[This post by Anna Gielas first appeared on TheStudentBlog at PLOS on 14 June 2016]

“Academic publishers make Murdoch look like a socialist”. This is the title of a Guardian opinion piece from 2011– and it is hardly the strongest critique of the academic publishing industry. Academic publishing tends to stir up controversy within scholarly and scientific communities. Sometimes it provokes individuals, like graduate student Alexandra Elbakyan, to take matters into their own hands. Elbakyan created Sci-Hub, a database of pirated academic articles, and is now facing charges for copyright infringement.

This lawsuit has fueled more discussion about how to change and improve upon the current publishing system. An example of a common argument from critics is that the current publishing system pressures academics into hastily publishing novel, attention-garnering studies instead of working toward lasting contributions to scientific and scholarly knowledge. Misconduct such as data falsification is but one of the worrying consequences of the ‘publish or perish’ climate in modern research. In turn, universities and libraries face financial barriers that stem from expensive publishing costs and high subscription rates.

Proponents of the status quo maintain that traditional academic publishers such as Elsevier, Springer,Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, and Taylor & Francis shield academics from “predatory” journals whose numbers have increased throughout the last years. The phrase “predatory” refers to publishers that charge the scientists expensive fees to publish their research in a particular journal without providing the usual services such as peer review and extensive editing services, among other things.

Coming together to examine (overlooked) challenges in publishing

Recently, an interdisciplinary group of scholars, publishing executives, and education researchers convened at the Royal Society of London to look beyond the common critiques of academic publishing and also examine lesser-known issues. The group discussed past and present structures of scholarly publishing—as well as their roots and broader implications, and I was able to attend the event.

