- Introduction

- Becoming insane. George Trosse (1650s)

- Depression. Hannah Allen (1660s)

- Obsession. Alexander Cruden (1739)

- Religious lunacy. Dionys Fitzherbert (1610)

- Madness and genius. James Boswell (1778)

- Religion and recovery. William Cowper (1764)

- Compulsive and delusional behaviour. John Philip (1777)

- A poor clerk and a society heiress

- John Philip’s point of view

- Trial and committal

- John’s fate and that of his victim

- Protection or control? Alice Hill, ‘an idiot’ (1730s, 1740s)

- A ‘silent madness’. Hugh Blair (1747)

- Attempted suicide. William Cowper (1763)

- Suicide 1. Letters, diaries, and notes in the National Archives of Scotland

- Suicide 2. A London coroner’s inquest verdict, 1791

- Being an asylum patient 1: Cardiff Asylum regulations, 1919

- Being an asylum patient 2: Letters from the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, late 19th century

- Being an asylum patient 3a: Herman Charles Merivale admitted to Ticehurst, 1875

- Being an asylum patient 3b: Herman Charles Merivale at Ticehurst, 1875

- Being an asylum patient 4: Christian Watt at Aberdeen Royal Mental Asylum, 1877

- Fighting back. A ballad about William Frederick Windham, 1862

- Living with madness 1: an apprentice in danger, 1738

- Living with madness 2: an insane murderer, 1727

- Shell shock. ‘War Neuroses: Netley Hospital, 1917’

1. The voice of the mad. Introduction

FURTHER READING: A. Ingram, The madhouse of language: writing and reading madness in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1991).

Gail A. Hornstein, Bibliography of First-Person Narratives of Madness in English (5th edition). Available as a free download from her website, with other useful resources.

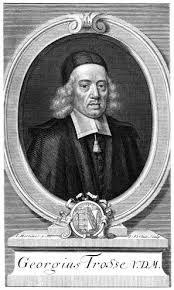

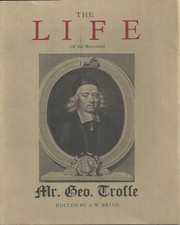

2. George Trosse (1650s) (2 extracts)

Extract 2.1 Becoming insane.

Trosse (YOONIQ Images)

SOURCE: The life of the Reverend Mr. Geo. Trosse, Late Minister of the Gospel in the City of Exon, who died January 11th, 1712/13. In the Eighty Second Year of his Age, Written by himself, and Publish’d according to his Order (Exeter, 1714), 46, 47, 50.

EXTRACT:

While I was thus walking up and down, hurried with these worldly disquieting thoughts, I perceiv’d a voice (I heard it plainly) saying unto me, ‘Who are thou?’ Which, knowing it could be the voice of no mortal, I concluded was the voice of God, and with tears, as I remembered, reply’d, ‘I am a very great sinner, Lord!’ …

[Trosse began to pray.] While I was praying upon my knees I heard a voice, as I fancy’d, just behind me, saying: ‘Yet more humble; Yet more humble.’ … I removed what I was kneeling on, but the voice continued: ‘Yet more humble; Yet more humble.’ … [Trosse stripped off his clothes.] And as I was thus uncloathing my self, I had a strong internal impression, that all was well done, and a full compliance with the design of the voice. In answer likewise to this call, I would bow my body as low as possibly I could, with a great deal of pain, & this I often repeated. But all I could do was not low enough, not humble enough. At last, observing that there was a hole in the planking of the room, I lay myself down flat upon the ground and thrust in my head there as far as I could. But because I could not fully do it, I put my hand in the hole and took out earth and dust, and sprinkled it on my head.

I was full of all manner of blasphemies and wicked passions, and was haunted with terrible distracting temptations to self-murther [suicide], and with a great many terrifying and disquieting visions and voices; which tho’ (I believe) they had no reality in themselves, yet they seem’d to be such to me, and had the same effect upon me, as if they had been really what they appeared to be.

The life of the Reverend Mr. Geo. Trosse, Late Minister of the Gospel In The City of Exon, who died January 11th, 1712/13. In the Eighty Second Year of his Age, Written by himself, and Publish’d according to his Order (Exeter, 1714), 46, 47, 50.

SPOKEN VERSION: Felix Langley

FURTHER READING: K. Hodgkin, Madness in seventeenth-century autobiography (Basingstoke, 2007).

