Manchester. Project website (with forthcoming information about publications and data sets): https://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/philosophicaltransactions/ (Accessed 4 April 2017).

[3] Journals start to be described in these words in the late nineties. Meeting of the publishing board (14 January 1998), PUB/10 in Royal Society Publishing Board minutes (1996-2015), box CMB/417, Royal Society archives.

[4] Derek J. de Solla Price, in his landmark study on the growth of scientific publishing, estimated an exponential growth rate of about 5.6% and a doubling time of thirteen years from the 1950s. D.J. De Solla Price, Science since Babylon (Yale University Press, 1975).

[5] A COPUS grant scheme was set up in 1987, funded by the Office of Science and Technology and the Royal Society, with the last rounds of grants in 2003/4 (25 grants were awarded). COPUS was discontinued in 2002.

[6] Publications Management Committee minutes (28 November 1989), file C/230 (89), box PMC/26(89), Royal Society archives.

[7] PMC meeting (16 May 1990), CMB/367.

[8] Martin Rees, ”The Big Picture”, Science and Public Affairs , Autumn 1994, p.3.

[9] Interview with Chris Purdon, former member of publishing staff at the Society, by Røstvik, via Skype, 12 April 2017.

[10] Publication Management Committee meeting (20 June 1991), box CMB/367, Royal Society archives.

[11] The Royal Society Publication Review Group, final report, p. 9, folder C/31(95), Royal Society archives.

[12] Publication Management Committee meeting (28 November 1989), file C/230 (89) in box PMC/26(89), Royal Society archives.

[13] Publications Management Committee minutes (28 November 1990), file C/214(90), box PMC/29(90), Royal Society archives.

[14] The Royal Society’s Policy webpages: https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/ (Accessed 26 January 2017).

[15] Publications Management Committee minutes: 20 June 1991, file C/123(91), box PMC/32(91), Royal Society archives.