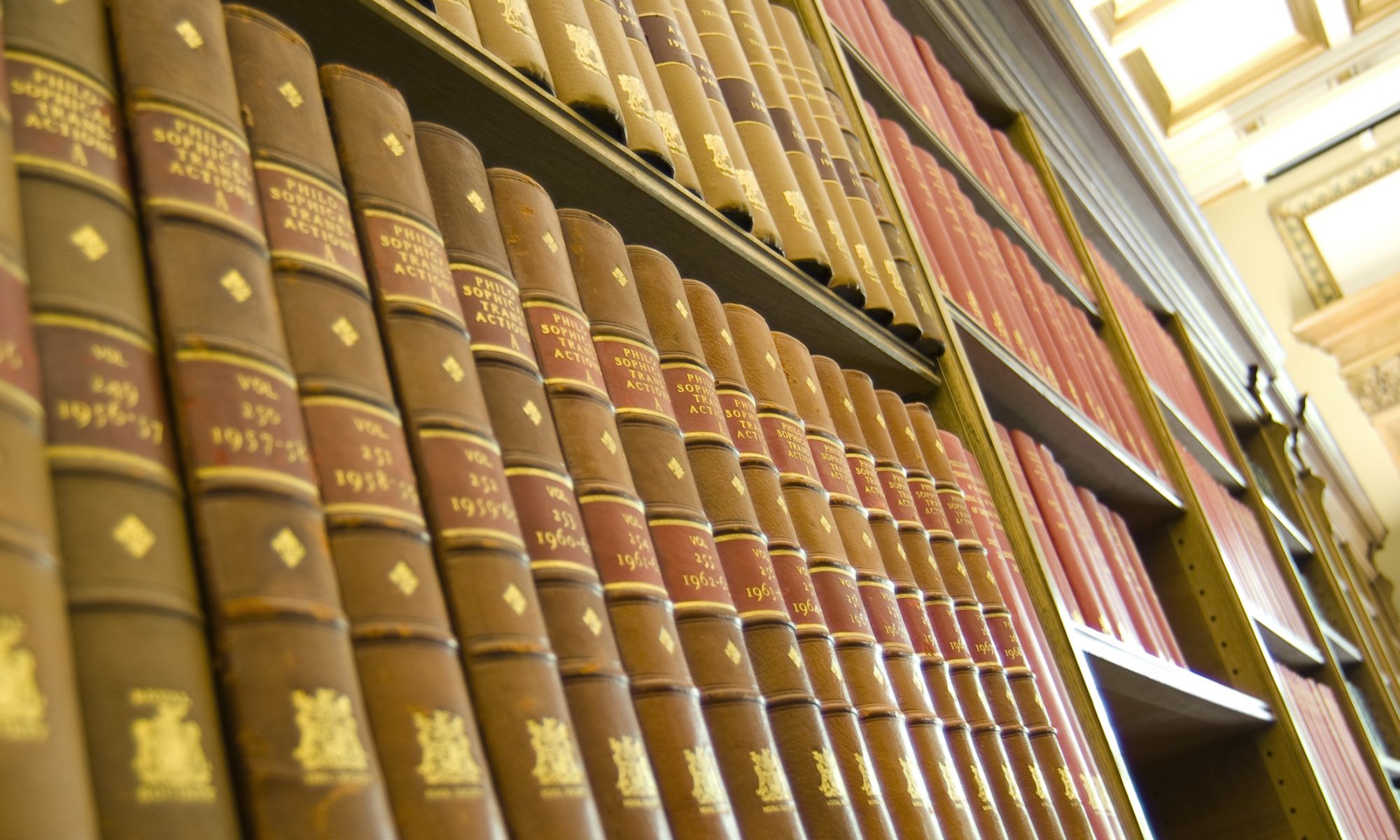

“The Politics of Academic Publishing, 1950-2016” workshop was organized by the ‘Publishing the Philosophical Transactions’ project at the University of St. Andrews, and was led by Aileen Fyfe, Camilla Mørk Røstvik and Noah Moxham. The workshop’s comprehensive review of the history of academic publishing allowed the group to take a step back and gain a sense of how academic publishing has changed in the last six decades. The present situation became a point of reference for the participants to ask what academic publishing has gained and lost over the last 66 years.

The spread of academic publishing over time

Jack Meadows (Loughborough University) kicked off proceedings by placing the expansion of learned publishing in the 1950s in the context of the scientific race between the East and West. He used thePergamon Press as an example of how the global race for scientific innovation fueled publishing. Twelve years after its commencement in 1948, the Oxford-based publisher hosted 40 academic journals. Ten years later, Pergamon Press had expanded even further to include 150 .

Stefan Collini (Cambridge University) examined academic publishing in the 1960s and 1970s, stating: “Universities were much less in the business of justifying themselves to the self-appointed representatives of the public interest, and scholarship was seen as something that chiefly concerned other scholars.” Collini mentioned well-respected academics from the 1960s and 1970s who published their first monograph years after they were tenured and managed to gain renown despite having less than a handful of journal articles to their name. This presents a stark contrast to today’s situation in which article publications are a crucial means for furthering and sustaining one’s career.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the academic journal still struggled to make a profit. Publishers had to rely on other ways to finance their academic activities—such as the textbook market in former African colonies, as Caroline Davis (Oxford International Centre for Publishing Studies) explained. “In the book trade – both in Britain and in many of its former colonies – the structures and hierarchies of imperialism long survived the demise of colonial rule itself,” said Davis. “After decolonization, British academic publishers continued to regard book markets in former colonies as their prerogative.”

Davis pointed out that British publishers have undermined the establishment of African ones. “Some people view this as a reason for today’s South-North-gap in academic publishing,” she concluded. The lack of highly regarded African journals is just one of the current challenges in academic publishing that tends to be overlooked, but was brought up by the interdisciplinary group.

Academics encounter gender-based hurdles to publishing

Kelly Coate (Director of King’s Learning Institute) turned the audience’s attention to another problem, namely the obstacles that female academics face in the academic publishing world. “Women encounter notably more implicit and explicit biases (to publishing),” Coate said. She said male academics, for example, tend to cite each other—and much less their female peers.

Camilla Mørk Røstvik, who studies the editorial archives of the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, reported that female researchers in the 1950s faced similar prejudices toward their work. “The first names of male authors were usually initialed. But articles written by female researchers included the women’s full first names, suggesting essential differences in studies conducted by women and men,” Mørk Røstvik said.

Despite facing gender-based prejudices, female scientists acted as peer reviewers throughout the 1950s. While doing so, “they were generally – and knowingly – addressed as “Sir””, Mørk Røstvik added.

Though publishing has improved for female scientists since the 1950s, decades of gender bias and inequality remain deeply ingrained in the infrastructure of academic publishing. “Women themselves are influenced by implicit biases—which make them just as likely as men to make biased judgments that favor their male peers,” Coate said.

How to improve academic publishing

What can be done to address systemic gender disparities in academic publishing? Workshop participants discussed the double- and single-blind models of peer review as one of the means to actively counter the problem. The French sociologist Didier Torny (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique) explained that these reviewing strategies have been discussed and shaped from the 1950s onward. But, Torny added, the terms were adapted from the mid-1980s clinical trials vocabulary.

