By Susan Werbe, dramaturg for the Great War Theatre Project: Messengers of a Bitter Truth, and co-librettist of Letters That You Will Not Get: Women’s Voices from the Great War. This blog was written to accompany a podcast episode featuring Letters That You Will Not Get.

How do we encounter and visualise World War I? It very much depends on who we are and in what country we live. Historian Jay Winter posits that World War I is the “forgotten war” in the United States. For the most part, history courses in high schools and universities examine the American Civil War, WWII, and the Vietnam War, but spend little time on the 20th century’s first global conflict, even as we continue to live with its outcomes in the 21st century.

We do meet WWI, however, through the arts and have done since the war ended. Film, in particular, most likely shapes our view of the war, and that view has been a very white, male, Eurocentric one. During the war’s centenary (2014-2018), several powerful films such as Journey’s End, War Horse, and 1917 took us to the Western Front as did Peter Jackson’s technically brilliant They Shall Not Grow Old, which used 100 hours of archival film footage, colorized it, and provided archival voiceovers from the war’s survivors. But whose voices, genders, experiences, race, and ethnicities were missing from the war’s history? How do we authentically represent this war, this global war, if these diverse voices are absent?

During the past decade, I have collaborated with artists from different disciplines – dance, theatre, and music – to create performance pieces that examine World War I through the lens of art. More specifically, to use men and women’s original writings from both sides of the conflict – letters, poetry, journals, memoirs, diaries, and novels – to form the centerpiece of each work. This use of original writings delivers an immediacy and rich authenticity in visualising the experience of the Great War.

In our earlier theatre work Messengers of a Bitter Truth, even though the creative teams and the performers connected to the projects were a diverse representation, the text remained Eurocentric. With the opera version of Letters That You Will Not Get: Women’s Voices from the Great War, however, we have been able to capture the greater truth of a global war and the urgency, hardship, and tragedy experienced by women across geographies and ethnicities.

Letters That You Will Not Get: Women’s Voices from the Great War is a chamber opera that gives voice to women’s war experiences. Letters was originally conceived and performed as a short song cycle. When Brooklyn-based American Opera Project (AOP) offered Letters composer Kirsten Volness, my co-librettist Kate Holland and me the opportunity to expand the song cycle into an opera, we were delighted. Not only would we able to include more text set to Kirsten’s powerful and sensitive compositions, but even more importantly, we were able to create a more fully global work that included not only white European and American women, but also Black American, Caribbean, Indian, and African women’s responses to the war. That diversity was also reflected in the artistic team.

Unlike a traditional opera with named characters, Letters uses the words of real women to create archetypes that represent women’s war experiences from many countries on both sides of the conflict, diverse ethnicities and social classes, and quite different views on the war.

Our introduction to the libretto describes some of the archetypes that appear in the opera:

Mothers

One who embraces the war, even after her only child is missing for months and then reported killed.

“Violet passed on news from George: he said that up ’til now it had all been the most glorious fun.”

Another persuaded her husband to allow their youngest son to follow his older brother into the army and he was killed shortly thereafter. “Where are my children now? What is left to their mother?”

Daughters

Young women who volunteered as VADs (Voluntary Aid Detachments were nurses’ assistants) in theatres of war or ambulance drivers, “Dear family, The devastated country is much more strange and fantastic on a sunny day.”

OR a daughter trying to explain to her father even as she understands his support for the war, she sees its horrible reality daily as a nursing sister. “I understand too well how strongly you feel about the fate of our fatherland. Only our patients, in their awful agony, yearn for one thing, peace – “

OR in the case of one young Punjabi girl who was too young to do anything but worry about her father. “Dear Father, this is Kishan Devi. We were really scared after receiving your letter…”

Wives

Women at home, waiting for their husbands to return alive – whole (physically and mentally), or at least returning home as opposed to dying. Some knit “Shining pins that dart and lick” almost frantically; others knit resignedly, almost bitterly, “I sit and sew – a useless task it seems.”

A working class woman who views the war as one more way her life will be upended by forces beyond her control. “My husband’s in Salonika/I wonder if he’s dead.”

