When Dominic Cummings walked theatrically out of the front door of Number 10 eleven days ago, a new kind of political adviser had been given his marching orders. Cummings wasn’t simply a ‘spin doctor’ in the mould of Blair’s Alistair Campbell or Thatcher’s Bernard Ingham. Nor was he a West-Wing style ‘chief of staff’. It’s true that Cummings shares bits of DNA with various wonk-cum-guru precursors: Labour’s Andrew Adonis; the Conservatives’ Steve Hilton; various luminaries of the Behavioural Insights Team (aka the ‘Nudge Unit’) originally set up by David Cameron. But Dominic took the idea that policy advice and his own ideological aspirations should be grounded in ‘data’, ‘behavioural science’ and the possibilities of new technology to a whole new level.

Dominic Cummings leaves Downing Street on 13th November 2020. Image: Sky News.

Boris Johnson seems to have been very reliant on Dom’s advice, ideas and vision. But it’s hard to know the true nature and extent of his influence over the PM and the rest of government. It suits critics and opposition parties to exaggerate the power wielded by unelected advisers, especially when they ‘become the story’ in the way that Dominic did. The Barnard Castle debacle does suggest his indispensability at that stage of the Covid crisis. But Cummings’ controversial presence at the heart of government was undoubtedly useful as ‘political cover’ at times. He drew a lot of fire away from the PM and his ministers.

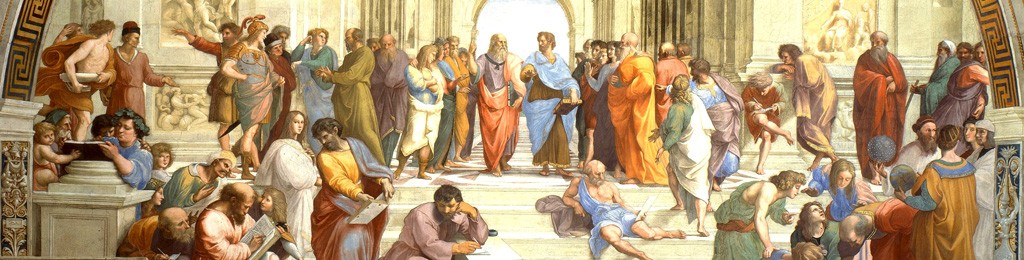

Classical Athenian politicians also had egg-headed advisers. And it looks as if the ancients were no less fascinated (and distracted) by their influence than we are with our own government’s special advisers and spin doctors. Historical sources often mention them in the context of a ‘game-changing’ decision or policy which they brought about. So, in the next few posts, I am going to bring you my 5 top-level nerdy political advisers to Athenian democratic politicians, complete with notes of caution about whether we should believe all that we read about them. They are arranged chronologically: it’s not really a ‘top 5’ ranking to be honest. And a list focused more generally on ancient ‘wise advisers’ would have different names on it. So please don’t @ me with ‘wot no Solon?’ etc.

1. Mnesiphilus (pronounced ‘Mness ee fill us’: if you’re on a Christmas Zoom party with your mates, it’s time to ease up on the Prosecco if you can’t say this name one syllable at a time).

A painting of the Battle of Salamis by artist Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1804–1874). Date: 1862. Oil on canvas, approx. 5 × 9m. Munich, Maximilianeum Collection.

Just before the battle of Salamis (480 BCE), this chap advised the great Athenian political leader and general Themistocles to assert his influence with the allies in order to prevent their planned retreat to the Isthmus. Or so says Herodotus (8.57). Having laid out the tactical reasons why Salamis is a good place to stay to engage the Persian fleet, Mnesiphilus spells out the situation with Cummingsian bluntness: ‘this is a stupid plan, which will spell the destruction of Greece.’ He tells Themistocles that he has to ‘find a way to reverse the decision – to persuade Eurybiades to change his mind and stay here’. Eurybiades was the Spartan commander of the fleet of the Greek confederation. Themistocles immediately takes Mnesiphilus’ advice without even replying to him. Thanks to a combination of his own rhetorical skill – he threatens to withdraw the Athenian fleet from the confederation if the withdrawal plan continues – and Eurybiades’ fear of having to face the enemy without the Athenians – the Greeks all stay at Salamis and win their famous victory.

Later writers represented Mnesiphilus as a teacher of practical wisdom in the tradition of Solon and as an adviser and friend of Themistocles (Plutarch Themistocles 2.6; Moralia 795c). 12 pot sherds with his name on them show that in 487/6 BCE Mnesiphilus was nominated to be ostracised [link] from the city. Whether this means he was politically active or was just regarded with suspicion because of his connections with Themistocles is impossible to say.

We’d be right to question the historical veracity of Mnesiphilus’ epoch-making intervention over Salamis. In Herodotus, this is his only appearance and mention. And it may be that this story comes from a ‘fake news’ source hostile to Themistocles: if Mnesiphilus was known to be one of Themistocles’ close advisers, this story was a good way of detracting from Themistocles’ alleged self-generated cleverness and cunning. Furthermore, Mnesiphilus’ language (‘stupid planning’: aboulia) taps into one of the big narrative themes of classical Greek history writing: the importance of good decision-making and practical planning (euboulia) in political and military affairs and the difficulty of achieving them.

On the other hand, you could argue that this story actually makes Themistocles look good. Unlike certain Homeric forebears (Agamemnon, Hector…) and the autocratic Persian king Xerxes in Herodotus’ own narrative, Themistocles actually listens to good expert counsel and saves Greece as a result.

But it’s perhaps less important to worry about whether this episode really happened or not than it is to reflect on what signals it might have sent to its first Athenian readers at the other end of the fifth century BCE. One of the positive aspects of Athens’ direct democracy when it worked well was that its citizens had good mechanisms for listening to, and acting upon, the advice of other citizens with authentic relevant experience, expertise and practical wisdom. But one of its negative aspects was the ease with which that sort of advice could be drowned out by rhetorically beguiling and stirring arguments in favour of a much more stupid and ill-informed course of action.

Our feelings about the likes of Dominic Cummings shouldn’t lead us to think that all unelected experts and advisers are a bad thing for democratic governance and good planning.

Nerd number 2 will be a clever bloke who advised Pericles called Damon! Bet you can’t wait…