“If you see peer-review as making an article better, then retractions are terrible and demonstrate considerable problems with the system of reviewing,” Torny said, suggesting that post-publication peer review could be a better, more promising approach. “Readers become a community which works together to steer findings in the right direction—the audience is actively contributing to the production of knowledge.”

Sue Clegg (Higher Education Research at Leeds Metropolitan University) was also highly critical of the current peer review model. “This practice is inclined towards conservatism,” she said. “Criteria for journal inclusion are far from transparent—they are oftentimes very murky.”

Clegg also brought up gender biases and cautioned her audience to pay closer attention to questions of: (1) Who is most likely to become a peer-reviewer? (2) Who is most likely to be admitted to journal boards? Clegg agreed with Torny, and emphasized: “We should consider how we can reconfigure peer-review as a more open-community practice.”

Throughout the workshop one topic resurfaced several times: disciplinary differences. The participants agreed that journals play different roles in different fields. For example, while physicists make intense use of academic journals, scholars of economics more commonly publish working papers. In some fields, journal authors have to pay word-fee, while in others they do not. Therefore, initiatives to improve academic publishing should consider these disciplinary differences.

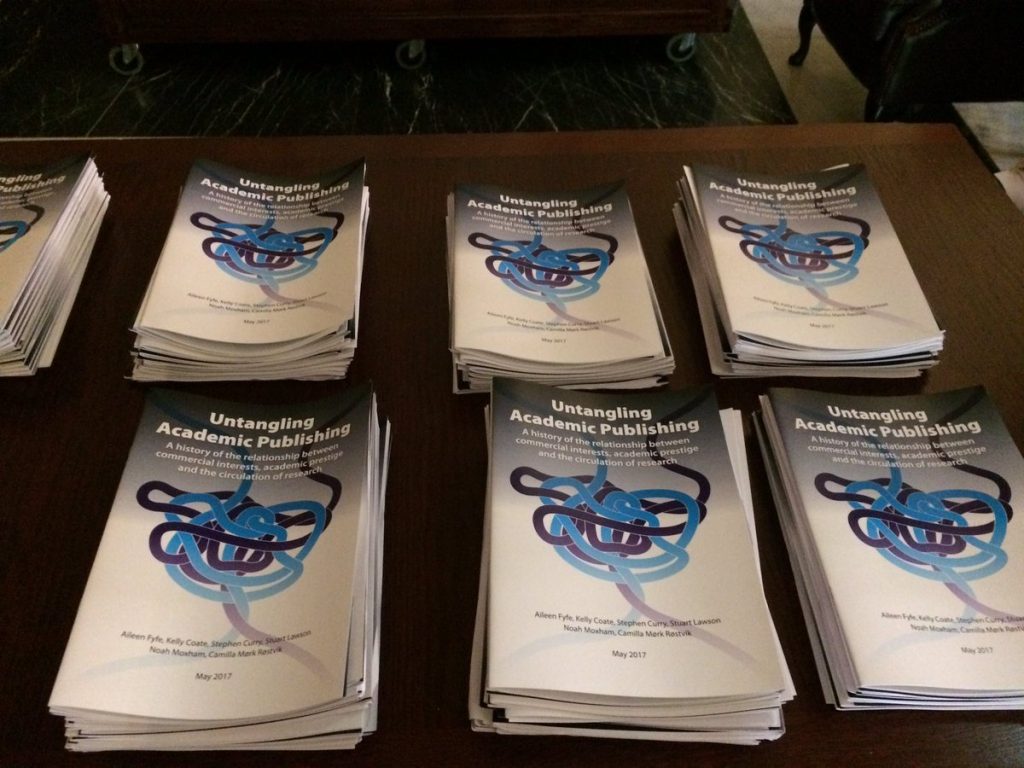

I felt this workshop was beneficial in that it looked beyond the usual catalogue of grievances and challenges in publishing. By applying a historical lens, the panelists were able to reflect new developments in academic publishing comparatively—and more critically. The lessons from history—as well as the disciplinary differences in academic publishing—will be key elements of the position paper that is currently being developed by the St. Andrews team.

Anna Gielas is a PhD Student in History of Science and Science Communication at the University of St Andrews

Aileen Fyfe was recently interviewed on the PLOScast about the history of scientific publishing.