Extract 2.2 Being put away. George Trosse (1650s)

SOURCE:The life of the Reverend Mr. Geo. Trosse, Late Minister of the Gospel In The City of Exon, who died January 11th, 1712/13. In the Eighty Second Year of his Age, Written by himself, and Publish’d according to his Order (Exeter, 1714), 53-5.

EXTRACT:

Being in this miserable distracted condition, and refusing to make use of any suitable and proper means, in order to my recovery, my friends had intelligence of a person dwelling in Glastonbury, who was esteem’d very skilful and successful in such cases. They sent for him. He came; and engaged to undertake the cure, upon condition that they would safely convey me to his house, where I might always be under his view and inspection; and duely follow his prescriptions. Hereupon, my friends determin’d to remove me to his house; but I was resolved not to move out of my bed; for I was persuaded that if I removed out of it, I should fall into Hell, and be plunged into the depth of misery. I likewise apprehended those about me, who would have pluck’d me out of my bed, to have been so many devils, who would have dislodg’d me. …

By their concurrent strength they at length prevail’d against me, took me out of my bed, cloath’d me, bore me out between them. They procur’d a very stout strong man to ride before me; and when he was on horseback, they by force bound me by a strong linen-cloth to him; and, because I struggled, and did all I could to throw myself off the horse, they tied my legs under the belly of it. All this while I was full of horrors and of Hell within: I neither opened mine eyes nor my mouth. …

Upon the way the men stay’d a little to refresh ourselves (for I was very troublesome to them by my continual struggling). … And when they put a glass into my hand to drink of it, methought I saw in the glass a black thing, about the bigness of a great black fly, or beetle; and this I supposed to be the Devil, but yet would drink it. At which desperate madness of mine, it seem’d to me that all were astonished. I fancy’d that every step I stepp’d afterwards, I was making a progress into the depths of Hell. …

When we came to the town, I thought I was in the midst of Hell: every house that we passed by was as it were a mansion in Hell, and it seem’d to me that all of them had their several degrees of torment. …

At last, by God’s good providence, we were brought safely to the physician’s house. Methought all about me were devils, and he was Beelzebub. I was taken off my horse, and expected immediately to be cast into intolerable flames and burnings, which seem’d to be before my eyes.

The life of the Reverend Mr. Geo. Trosse, Late Minister of the Gospel In The City of Exon, who died January 11th, 1712/13. In the Eighty Second Year of his Age, Written by himself, and Publish’d according to his Order (Exeter, 1714), 53-5.

SPOKEN VERSION: Felix Langley

FURTHER READING: K. Hodgkin, Madness in seventeenth-century autobiography

(Basingstoke, 2007)

3. Depression. Hannah Allen (1660s)

IMAGE: UNKNOWN LADY by Samuel Cooper (1609-1672), miniature painting, Green Closet at Ham House, Richmond-upon-Thames. Credit: Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: We do not know what Hannah looked like, but this image is of the correct period and it shows someone from the better-off middling sort – which was her social milieu. As a committed Calvinist she is likely to have dressed quite soberly.

SOURCE: Narrative of God’s gracious dealings with that choice Christian Mrs. Hannah Allen (London, 1683), 64-5, 69-70, 72.

EXTRACT:

Towards winter [1665] I grew to eat very little (much less than I did before) so that I was exceeding lean; and at last nothing but skin and bones; (a neighbouring gentlewoman, a very discreet person that had great desire to see me, came in at the back door of the house unawares and found me in the kitchen, who after she had seen me said to Mrs Wilson, ‘she cannot live, she hath death in her face’) I would say still that everything I did eat hastened my ruin; and that I had it with a dreadful curse; and what I eat increased the fire within me, which would at last burn me up. …

Thus sadly I passed the winter [1665-6] and towards spring I began to eat a little better. …

I spent that summer [1666]; in which time it pleased God by Mr Shorthose’s means to do me much good both in soul and body; he had some skill in physick himself, and also consulted physicians about me; he kept me to a course of physic … I began much to leave my dreadful expressions concerning my condition, and was present with them [the family] at duty [private prayer]; and at last they prevailed upon me to go with them to the public ordinance [church service], and to walk with them to visit friends, and was much alter’d for the better. …

As my melancholy came by degrees, so it wore off by degrees, and as my dark melancholy bodily distempers abated, so did my spiritual maladies also.

