Adrian Dunbar (Supt Ted Hastings) and Craig Parkinson (DI Matthew Cottan). Photo: BBC.

SPOILER AND CONTENT ALERT: if you haven’t yet seen all of BBC 2’s Line of Duty (Series 3), or read/seen Euripides’ Hippolytus this post contains some spoilers! As such, it also contains passing references to sexual abuse/violence.

Last week’s feature-length finale of Jed Mercurio’s Line of Duty was the most gripping and immersive episode of television drama we’ve seen in my household since, well, the previous week’s episode. A number of TV police dramas are addressing the painfully topical subject of police criminality, corruption, collusion, smear tactics, cover-ups and incompetence in the UK at the moment: BBC 1’s Undercover and ITV 1’s Marcella and Scott and Bailey also acknowledge and explore these subjects within the inevitable limitations of a prime-time entertainment slot.

One of the many striking things about the final Line of Duty was the length and intensity of two central interview scenes: they took up 54 minutes of a 90-minute episode. The first scene had DS Steve Arnott (an anti-police corruption officer in unit AC-12) being presented with the accusation and supporting evidence that he murdered former DI Lindsay Denton. It was then put to Arnott that he was ‘the Caddy’ – a corrupt detective who could call on a network of other officers to do the bidding of organized criminals and the murky forces of the establishment anxious to cover up past collusion and crime, including a child abuse ring involving a politician and a senior copper. We all knew Steve was innocent of these charges. And yet, his colleague and nemesis DI Matthew ‘Dot’ Cottan had done a masterful job at planting evidence against him and covering his own tracks. We watched with mounting horror as a sweating and indignant Steve had each of his alibis and explanations rebutted by forensic and circumstantial evidence. The exchanges got more and more heated and rancorous. Arnott hadn’t exactly played things by the book in a previous operation against Denton, and Cottan was able to use this to influence the mindset of the rest of the AC-12 team. By the end of the interview, it looked like Steve was going to cop for everything in a terrible miscarriage of justice. But we still hoped that Supt. Hastings and DS Fleming would pick up on Steve’s few good points in reply. Was he likely to have shot Denton at close range in his own service vehicle? And why were the supposedly incriminating contents of an envelope not covered in blood and DNA when the inside of the envelope was?

As I was watching all of this, it struck me that the dramatic dynamics were not dissimilar to scenes of debate, quarreling and interrogation which take place in Greek tragedy. These scenes follow certain conventions: one character will make a speech of 50 lines or more and then another will attempt to rebut them in a speech of matching length; such a so-called agon of long speeches will then morph into quick-fire exchanges of single lines (stichomythia) or pairs of lines (distichs). There is no rigid pattern to all this and every surviving tragedy does things differently. But the tension, irony and sheer excitement which these scenes of verbal confrontation must have created for ancient Greek audiences are easily lost on us as we read – they can look dry and artificial on the page. It takes good acting and directing in an actual modern production (or else a very vivid mind’s eye and ear) to recreate their edge-of-seat combination of vehement emotion, forensic argument and tit-for-tat rhetorical sparring.

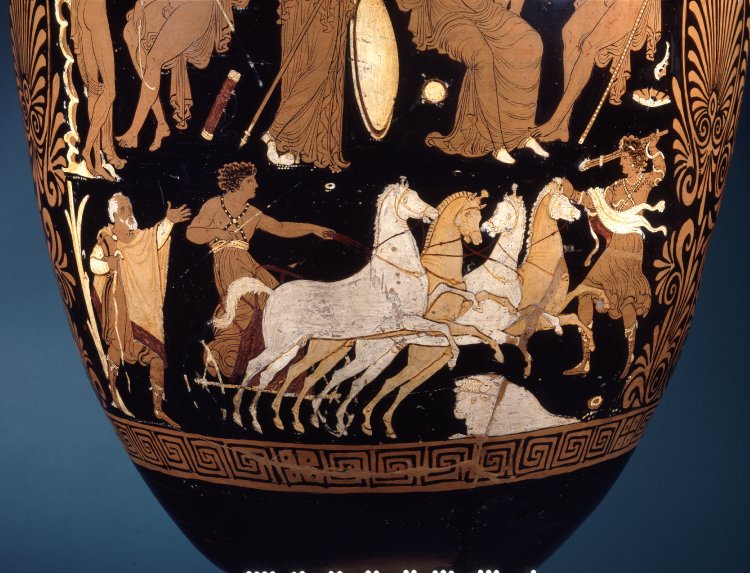

One such scene which has ‘the Line of Duty factor’ in spades comes in Euripides’ Hippolytus. After a long absence, Theseus returns to his palace in Troezen to discover that his wife Phaedra has just hung herself. As he grieves over her body he reads a suicide note in which she has falsely accused her step-son (and Theseus’ biological son) Hippolytus of raping her.

The truth – of which Theseus is totally unaware – is that the goddess Aphrodite had made Phaedra sick with desire for her step-son. The queen had reluctantly confided in her nurse about the cause of her sickness. The nurse then took it upon herself to act as a go-between. But when the nurse revealed Phaedra’s love for him to Hippolytus he was appalled, rejecting the overture and railing against all womankind. It is far from clear whether he will keep his oath to stay quiet or tell Theseus on his return. This prompts Phaedra to write the note and kill herself so that she can preserve her own and her children’s reputation.

Red-figured Apulian vase for mixing wine and water, c.340-320BC. Beneath an assembly of the gods, an old retainer looks on as a Fury and a bull terrify Hippolytus’ team of horses. Photo: British Museum.

