I have just been looking at transcripts and videos of two of Barack Obama’s ‘funeral orations’ – one delivered at a vigil for those affected by the shooting of twenty primary-school children and six of their teachers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newton, Connecticut in December 2012, the other a very recent eulogy delivered at a service for Senator Reverend Clementa Pinckney who, along with eight others, was murdered in a white-supremacist terrorist attack at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church (EAMEC) in Charleston, South Carolina, earlier this month.

In both of these speeches, Obama speaks to the pain and grief of the victims’ families and friends. He offers testimony to the courage, character and achievements of those who were attacked. He lists their names of the dead in a manner which underlines both the loss of real individuals and the scale of the slaughter. One can’t speak for those directly affected, but from my vantage point, Obama always seems to say what is appropriate and necessary, and to speak from the heart. There is likely to be a special memorial service for those who have just been killed in Sousse – if you were asked to give a speech at such an occasion, what would you say? It is very hard to get it right.

Both the Sandy Hook and Charleston speeches also make searing political points: the need for gun control; the need for action on the ongoing scourges of racism and white-supremacist terrorism; the need to eradicate race-related social injustice in American society. The Charleston speech achieves all this through invocations of history and a re-orientation of rhetorical language. Obama interweaved themes of Christian ‘grace’ and forgiveness with an invocation of the proud history of the EAMEC and that of many other ‘black churches’ in the struggles to end slavery and oppression and to promote civil rights and social justice for African Americans. He placed the EAMEC massacre in the context of a long, shameful history of racist atrocities against black people across the centuries. Finally, while Obama did not explicitly label the alleged gunman as a terrorist, his phrasing clearly authorized that label as legitimate. This was significant given commentators’ concern that the media and politicians consistently avoid the term ‘terrorism’ to describe cases like the Charleston massacre.

So, ‘funeral orations’ can use the rawness and injustice of innocent deaths to demand social, political or military change. It would be interesting to see a full translated transcript of Hamid Karzai’s speech at a memorial service in March 2011 for those recently killed by NATO air attacks in Kunar Province, Afghanistan. Among the dead were nine children whom NATO conceded it had killed in error. Angry and upset, and in the presence of the relatives of the dead and injured, Karzai appeared to demand that NATO stop its military activities on Afghan soil altogether. His aides had to subsequently ‘clarify’ that Karzai was simply asking that NATO work much harder to avoid civilian deaths.

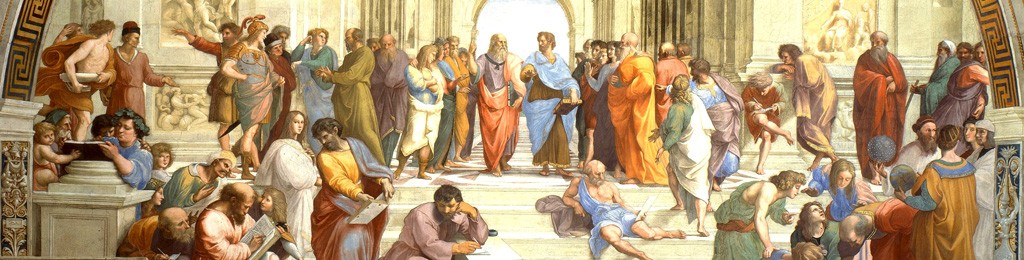

The orators of the classical Athenian democracy wrote and delivered powerful funeral orations too. At a special, annual ceremony held during periods of war – and Athens was at war an awful lot – the Athenians brought home the cremated bones of those who had died in battle for interment at a public burial site in the Ceramaecus. Thucydides describes how these remains were laid out in ten tribal coffins plus an extra one for those whose bodies had not been recovered. The burial ceremony was followed by a funeral speech delivered by ‘a man chosen by the polis’ (Thuc. 2.34.6). Plato’s Menexenus and Demosthenes’ defence speech On the Crown offer evidence that the choice of speaker was sometimes hotly debated in the democracy’s Council. Demosthenes makes much of the fact that it was he, and not his rival Aeschines, who was chosen to eulogize the conscripts who died at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. The most famous of these speeches is the one delivered by Pericles in honour of those who died fighting for Athens in 431/30 BC, the first year of the Peloponnesian War. We only have Thucydides’ ‘version’ of this speech and, when compared to other examples by Lysias, Demosthenes and Hyperides, it is suspiciously unusual – for example it doesn’t draw upon Athenian mythology in the way that all the others do. Then again, there are questions of authenticity attaching to all of the speeches and the one with the best claim to be what was actually said (Hyperides’) is also very distinctive in its extended and fulsome praise of the general Leosthenes, who died leading the Athenian insurgency against Macedon at the siege of Lamia in 323 BC. (On this speech and aspects of the funeral orations which make each one distinctively different from the others, see this article of mine).