Narrative of God’s gracious dealings with that choice Christian Mrs. Hannah Allen (London, 1683), 64-5, 69-70, 72.

SPOKEN VERSION: Caroline McWilliams

FURTHER READING: Voices of madness: four pamphlets, 1683-1796. Edited by Allan Ingram (Stroud, 1997), vii-xxii, 1-21.

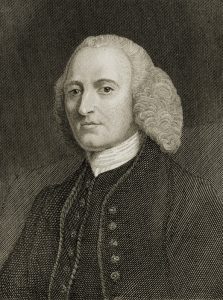

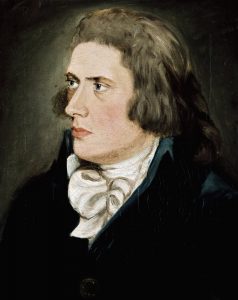

4. Obsession. Alexander Cruden (1739)

IMAGE: Alexander Cruden, 1700-1770. Credit: Design Pics Historical Collection / Universal Images Group. Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

SOURCE: The London-Citizen exceedingly injured (London, 1739), 1.

EXTRACT:

A short narrative is here given of the horrid sufferings of a London Citizen in Wright’s private madhouse at Bethnal-Green, during nine weeks and six days (till he made his wonderful escape) by the combination of Robert Wightman, merchant in Edinburgh, a stranger in London, and others who had no right, warrant or authority in law, equity, or consanguinity to concern themselves with him or his affairs; and yet more unjustly imprisoned him in that dismal place. How unjustly and unaccountably they acted in sending Mr C[ruden] to Bethnal-Green, and how cruel and barbarous they were in their bold and desperate design to fix him in Bethlehem (after Mr C refused to sign their pardon) that they might screen themselves from punishment, by covering one heinous crime with another more heinous, will appear by the following journal of Mr C’s sufferings.

The London-Citizen exceedingly injured: or a British inquisition display’d, in an account of the unparallel’d case of a citizen of London, bookseller to the late Queen, who was in a most unjust and arbitrary Manner sent on the 23d of March last, 1738, by one Robert Wightman, a mere Stranger, to a private madhouse Containing, I. An Account of the said Citizen’s barbarous Treatment in Wright’s Private Madhouse on Bethnal-Green for nine Weeks and six Days, and of his rational and patient Behaviour, whilst Chained, Handcuffed, Strait-Wastecoated and Imprisoned in the said Madhouse: Where he probably would have been continued, or died under his Confinement, if he had not most Providentially made his Escape: In which he was taken up by the Constable and Watchmen, being suspected to be a Felon, but was unchain’d and set at liberty by Sir John Barnard the then Lord Mayor. II. As also an Account of the illegal Steps, false Calumnies, wicked Contrivances, bold and desperate Designs of the said Wightman, in order to escape Justice for his Crimes, with some Account of his engaging Dr. Monro and others as his Accomplices. The Whole humbly addressed to the Legislature, as plainly shewing the absolute Necessity of regulating Private Madhouses in a more effectual manner than at present [anonymous] (London, 1739).

SPOKEN VERSION: Oli Savage

FURTHER READING: Voices of madness: four pamphlets, 1683-1796. Edited by Allan Ingram (Stroud, 1997), vii-xxii, 23-74.

5. Religious lunacy. Dionys Fitzherbert (1610)

IMAGE: PORTRAIT OF AN UNKNOWN LADY, of the English School 1660-1670 at Lyme Park, Stockport, Cheshire. Credit: Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: We do not know what Dionys Fitzherbert looked like, but this portrait may well represent the style of dress in the aristocratic circles in which she moved.

SOURCE: Women, Madness and Sin in Early Modern England: The Autobiographical Writings of Dionys Fitzherbert. Edited by Katharine Hodgkin (Farnham, 2010), 185, 187, 189.

