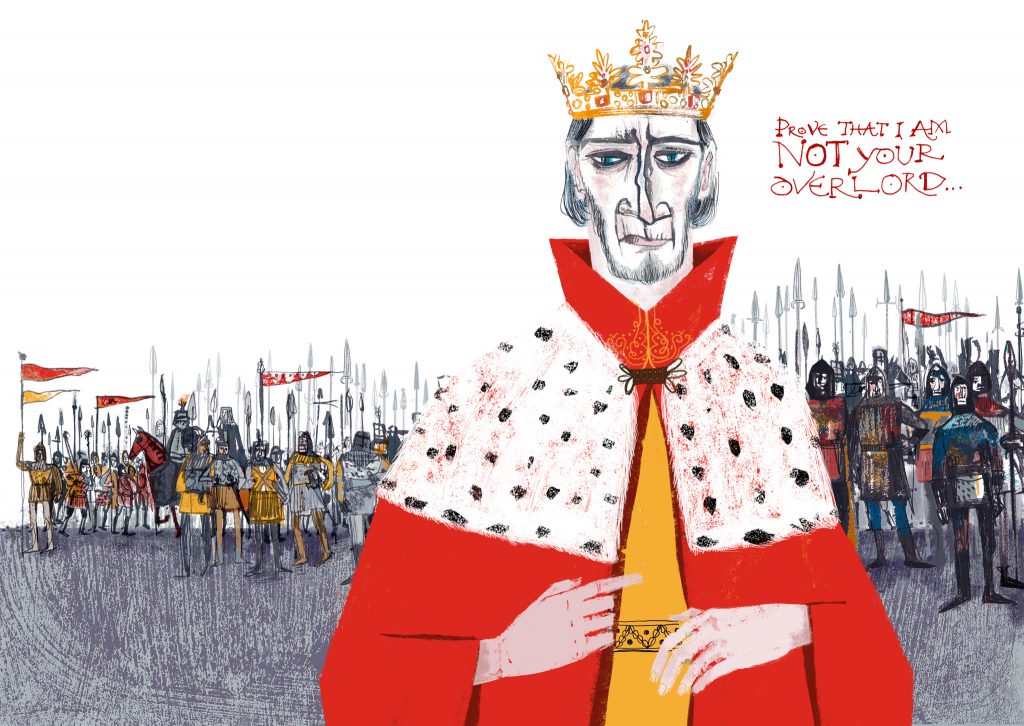

One summer, illustrator and book designer Jim Hutcheson was exploring the wares in a small bookshop in Spain when he came across an illustrated history of the life of Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, a Castilian knight also known as ‘El Cid’ or ‘El Campeador’. That got him thinking about the representation of other medieval warriors in literature, especially children’s books, and inspired him to commission artist Jill Calder and author James Robertson to create a new illustrated history of Robert the Bruce (published in 2014 by Birlinn).

Robert the Bruce is famous for many reasons, but particularly for leading the First War of Scottish Independence, so Jill, James and Jim quickly began wrestling with how to represent war and violence in art and text. The Visualising War podcast caught up with them recently and we had a fascinating discussion about the decisions they made and the impact which they hope their work will have.

The pivotal event in any account of Robert the Bruce’s life has to be the Battle of Bannockburn (1314), which resulted in an unexpected victory for the Scots over Edward II’s English forces. Jim, Jill and James dedicated 8 of the 64 pages in their book to narrating this, but they also wanted to take time over the events leading up to it, to help readers understand how that battle came about and how much violence had already preceded it on both sides. James talked particularly about the ‘Douglas Larder’ incident. Sir James Douglas was a Scottish landowner whose castle was occupied by English soldiers. On Palm Sunday in 1307 or 1308 (so the story goes), Douglas and his followers used a church service as cover to launch an attack on soldiers from the occupying garrison, killing many. He took surviving prisoners back to the castle and sat down with his men to enjoy the meal which had been prepared for the garrison on their return from church. Once full, he raided the castle stores and then gathered the remaining supplies in the cellars, where he proceeded to behead all the captives, piling their bodies on the stores and setting fire to them – as a grim warning to future occupying forces of what violence might befall them.