However, this ‘naming and praising’ of one of the dead is exceptional for the surviving sample of this genre: these orations do not otherwise name the ordinary soldiers and commanders who have died in the previous year. There are no biographies, ‘citations’ or vignettes of their individual heroic actions either. Indeed, details and specifics of the relevant campaign are usually dealt with briefly. (Demosthenes’ funeral speech is rather different: nearly half the speech is focused on Chaeronea and the character and exploits of its Athenian casualties, although still in very general terms). The dead are simply referred to as ‘these man lying here’ and they receive praise for their goodness and courage regardless of whether their deaths were part of a victorious campaign or an unsuccessful battle. The emphasis of these speeches is rather on Athens’ past mythological and historical exploits in war: the Athenians of Theseus’ time defeated the Amazons and fought to recover the Argive dead from Thebes; the men of Marathon, Thermopylae and Salamis ensured Greece’s freedom from Persian rule; the Athenians and foreign allies who fought to restore democracy in the civil war of 404/3 (and so on). Out of 81 sections of (roughly) equal length, Lysias’ funeral speech for those who died in the war to assist the Corinthians (c.390 BC) devotes 62 of them to past Athenian campaigns.

The idea here, as Lysias puts it in his speech, is to ‘bring up the living to know the achievements of the dead’ (2.4) – in other words these funeral speeches are a means of re-telling, and adding to, a sort of ‘official history’ and ‘collective memory’ which will maintain each new generation of Athenians’ sense of their city’s importance and identity. But they also have a function of acculturating citizens to the notion that fighting and dying for the city is the ultimate accolade . As Lysias says of the conscripts who are his eulogy’s primary object: ‘they had been schooled in the bravery of their ancestors, and as adults they preserved the glory of their ancestors and displayed their own merits’ (2.70). The Athenian orations often stress that these fallen warriors have achieved a form of ‘immortality’.

This propagandistic aspect of the Athenian funeral orations is rather disturbing: it reminds us of Wilfred Owen’s ‘old lie’ or fundamentalist brainwashing . But from the perspective of a need to maintain and renew discipline and fighting spirit in a conscripted citizen-army of a fifth- or fourth-century Greek city state, sometimes in the face of what we would call ‘existential threats’, it makes good sense. The speeches of the Thucydidean Pericles and (to a lesser extent) those of Demosthenes and Hyperides also hold up Athens’ democratic constitution and way of life as things worth dying for.

Of course, this all seems rather different to the modern speeches with which I started: the former dealt with the deaths of unarmed, defenceless civilians rather than ‘combatants’. A closer fit might be the annual orations and ceremonies which remember the dead and wounded soldiers of past and more recent conflicts which take place in many countries across the globe. But there is an aspect to the recent acts of terrorism against worshippers at EAMEC and tourists in Sousse which sets up an interesting resonance with Demosthenes’ funeral speech (60.25-6). One of Demosthenes’ points in his speech is that the very nature of democracy promotes courage in the face of danger to life and limb. He argues that oligarchies and autocracies may create fear in their citizens but they do not instil a sense of shame. Thus citizens can bribe or curry favour with the regime to avoid military service and incur scant reproach because of the secrecy and information-control which such regimes enforce. But in a democracy like Athens, the existence of freedom of speech means that shameful conduct will be publically exposed:

‘Through fear of such condemnation, all these men, as was to be expected, for shame at the thought of subsequent reproaches, manfully faced the threat arising from our foes and chose a noble death in preference to life and disgrace.’

Now, we can’t tolerate, and shouldn’t have to show courage in, a situation where a visit to a church or a beach feels like risking death in battle. And, despite the statistical improbability of being caught up in an attack in most parts of the world, we shouldn’t dream of reproaching people for acting on their fear in the wake of the massacres in Charleston and Sousse. But Demosthenes’ rhetoric here is highly suggestive for what each citizen of a democracy needs to think about when their society comes under attacks designed to instil terror and division. If we completely yield to our fears of attack and banish all self-reproach and shame about the changes in attitude or behaviour which such a yielding entails, we will have lost those reservoirs of courage and risk-taking which are actually required to keep our societies free, rights-respecting and open enough to warrant the label ‘democracy’.

Tunisian citizens ran towards a heavily-armed terrorist in order to protect their European guests. The people of Charleston have come together and have not been deterred. These are powerful emblems of courage and resistance which today’s democratic orators would do well to commemorate.