EXTRACT:

Lying in this most lamentable case, how long I cannot tell, for I had not understanding to distinguish the day from the night; also they kept me somewhat dark, plying me with physic (which to give Dr Lister – then my physician – his deserved due was in all likelihood undoubtedly under God the only means of the safety of my life, in purging by his skilful potions those pestiferous humours). …

Then my brother brought the preacher to me … for I came to some better memory than I was. But then did Satan open the hideousness of my sin before me, as if it were possible to drive me to utter despair. … Howbeit they that were about me persuaded me that my sin was not so grievous as I made it, but that the nature of my disease caused me to speak I knew not what. …

But what I did or said while I was in that place afterwards I can by no means call to memory, nor how long I stayed before I was removed to Dr Carter’s, or why they did bind my hands. But most certain it struck an intolerable horror into my heart, thinking sure I had committed some crime they would put me to death for. …

But when they did remove me, which was in the night, they put a fair cloak and safeguard [overskirt] about me that Lady L[udlow] gave me; therefore I thought I had stolen it. … My brother, who was in the coach with me, told me I had not stolen it; but I thought he mocked me. …

They kept me a while at Dr C[arter]’s very dark, and I had some to watch me day and night. After a while they did remove me into a brighter room, where by reason of certain gestures [I] conjectured that they would burn me. …

Dr C[arter]’s wife, a very good gentlewoman and exceedingly carefully attending me many times with her own hands, with very great compassion often shown towards me, would stand and dress herself beside me. … Also the children would stand and stagger by me after their childish manner as if they were giddy, and one of them would say ‘God made this gentlewoman’s clothes’, which I thought their parents bid them do to show the vices I had been subject to, and that they said God made my clothes because I had stolen them, which I believed confidently I had done.

Women, Madness and Sin in Early Modern England: The Autobiographical Writings of Dionys Fitzherbert. Edited by Katharine Hodgkin (Farnham, 2010), 185, 187, 189.

SPOKEN VERSION: Rosie Beech

FURTHER READING: Hodgkin’s introduction to the source is superb or try another of her books, Madness in seventeenth-century autobiography (Basingstoke, 2007).

6. Madness and genius: James Boswell (1778)

JAMES BOSWELL (1740-1795).

IMAGE: JAMES BOSWELL (1740-1795). Caricature etching, 1786, by Thomas Rowlandson. Credit: The Granger Collection / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: This is a satirical image designed to caricature Boswell as a Scotsman, but it represents his facial appearance quite well.

SOURCE: The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, Volume 47 (1778), 58.

EXTRACT:

Why is it that all men who have excelled in philosophy, politics, poetry, or the arts, have been subject to melancholy?

Aristotle appears to have admitted the opinion that melancholy is the concomitant of distinguished genius, and indeed he illustrates the opinion with many remarks on real life, selecting at the same time renowned characters of antiquity, to whom melancholy was said to be constitutional.

We Hypochondriacks may be glad to accept of this compliment from so great a master of human nature, and to console ourselves in the hour of our gloomy distress, by thinking that our sufferings mark our superiority. I may use the expression ‘we Hypochondriacks’ in general and not be afraid of giving offence; though I should not choose to do it to any particular person, as there might be some danger from irritable delicacy. Hypochondriacks themselves are not agreed that they have reason to be vain, or proud of their malady; and even if that were the case, it might not be quite safe to single one out.

The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, Volume 47 (1778), 58.

SPOKEN VERSION: Oli Savage

FURTHER READING: A. Ingram, Boswell’s creative gloom (London, 1982).

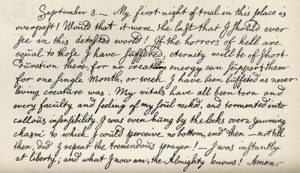

7. Religion and recovery. William Cowper (1764)

IMAGE: William Cowper by George Romney, 1792, drawing, pastel. Credit: National Portrait Gallery, London / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

SOURCE: Memoir of the early life of William Cowper, esq. (London, 1816), 97-8.

EXTRACT:

Immediately I received strength to believe it, and the full beams of the Sun of Righteousness shone upon me. I saw the sufficiency of the atonement be had made, my pardon sealed in his blood, and all the fullness and completeness of his justification. In a moment I believed, and received the gospel. Whatever my friend said to me, long before, revived in all its clearness, with demonstration of the Spirit and with power.