So, when Hippolytus enters the action to be confronted by his step-mother’s dead body and his angry, grieving father, the audience knows that Hippolytus has been framed by the lying suicide note. The terrifyingly ironic disjunction between how things look to Theseus and the truth of what has gone on must have really smacked the audience in the guts. Even before Hippolytus has entered and pleaded his innocence, Theseus rushes to judge and punish him:

Theseus: O City! Hippolytus dared to touch my marriage bed by force, showing no honour to the revered eye of Zeus. Well, father Poseidon, you once promised me three curses; with one of these make an end of my son, and may he not escape this day if the curses you gave me are real.

Chorus: Lord, by the gods, take this back and undo this prayer: for you will recognize later that you are wrong. Listen to me!

Euripides has engineered a wonderful mixture of dread and suspense in his audience here. The untried nature of the curses leave open the possibility that this one against his own son might not work. (Although spectators also have reason think it will work: for a big spoiler see my asterisked note at the end of this post). And the chorus of women suggest that Theseus might yet be able to reverse it. But they themselves can’t explain why Theseus is making a terrible mistake: they have previously sworn an oath of silence to Phaedra. And at this point he isn’t listening to them properly anyway.

As Theseus denounces his baffled son in a long speech, it becomes clear that the heinous nature of the alleged crime and its consequences are not the only causes of Theseus’ extreme anger. As a particularly pious young worshipper of Artemis who espouses an ascetic and ‘pure’ lifestyle free of sexual contact, Hippolytus has apparently proved himself to have been profoundly dishonest and hypocritical: ‘flee from men such as these’, shouts Theseus, ‘for they chase you down with their pious words, while they devise shameful deeds.’ Now, as with Steve Arnott’s approach to anti-corruption policing, Hippolytus’ brand of piety is not without its flaws. But there’s some agonizing emotional realism at work here. Like Steve’s colleagues in AC-12, Theseus is upset by the thought that he has been utterly duped and betrayed by someone he was close to – someone he thought he knew well.

Hippolytus now gets to make his long defence in reply. Will he be able to convince the enraged Theseus of the truth? Ironically, his piety makes this a harder task: he doesn’t reveal Phaedra’s love for him or call the Nurse as a witness because he’s sworn an oath not to. Instead, he resorts to a form of forensic argument which serves Steve Arnott quite well – the Greek rhetoricians and lawcourt orators called it eikos: ‘argument from probability’ or ‘likelihood’. Hippolytus says that even if Theseus doubts his devotion to chastity, he must consider the improbability that he committed this crime. Why would he pursue Phaedra when there were more beautiful women he could have gone for? Did he somehow expect to take over Theseus’ house by marrying Phaedra as its heiress? That would be a mad thing to think. Was it because he wanted to usurp Theseus’ rule? Well, nobody sane or sensible wants that kind of power!

For all the similarities of tension and forensic back-and-forth, notice too that a difference between Line of Duty and Hippolytus is emerging here. Steve Arnott’s eikos arguments successfully cast a measure of doubt on Cottan’s version of events and Hastings and Fleming are given other reasons to question that account as the interview progresses. But Hippolytus’ appeal to probabilities just comes across as mildly insulting to Theseus and his dead wife. It makes things worse. And although he swears an oath by the gods that he never touched Phaedra, Theseus remains implacably convinced that the dead body and the note are all the evidence he needs. Blind to the fact that he is relying so heavily on the written word to convict his son, he says this: ‘it is the deed that proclaims you a bad man, it needs no words’. Hippolytus must go into exile immediately. In a heated, furious rapid-fire exchange between them, Hippolytus makes the important point that his father is circumventing due process and the gathering of further evidence:

Will you not first review the evidence of oaths, of pledges of good faith or of prophets’ utterances – but simply cast me from the land without trial?

When this has no effect, Hippolytus comes close to breaking his oath of secrecy. But he takes the view that such impiety would be pointless: ‘there is no hope that I could convince the man I have to convince’.

I’ll leave you to read, watch or recall the rest of Euripides’ tragedy for yourselves. And I’ll end by stressing this: despite certain instructive similarities in the dynamics of the interrogation scene in Line of Duty and Hippolytus‘ debate scene, some big generic and cultural differences remain. Line of Duty has its tragic elements – a fair share of moral ambiguity for example, and the sense that some of its characters are being groomed and controlled by higher powers. But Euripides offers a much bleaker, complex and absolute image of human fallibility and frailty than even the great Jed Mercurio can muster. I’m not saying Line of Duty isn’t very good. It is – I’ll be watching series 4. But Euripides will make you think and have you gripped too, surprise endings and all.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

(*) It’s important to know that at the point when Theseus enters to discover Phaedra’s body and the incriminating note, the audience already has information that Hippolytus will die. The goddess Aphrodite tells us right at the start of the play that Theseus will find out about the the incestuous desire she has inflicted upon his wife and that he will kills his son as a result of his own father’s divinely-gifted curses. Aphrodite’s plan is to infect Phaedra with desire for Hippolytus so that he can be punished for his irreverence: the young man spurns sex and marriage and refuses to worship the goddess. We hear too that Phaedra will die. But we don’t hear exactly how the two deaths will come about, which will come first, or whether they will be causally related. If you believe the information provided by Aphrodite short-circuits all the suspense and uncertainty, think about all those historically-based dramas, films and novels where we know the outcome and yet find ourselves in suspense over how that ending will be achieved. We can get so carried away by the action and our wish that disaster be averted that we even forget our foreknowledge.