There has been a lot of talk about Nigel Farage’s ‘attack on the audience’ in last Thursday night’s election debate on BBC television. In the context of a discussion about immigration, the UKIP leader said that the studio audience shared the other party leaders’ ‘total lack of comprehension.’ Farage continued that it was ‘a remarkable audience …even by the left-wing standards of the BBC’, adding ‘this lot’s pretty left-wing.’ The debate moderator, David Dimbleby (for it was He), pointed out that the audience had been carefully chosen to represent of a balance of opinion across all the parties by an independent polling organization. Farage archly echoed Dimbleby with ‘very carefully selected’ and added ‘the real audience are sitting at home, actually’. This provoked a collective noise from the studio audience: it sounded like a mixture of shock, derision and vocalized taking-of-offence. I think it was a higher-pitched version of the sort of crowd-based hubbub which the ancient Greeks called ‘thorubos’: a lovely onomatopoeic word which comes to life when you watch footage of massed crowds of male factory workers at strike meetings in the 1970s.

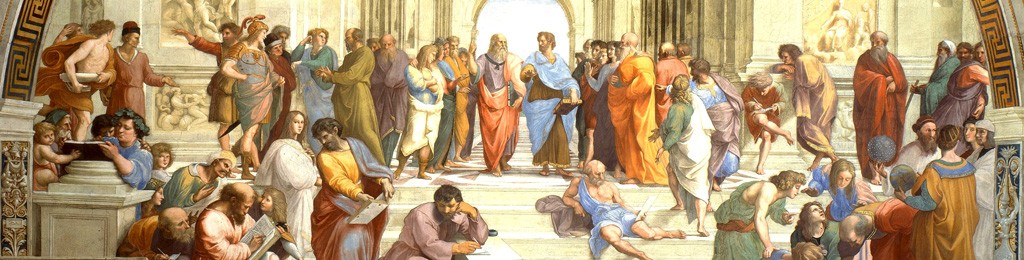

With democratic assemblies of thousands and with juries which could go into the hundreds, the presiding officials and orators of classical Athens were used to the inevitable interruptions of audience thorubos and sometimes seem to have encouraged it. But even Dimbleby’s experience doesn’t quite go back as far as the fourth century BC, so he quickly shushed everyone and asked that Nigel be allowed to have his say.

In the midst of all this, Ed Miliband chipped in: ‘it’s never a great idea to attack the audience, Nigel, in my opinion’. Nicola Sturgeon also joked in terms which implied that Farage’s outburst was an own goal. On Radio 4’s Broadcasting House , Norman Smith, the BBC’s assistant political editor, explained this notion further:

‘…what left so many seasoned politicians literally shaking their heads in disbelief was that in having a go at the Beeb…worse, having a go at the audience…Nigel Farage broke one of the cardinal rules of modern politics, namely: don’t moan about the messenger. At least not in public. It’s bad politics. Very, very bad politics. It looks like self-pity, an excuse, a whinge.’

There are some superb classical Greek oratorical examples of ‘audience attack’ in political debates which help us to question the assumption that it’s always bad strategy to attack one’s audience. I promise to get to these in my next post. For now, let’s stick with Nigel. As someone who is often thinking about rhetorical representations of ‘audience’ in ancient texts, I can’t help thinking that Norman Smith’s analysis underestimates Farage’s rhetorical and political savvy.

Nigel was very isolated in that debate hall on Thursday night – remember that it was him versus four ‘progressive’ left-of-centre parties with no Clegg or Cameron in between. Because of my own political views, I was perfectly happy to see the UKIP leader left out on a limb. But what he was thinking about was how this looked and sounded to millions of voters at home. UKIP claims to represent the views of many ‘ordinary’ people – Hillary Clinton now calls them ‘everyday people’ – who have been ignored by the ‘politically-correct metropolitan elites’ (etc.). The UKIP narrative is that its values and policies run counter to the dominant political and media culture and yet are actually very popular. Of course, that narrative only gets close to reality in a few parts of the country and UKIP’s performance in opinion polls suggests that it has got a lot of work to do in the popularity stakes.

However, the narrative is still a clever one, because it is rhetorically constitutive or constructive whilst appearing to be merely descriptive. ‘What the hell are you talking about, Jon ?’ , you are now shouting, I’m sure. Well, the UKIP narrative is all about creating more support by openly acknowledging that mainstream public discourse has placed a big question mark over the moral and democratic-political acceptability of voting for this sort of party. In response to that big question, the narrative licenses new support for UKIP through its appeals to relative authenticity (‘actually’, ‘really’) and the reassuring authority provided by the claim that UKIP policies are latently very popular. The narrative says: ‘it’s okay and right to have these views because they are actually shared by many. Come out of hiding and join the millions of real people who agree with us’.

But the persuasiveness of this narrative starts to unravel if potential voters watch a debate in which the UKIP leader is rarely clapped or cheered and where his four rivals – all of whom have managed to come across as less stuffy and ‘elite’ than Farage himself – find it easy to speak with unanimity against his pronouncements. What those voters were starting to see at home on Thursday night was a very unpopular populist politician. Where was the evidence of grassroots support from ‘real’ people?

This is why Nigel suddenly declared that the studio audience weren’t a real audience (or the real audience) at all. Accusations of BBC bias aside, he implicitly questioned whether this very tiny fraction of the electorate could ever, with any real confidence, be felt to represent the real balance of opinion in the country. His tactic suggested that plenty of television viewers at home were openly or secretly agreeing with him and, by virtue of their relative numbers, they were more important than ‘this lot’ in the studio. In a strong sense, then, Farage wasn’t ‘attacking the audience’ at all. He was saying that it was a pseudo-audience. He was simply, but very cleverly, attempting to persuade the debate’s main and most important audience that his in-studio unpopularity was a mirage created by an inauthentic media event.

It feels ironic that Nigel, of all people, ended up deploying an essentially postmodernist rhetorical gambit with very identifiable roots in late twentieth-century French thought.

A final thought. I don’t for one moment believe that Miliband and Sturgeon really thought that Farage’s attack on the studio audience was a bad strategy born from political gaucheness. They surely knew that he was attempting something much more sophisticated. But by calling it out as a laughably bad move and labelling it as ‘an attack on the audience’, they constructed an effective counter-narrative to Nigel’s. And Dimbleby actually helped them along. In that counter-narrative, the studio audience was a genuine ‘part-for-whole’ (or ‘synecdoche’ for all you fans of ancient rhetorical devices). It was a real and fair miniature sample of the wider electorate. That counter-narrative seems to have won the day and, in this case, it was probably the truer one. But the whole business should cause us to pause and think about the ways in which our views might be swayed by possible manipulations or exclusionary constructions of ‘audiences’ and ‘mini-publics’ in, and by, the media and its participating politicians.