Unless the Almighty arm had been under me, I think I should have died with gratitude and joy. My eyes filled with, tears, and my voice choked with transport, I could only look up to heaven in silent fear, overwhelmed with love and wonder. But the work of the Holy Ghost is best described in his own words, it is ‘joy unspeakable, and full of glory’. Thus was my heavenly Father in Christ Jesus pleased to give me the full assurance of faith, and, out of a strong, stony, unbelieving heart, to ‘raise up a child unto Abraham’. How glad should I now have been to have spent every moment in prayer and thanksgiving! I lost no opportunity of repairing to throne of grace; but flew to it with an earnestness irresistible and never to be satisfied. Could I help it? Could I do otherwise than love and rejoice in my reconciled Father in Christ Jesus? The Lord had enlarged my heart, and I ran in the way of his commandments.

For many succeeding weeks, tears were ready to flow, if I did but speak of the gospel, or mention the name of Jesus. To rejoice day and night was all my employment. Too happy to sleep much, I thought it was but Iost time that was spent in slumber. Oh that the ardour of my first love had continued! But I have known many a lifeless and unhallowed hour since; long intervals of darkness, interrupted by short returns of peace and joy in believing.

My physician, ever watchful and apprehensive for my welfare, was now alarmed, lest the sudden transition from despair to joy, should terminate in a fatal frenzy. But ‘the Lord was my strength and my song, and was become my salvation’. I said, ‘I shall not die, but live, and declare the works of the Lord; he has chastened me sore, but not given me over unto death. O give thanks unto the Lord, for his mercy endureth for ever.

In a short time, Dr C[otton] became satisfied, and acquiesced in the soundness of my cure; and much sweet communion I had with him, concerning the things of our salvation. He visited me every morning while I stayed with him, which was near twelve months after my recovery, and the gospel was the delightful theme of our conversation.

Memoir of the early life of William Cowper, esq. (London, 1816), 97-8.

SPOKEN VERSION: Henry Roberts

FURTHER READING: J. Darcy, ‘Religious melancholy in the Romantic period: William Cowper as test case’ Romanticism 15, 2 (2009), 144-55.

8. Compulsive and delusional. John Philip (1777) ( 4 Podcasts)

8 (i) A poor clerk and a society heiress

PODCAST IMAGE: Head of Military Man by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, 1682-1754, oil on canvas. Credit: SuperStock/ Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: This image has been chosen to represent the darker side of John Philip’s character, rather than to portray his likeness

8. (ii) John Philip’s point of view

IMAGE: Portrait of Robert Fergusson (1750-1774). Painting by Alexander Runciman (1736-1785). Credit: De Agostini Picture Library / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Educational Use Only

NOTE: John Philip was about the same age as Fergusson, he may have moved in similar circles, and both he and Fergusson ended their days in Scotland’s only public madhouse, Edinburgh’s Bedlam.

8 (iii) Trial and committal

PODCAST IMAGE: Wellcome Library, London, L0080105. ‘Madeleine Smith at the bar of the Justiciary, Edinburgh’. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

NOTE: This is an image from the nineteenth century, but John Philip would have stood in the same place as the accused young woman, before a bench of judges and a jury of 15 men.

8 (iv) John’s fate and that of his victim

IMAGE: The House of Lethen, Auldearn: the family home of Miss Anne Brodie, daughter of Alexander Brodie and Henrietta Grant (Mrs Brodie). Canmore 15594, a/N/81.

NOTE: Anne built the west wing onto the original three-storey, 5-window wide house and made other alterations; further parts were added later.

SOURCE: National Archives of Scotland, JC26/212.

EXTRACT:

5 December 1776 declaration to William Thomson, one of the magistrates, by John Philip, prisoner in the city guard. He says that used to be his name but he is now Edward Brodie esquire of Lethen (which is how he signs the bottom right hand corner of each of the 13 sheets). John Philip acknowledges all letters above are by him. ‘Mr Colquhoun Grant sent for the declarant and the declarant having waited on him, Mr Grant desired to know why the declarant was writing letters to Miss Brodie, and the declarant being dissatisfied with Mr Grant’s behaviour on this occasion … challenged Mr Grant to fight him.

That in order to be properly armed, the declarant went to one Miller, a gunsmith, and asked him to give the declarant a case of pistols upon the pretence of being shown [to] a gentleman who was going to England.’ Also asked for a dirk or dagger, but was only able to obtain a sprint knife from a cutler called Orrock. ‘That the declarant’s purpose in being armed with a dirk was in case Mr Grant attempted to cane him or any person attempted to seize him, the declarant might stab Mr Grant or that person first and then himself.

