The Visualising War podcast recently interviewed artist Jill Calder, author James Robertson and illustrator/book designer Jim Hutcheson, who is Creative Director at the Scottish publishing company Birlinn Books. They shared some fascinating insights into the representation of war, conflict and violence in children’s literature, based on the work they did together to create an illustrated history of Robert the Bruce, published in 2014.

We began by talking about the kinds of war stories which they had come across as children. While Jill was struck by the violence she encountered in some fairy tales, James and Jim remember enjoying comics like The Hotspur, The Eagle, Valiant and Commando War Stories in Pictures. All three mentioned the influence of films, particularly World War II films and Westerns; Zulu also got a special mention. For James, growing up in the 1960s and 70s, the Second World War still felt relatively recent – something which his parents’ generation had experienced first-hand – but he also recalls watching real-time footage of the Vietnam War alongside documentaries and dramas about more historic conflicts.

This got us thinking about the mix of fact and fiction which children are exposed to, and how fictional representations of war can enhance understanding of real or historic conflicts as well as vice versa. While James’ interest in the Wild West was sparked by comics and films, he followed it up by devouring history books on the subject. One of the books that made a huge impression on Jill as a child was Carve her Name with Pride, a dramatic retelling of the true story of agent Violette Szabo (later turned into a film), which widened Jill’s understanding of the different roles that women had played during WW2. Up to that point, Jill had only seen women playing a domestic role in representations of the Second World War.

We discussed the often unflinching representation of conflict in the encyclopaedias, history books, poetry collections and fairy tales which James, Jill and Jim grew up with. All three remember being both shocked and fascinated by particularly memorable images or descriptions of violence, from a black-and-white drawing of the beheading of Mary Queen of Scots to the description of the torture inflicted on Violetta Szabo in Carve her Name with Pride. Arguably, the stereotyping of villains and promotion of heroic ideals in the Commando comics (for example) tempered the impact of scenes of shooting, explosions and death, perhaps even desensitizing readers; but it was clear from what all three said that other representations of war and conflict had the power to make them stop and think, recoil, worry and evaluate the rights and wrongs of the story they had just come across.

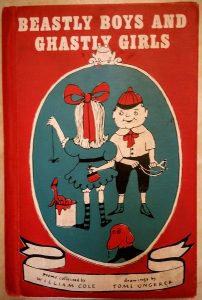

While some representations of war made a big impression on them as children, others have shocked them more in retrospect. Although comic, tongue-in-cheek and clearly unreal, the brutal interactions between parents and siblings in William Cole’s Beastly Boys and Ghastly Girls – brilliantly illustrated by Tomi Ungerer – are a useful reminder that our tolerance for different kinds of violence in storytelling changes over time. This got us thinking about what other changes we can trace in the representation of war and conflict in children’s books over the last few decades. We noted a widening of perspectives, moving away from a focus on adults, soldiers, models of heroism and fighting, to more exploration of the experiences of the wider population caught up in conflict, particularly families and children.

This is not a new phenomenon: two of the most compelling examples of a war story written from a child’s perspective are Ian Serraillier’s The Silver Sword (published in 1956) and Judith Kerr’s When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (published in 1971); of course the Diary of Anne Frank has also been seminal in shaping how both children and adults understand aspects of World War II and the Holocaust. The Second World War seems to have lent itself particularly well to storytelling from a child’s perspective: other examples include Carrie’s War (by Nina Bawden), Rose Blanche (by Ian McEwen, based on the work of Roberto Innocenti), Goodnight Mr Tom (Michelle Magorian), Once (Morris Gleitzman), The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (John Boyne)[i] and Number the Stars (Lois Lowry). While focused on experiences specific to their time and place (evacuation, the Blitz, Nazi occupation, and concentration camps), the young characters in these stories ask huge questions and make critiques of war that apply universally.

