When Ed Miliband gave his leader’s speech to the Labour Party conference in Manchester last year, it caused quite a stir. He spoke without the aid of notes or an autocue for 65 minutes. A former adviser to Tony Blair called the speech ‘a spectacular performance, remarkable for the cogency and fluidity of delivery. Its real strength was authenticity and the raw, at times poignant, emotion’. And the Conservative pundit Tim Montgomerie drew attention to the significance of the speech’s ‘off the cuff’ feel: ‘After today we know that Ed Miliband can deliver a speech without notes and with passion. David Cameron will testify to the fact that that counts. He largely won the Tory leadership on the back of a similarly delivered speech at the Tory conference of 2005′.

Ed Miliband delivers his keynote speech to delegates during the annual Labour Party conference in Manchester. Photograph: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

There is something about a fluent (and yet authentic and heartfelt) speech delivered without written aids which impresses and affects us. Of course, Miliband practised this speech with the aid of writing and he was open about doing so. This article in the Independent reveals that he divided the text into 11 sections and then memorized them systematically. The text was 5000 words long and meant to last 50 minutes but the live version ended up running to 6500 words. We are told that ‘every time he practised the speech it came out slightly differently’.

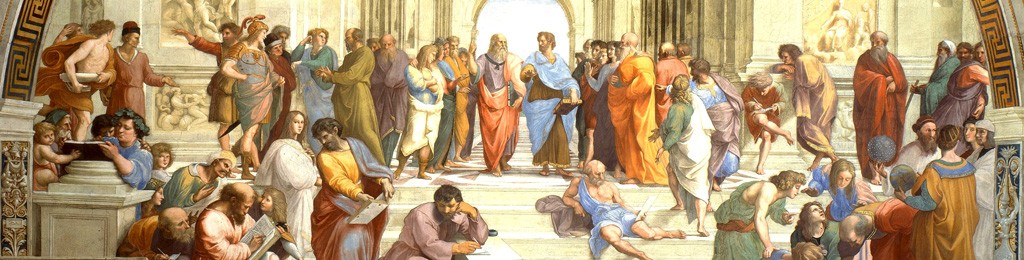

By throwing away their lecterns and auto-cues, modern politicians are in many ways returning to the traditions of ancient Greek and Roman oratory. In antiquity, there was an expectation that an orator would speak without notes in law-courts and assemblies. This is why, by the early first century BC, ‘memory’ (mnēmē in Greek, memoria in Latin) becomes one of the five basic divisions of tasks within the orator’s craft as outlined in rhetorical handbooks and homilies (Cicero On Invention 1.9, The Rhetoric to Herennius 1.3, Quintillian Institutes of Oratory 3.3.1).

The anonymous handbook Rhetoric to Herennius contains the earliest systematic treatment of how an orator should go about memorizing his speech, although he refers somewhat disparagingly to earlier Greek treatments of the topic now lost to us (3.16.28-24.20). The author of this treatise recommends that the orator develop an ‘artificial memory’ by creating a series of images of ‘backgrounds’ (loci) for himself: for example a house or an archway. These are memorized in a fixed order. Then, the orator places images representing phrases, events and arguments he needs to memorize against the backgrounds. In this way, the speaker ends up with a system of mental visualization and recall which allows him to memorize the order and content of his speech.

Interestingly, this system also seems to envisage law-court situations where the orator needs to respond, ‘on the spot’ and ‘off the cuff’, to the evidence and arguments put by the other side. If the prosecution alleges that there are many witnesses to the defendant’s act of poisoning, the defence speaker remembers that he must respond to this point by visualizing an image of the victim which includes ram’s testicles! (3.20.33). This is because the Latin word for testicles (testiculi) is close to the word for witnesses (testes).

We cannot be sure how far great politicians and advocates like Demosthenes and Cicero used these recommended mnemonic systems or found techniques of their own. One question which scholars still wrestle with is the nature of the relationship between the surviving texts of these ancient orators’ speeches – some of which are extremely long and detailed – and what they actually said on the occasion of their delivery. There is some evidence that Athenian law-court speeches were revised and expanded before publication and after the event in order to impress potential clients or to carry on politically-charged disputes beyond the realm of the public courts.

But the question remains as to whether Demosthenes wrote out and polished all of his more gargantuan law-court speeches (for example, On the Crown) and learned them off by heart or whether the texts we have represent a different process of re-composition in writing after a live performance of what was largely a feat of mental and oral rehearsal using some kind of mnemonic system. The fact that Demosthenes wrote speeches for clients and was often attacked by opponents for being a ‘sophist’ and ‘logographer’ (speech-writer for hire) might suggest that he used the former method. But either method makes Miliband and Cameron’s feats of oratorical memory look like small beer by comparison: the live version of On The Crown would have taken at least two hours to deliver – maybe considerably longer. And that was just one among many legal and political speeches which would have been delivered by him in any single year.