As well as giving readers a sense of just how violent the period leading up to Bannockburn was (English forces were acting with equal brutality towards any Scots they captured), James was keen to narrate this incident in a way that prompted comparisons with modern conflicts and atrocities, raising the question ‘Was this a war crime?’. Jill’s illustrations helped with this. As she explains on the podcast, she felt she could not shy away from the violence, even though the book they were creating was intended for younger readers. She did lots of research for her artwork, studying medieval sources to get details of clothing and weaponry right, for example, but also examining modern representations of conflict to inform her own. For the Douglas Larder story, she ended up basing her illustration on images of violence and retribution from local ‘wars’ between rival Mexican drug cartels. As she put it, this kind of theatrical violence – designed as a warning, as much as a punishment – is still going on in the world today; so, as well as giving her representation of 14th-century events a gritty realism, the echoes of modern atrocities in her artwork nudge readers to ask questions about the world we are currently living in and not just about Medieval ethics.

The picture Jills paints is colourful, beautiful even, with vibrant red flames flickering and a few stars visible through a castle window. The decapitated heads do not stand out – they are slightly hidden by the flames. But the beauty of those flames draws readers in, inviting them to look more closely; and once a reader notices the heads, they cannot unsee them. James, Jill and Jim all remember being shocked but fascinated by certain descriptions or images of violence in the books they read as children, and their hope with this page was built on that experience. Through a mix of compelling storytelling and gritty realism, they wanted to give their readers an image that would stick, that would fascinate, absorb and horrify, prompting them to peel away the layers and think: What? How? Why?

When narrating Bannockburn itself, James and Jill had four double-page spreads to work with, which allowed them to combine panoramic representations with close-ups of individuals. James wanted to stress that Robert the Bruce would probably not have opted to fight the battle, given the choice, and took time to set out the careful preparations they made to try to even out the huge imbalance between the much larger English forces and relatively few Scottish troops. He also wanted to focus attention on what Bruce said to his men before the battle, to remind readers why the conflict had been going on all that time and what was at stake for the soldiers themselves, about to risk their lives in what was likely to be a fight to the death.

One of Jill’s illustrations helps set the scene with a map of the battlefield, showing the troops gathered on both sides just before fighting began. Another zooms in on a decisive moment, when two warriors – Robert the Bruce and Henry de Bohun – charged towards each other and Bruce put an axe through de Bohun’s head. As with the Douglas Larder episode, there is no getting away from the violence of this scene. In the centre, a spray of blood shoots up as Bruce’s axe drives down through de Bohun’s helmet. Jill thought long and hard about how to capture the effort and determination which that extreme act of violence must have required, showing Bruce with teeth gritted and eyes focused as the horses carry their riders past each other. The horses themselves provide an extraordinary commentary on what one man is doing to another in this moment: their wide eyes help capture the adrenalin, terror and horror of the battlefield encounter. As with her other illustrations, Jill’s depiction of violence here is stylised as well as realistic, with vibrant colours and exquisite details drawing readers in, so that they look with a mixture of fascination and shock as they grasp what is unfolding. As simple as it is, this illustration captures some universal truths about battle and war, helping readers visualise not just the moment in question but the brutality of conflict at all times and in all places.

During our chat, Jim, James and Jill reflected on the role that both fiction and history have to play in shaping our understanding of past and present conflict. The story of Robert the Bruce is a mix of myth and history, which makes it amenable to creative storytelling. Readers will discover things they did not know about Bruce and the Scottish Wars of Independence from James, Jill and Jim’s book; but they are also taken on a bigger learning journey because of the way in which the historical narrative can be retold with new emphases and used to prompt reflection on wider issues. In this illustrated history, we also see the way in which images of battle help add new layers to what a text can tell us, as well as vice versa. This book – aimed at children, but equally intriguing for adult readers – richly illustrates what sensitive representations of war can do: like some of the other children’s literature discussed in Part 1 of this blog, it makes people stop, think, recoil, worry and evaluate the rights and wrongs of what they have just read.

To find out more about representations of war in children’s books and James, Jill and Jim’s illustrated history of Robert the Bruce, you can listen to our interview on the Visualising War podcast.

Alice König, 27.6.21