A related trend is the use of animals as a lens to look at war in children’s writing. Classic examples are Michael Morpurgo’s War Horse (1982) and Robert Westall’s Blitzcat (1989) – followed more recently by Jenny Robertson’s Wojtek: War Hero Bear (2014) and Miriam Halahmy’s The Emergency Zoo (2016), among others. Animals can be a particularly useful hook for younger children, a way of narrating conflict in accessible, thought-provoking and empathetic ways. Set in the Syrian civil war, the picture book The Cat Man of Aleppo by Karim Shamsi-Basha (2020) brings a true story to life, helping young readers grasp the terrible impacts of war while following a character whose compassion and kindness offer hope. Nikolai Popov’s wonderful book Why? features a frog and a mouse who get into a confrontation, sparked by jealousy, which turns into a full-scale war and ends up involving many of their friends. The absurdity of the characters and their behaviour helps children ponder the causes of conflict as well as its tendency to escalate and devastating consequences.

In some children’s books, adults offer role models – as well as models to avoid. Like Popov’s Why?, David McKee’s picture book The Conquerors plays with the absurd, featuring a cartoonish general bent on war who is baffled by people who don’t want to fight. By contrast, Jane Cutler’s The Cello of Mr O focuses on an elderly musician, whose cello playing brings solace to a community ravaged by war. In Michael Foreman’s A Child’s Garden, the focus is more on how a child might nurture new life and sow seeds of hope, even in a landscape devasted by war; and there is also sense that older generations are looking to younger ones with hope and expectation in Sami and the Time of the Troubles by Florence Parry Heide and Judith Heide Gilliland. That book captures how terrifying it is for a child to live in a war-torn city (in this case, Lebanon), but also how children find pockets of peace and ways to keep playing.[i]

Towards the end of our conversation, Jill, James and Jim discussed what future trends we might see as the children’s publishing world responds to new kinds of conflict, including drone warfare and cyber warfare. (You can find out what they said by listening to our podcast!) Whatever the future holds, it is clear that the war stories we come across as children profoundly shape our understanding of the nature, causes and consequences of conflict – and our responses to it. As Mandy Williams writes in this blog:

‘Images of violence and war are omnipresent. Fiction can help young people make sense of them. News images, fractured, decontextualized, leave a sense of hopelessness. A good plot, a context, the rhythm of a story unfolding can encourage exploration and questioning. Stories enable readers to identify with the protagonists, as real human beings with free will and self-determination, not as mere accidents of history. They transfer to the young reader a sense of their own agency.’

The question of what agency children are (or are not) given in representations of war in children’s literature is something which the Visualising War project plans to explore further. Many books place children at one end or another of the powerless/powerful spectrum, with some narratives characterising them as helpless victims in an adult world while others give (or load) them with the responsibility to rescue others or find life-saving solutions. Mandy Williams’ point, though, focuses on their agency not just as characters within a plot but as readers, interpreters, critics and questioners – and underlines the important role that children’s books and storytelling play in honing those skills.

As she notes, some people ask ‘Is war literature appropriate for children?’ Her answer? ‘Children love to play at being scared, and they like to hear readings of scary books. There is perhaps an evolutionary or psycho-protective drive to practice and to work through scenarios and emotions. As G.K.Chesterton told us, “Fairy tales do not tell children that dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed.” ’

This gets to the heart of what the Visualising War project is interested in: we study how war stories work, but also what they do to us. Some narratives of war reinforce problematic ideologies which can be leveraged to justify violence or drive others to conflict. Many representations of war in the world of children’s publishing operate very differently, however, as more positive interventions in an ongoing conversation about why people fight, what war does to people, and how to resist it. In other words, it is not only appropriate for children’s authors and illustrators to tackle the difficult topic of war; it is also important, because it can empower children to combat or ward off conflict (one of the dragons in our midst) through empathy, understanding, an awareness of its horrors but also a realisation that it can be stopped, not just survived.

The narration of historic conflicts is just as effective in this as contemporary or futuristic representations, as I discuss in Part 2 of this blog, where we dive into Jill, James and Jill’s depiction of the Battle of Bannockburn and other aspects of 14th century war and violence…

Alice König, 23.6.21

[i] Some controversy surrounds this book, due to its historical inaccuracies and misrepresentation of the harsh realities of life and death at Auschwitz (see, e.g., https://holocaustlearning.org.uk/latest/the-problem-with-the-boy-in-the-striped-pyjamas/). I am grateful to Rebecca Palmer for bringing this to my attention.

[i] Some further reflections on trends in the representation of war/conflict in children’s literature can be found here and here.