We have just a day and a few hours to go before the General Election. It’s hard to overstate the significance of this ballot for the future direction of our union of countries. The Conservative Party has a lead in the polls. Its leader, and our current PM, is Boris Johnson. In the light of Johnson’s classical training and his fondness for the ancient Greeks, he has done three things that interest me in this election campaign. The first of them I will label avoidance of scrutiny and being called to account.

Johnson is the only main party leader who has not done an in-depth long-format interview with the BBC’s veteran political journalist Andrew Neil. It seems that the BBC went ahead with this series of interviews because it understood that Johnson would indeed sit down with Neil for a televised grilling, just as the other leaders have now done. But the BBC never managed to get Johnson to agree a time and date for the interview. And with less than two days to go before the polls open, Johnson is saying that he will not do the interview before the General Election. In response, Andrew Neil did an extraordinary piece to camera. Neil highlighted the atypicality and political significance of Johnson’s refusal to sit down with him:

Johnson is the only main party leader who has not done an in-depth long-format interview with the BBC’s veteran political journalist Andrew Neil. It seems that the BBC went ahead with this series of interviews because it understood that Johnson would indeed sit down with Neil for a televised grilling, just as the other leaders have now done. But the BBC never managed to get Johnson to agree a time and date for the interview. And with less than two days to go before the polls open, Johnson is saying that he will not do the interview before the General Election. In response, Andrew Neil did an extraordinary piece to camera. Neil highlighted the atypicality and political significance of Johnson’s refusal to sit down with him:

‘Leaders’ interviews have been a key part of the BBC’s prime-time election coverage for decades. We do them, on your behalf, to scrutinise and hold to account those who would govern us. That is democracy.’

Neil goes on to point out that Johnson can’t be legally compelled to submit to this kind of scrutiny. And it is perhaps a weakness of modern British democracy that government ministers can, if they wish, avoid awkward questioning and truly forensic scrutiny to a remarkable degree. Between election campaigns, we do at least now have the select committee system. Since 2010 these committees have been given more teeth (in order to restore some balance to the relationship between the executive and the House of Commons). And of course, all ministers are required to answer for their actions and policies when Parliament is sitting.

But it is only really via the media scrutiny which accompanies elections that a politician’s overall character, career history and track-record can be called to account. These days, however, it is possible to hide from such scrutiny or else to distract the scrutineers with ‘dead cat’ strategies and ‘fake news’ about opponents. An individual politician’s track record of dishonesty and incompetence is easily masked by the wider canvas of party-political struggle. Admittedly, Johnson nearly found himself prosecuted on the charge of ‘misconduct in a public office’ earlier this year. (This was over his side-of-a-bus £350 million claim during the 2016 referendum). I might have missed something but, as far as I can see, no elected official has been successfully prosecuted for this very old and vague common law offence on the grounds that they knowingly made false statements or broke pledges to their voters.

In Classical Athenian democracy, it wasn’t so easy to hide from scrutiny and accounting. Every public official had to submit to an examination of his conduct in office at the end of his term. This was called a euthunē: literally, it means ‘the action of setting straight’.

If the official had been responsible for managing public money he had to present his accounts to a board of ten logistai (‘accountants’). But in all cases, he had to gain approval for the way in which he’d used his powers to a board of ten euthunoi (‘straighreners’) appointed by the Council. Any citizen could use this process to raise objections to the official’s conduct in office. It was up to the euthunoi whether the complaint was dismissed or passed on to the democracy’s courts. In the fifth century BCE, it was not uncommon for fines to be issued when accounts were found wanting or complaints were upheld. In the fourth century BCE, the euthunē process was joined by another procedure called the eisangelia. This literally means ‘a laying of public information’ and, in cases when it was a public indictment used against public officials, it is often compared to the process of ‘impeachment’ in the United States of America. An eisangelia could be brought against officials while they were still in office or even against prominent politicians who moved proposals in the Athenian assembly – remember that any citizen could author such proposals in Athens. You didn’t have to have been elected or appointed to do so.

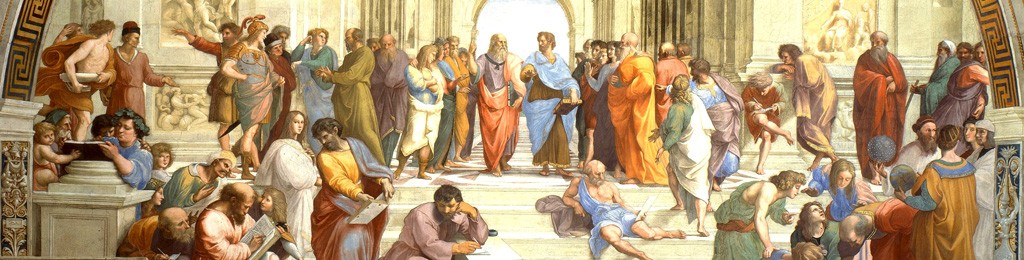

Stele with a relief showing Democracy crowning Demos (the people of Athens), ca. 337 B.C. Athens, Agora Museum, I 6524.

In Athens, even powerful elected leaders (stratēgoi) such as Themistocles and Pericles only had a single-year term of office at a time (although, like our bloody Prime Ministers, they could go on getting re-elected!). Alongside the less-used-than-you’d-think process of ‘ostracism’, this short term of office also created some level of accountability.

None of which is to say that Athenian democracy was free of lying and corruption on the part of its officials, elected leaders and self-appointed demagogues. But its evolving procedures of ensuring close scrutiny and accountability are testament to the Athenians’ sensible understanding that ‘the people’ (the dēmos) can only maintain their ‘grip’ (kratia) on power if their officials and leaders are subject to credible and regular tests of their honesty and competence. If politicians can now evade such tests from both our traditional and social media, then we might need to beef up our legal-constitutional mechanisms for ‘straightening’ the dodgy ones like Mr Johnson.

I do sometimes wonder whether Johnson is all too aware that we don’t have anything in place quite like the Athenians’ processes of euthunē and eisangelia. Catching him in a revealing moment on the campaign trail and making sure it goes viral isn’t going to cut it, after all.