Lovers and Friends and Sisters

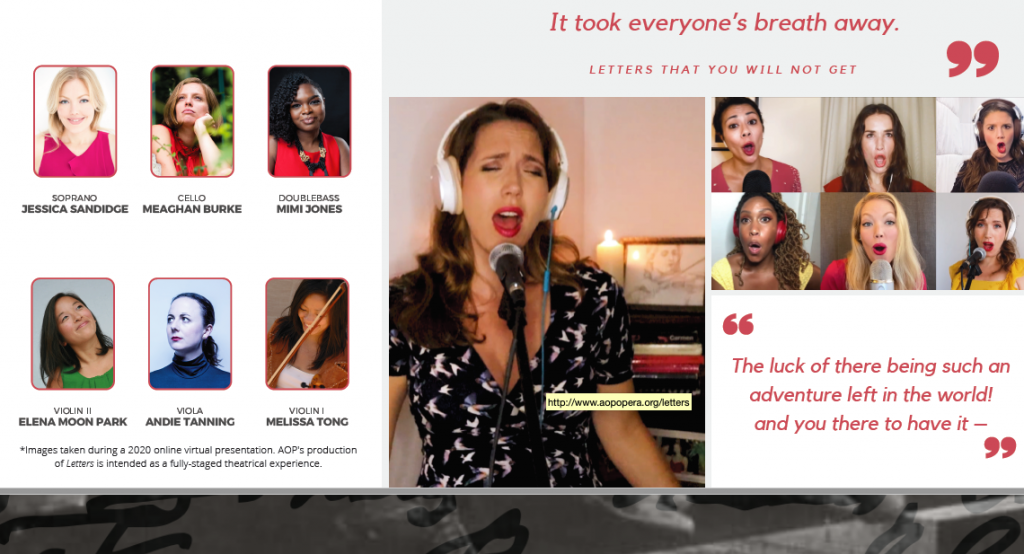

At the war’s beginning, expressing enthusiasm for a male friend’s volunteering, “The luck of there being such an adventure left in the world! And you there to have it – “

OR the young fiancée back home who has tired of waiting for her soldier to return, “My dear Jack, Everything must be over between us. Write back as soon as you can to say you forgive me Jack!”

OR women who lost their lovers, “When you lift up your eyes and cannot behold his face,/When your heart is far from him.”

Women of color

Women from Africa and India. Africa where men were taken into service by their imperial masters “At Karonga/People perished there, at Karonga./Why did they perish?”; India where women hoped the sacrifices made by Indian regiments would be rewarded by the end of the war by granting political self-determination. “Remember the blood of my martyred sons!”

Nurses

Women –experienced career nurses who if British nursed during the Boer War, or American nurses who came from US civilian hospitals. “If there is horror here you are not aware of it as horror. From the moment the doors close behind you, you are in another world…”

Younger volunteers who had no previous nursing experience. “When the end came, Finally, when the end – It took everyone’s breath away.”

Munition Workers

British working class young girls in their late teens and early 20s. Paid less than their male counterparts, but making more money than in any previous pre-war work.

Women who were quite simply cogs in the war machine whose health and welfare were never given a second thought. “Well I’d got this bad throat, you see, and the doctor, he said it was some kind of poisoning.”

Women who lost sisters who worked beside them in the factories, “…she died before she was 20…They reckoned the black powder it burnt the back of her throat away.”

Women Bearing Witness

Black American women who bore witness to the racist policies and ongoing discrimination that Black American soldiers and nurses faced throughout the war. “To represent the womanhood of our race in America – these fine mothers, wives, sisters and friends who gave the flower of their young manhood to the ravages of war.”

European women, many of them socialists and internationalists, who exhorted their sisters in the combatant nations to speak out against the war. “Women of Europe, when will your call ring out?”

The creative team who developed Letters feels strongly that visualising World War One through diverse women’s original writings helps to address the previously absent narratives of women’s war experiences. We are deeply grateful to the scholarship done in recent decades that has brought women’s writings into the war’s history where it rightfully belongs and where women’s voices can be expressed and heard – and honoured – through the arts.

To find out more about Letters That You Will Not Get: Women’s Voices from the Great War, you can listen to our interview with Susan Werbe and Kirtsen Volness on the Visualising War podcast. You can hear some more excerpts of Letters here.