That the declarant however returned same knife to Orrock betwixt the hours of two and four in the afternoon, thinking it improper or like a mad man to carry so dangerous an instrument about with him as the declarant upon second thoughts would not trust himself with it. That yesterday afternoon the declarant went a little bit into the country and tried his pistols by firing them three times when they answered well. That the declarant again loaded them and went to the Exchange Coffee house expecting Mr Grant to call upon him there.

That after waiting for some time and Mr Grant not appearing, the declarant wrote … copies of a declaration to be signed by Walter Orrock, the coffee house keeper, and his servant. That the declarant then went home and when there the declarant took the resolution of calling on Miss Brodie to get up his letters. That the declarant according went to the house of Mrs Brodie of Lethen and said to the servant who answered the door that he wanted to speak with Miss Brodie. That the servant asked his name, but the declarant was not permitted to see Miss Brodie, and that after a short scuffle with the servant the declarant was pushed out of the house and the door was shut.

That the declarant at this time had his loaded pistols in his pocket and putting his hand into his pocket where one of the pistols was he threatened with some abusive language to blow the servant’s brains out, but as he thinks did not take the pistol out of his pocket. That the declarant repeatedly rung the door bell and called to send the servant out that he might cane him, and this he did in a very rude and outrageous manner.

That the door was not opened, but the declarant had some conversation with Mrs Brodie and ladies from their windows, and the declarant behaved in a very rude manner to them, being much offended by the treatment he received from their servants. That the declarant finding he could not get access returned to town and changed his clothes in order to disguise himself and came back again to the house of Mrs Brodie with the loaded pistols in his pocket and rang the door-bell … with great violence and called for the servant to be sent out to him, but not getting access the declarant left the house and immediately met his brother William Philip, who took him aside and dissuaded him from again calling at Mrs Brodie’s house, telling him that Mr Colquhoun Grant was sent for and that the guard was there in order to take him prisoner.

That the declarant damned his brother and said he had nothing to do with him. That his brother followed him for some time, still insisting on him to go home and desired him to take care of his pistols as it was a dangerous affair and pressed so close upon the declarant that he the declarant suspected he might seize his pistols and therefore the declarant desired him to keep his distance, but he still begged of the declarant to go home. Which the declarant refused to do and soon after his brother left him and the declarant returned to the house of Mrs Brodie by himself, and after ringing again at the door bell with some violence, the declarant stepped back to the pavement and Mr Colquhoun Grant opened the door, calling out who was there? To which the declarant: ‘Mr Grant I want the servant out’.

That Mr Grant desired the declarant to come in, to which the declarant replied ‘I want the servant’. That Mr Grant immediately said ‘that is he: seize him’. And two guard soldiers directly rushed out of the house and attempted one to come upon the right hand and the other upon the left hand of the declarant. That the declarant damned the guard soldiers and said he would blow out the brains of the first man and offered to touch him, and that the declarant had then a loaded pistol in each hand.

That the soldiers seemed not to regard the declarant’s threats and as they advanced the declarant retired a little to about the middle of the street, but as the soldiers still kept advancing, the declarant snapped a pistol first the one and then at the other of them. That the declarant is not certain whether they both missed fire, or whether one of them flashed in the pan and the other snapped, but the declarant thinks they both missed fire.

That immediately upon this the declarant was knocked down and then seized and carried to the house, but before he was carried into the house he received several blows upon the face, and in particular the stroke that knocked him down wounded him severely in the head. That after the declarant was carried into the house he endeavoured forcibly to resist those people who held him and kicked and struck about with his hands as much as was in his power, and the declarant in consequence of this was thrown with violence on the floor and Mr Grant in particular held him very firm until he was bound hand and foot, and then the declarant was carried to the guard where he has remained ever since.

That soon after he was carried to the guard, the ropes were taken off and his hands were manacled and to the doing of this the declarant made no resistance. That the declarant’s brother, the above mentioned William Philip, has suspected for these six months past that the declarant was melancholy and unwell, and endeavoured by various and many teasing questions to know the cause of it. That the declarant sometimes told him he was going abroad and sometimes that he would follow his business as a writer.

That when the declarant talked of going abroad, he mentioned his having the expectation he had of a friend who would do something for him in Jamaica or London. That the declarant’s brother sometimes approved of his going abroad, saying he would find no master in his own way that would encourage him here, and at other times his brother would approve of the declarant’s following his business as a writer, and would sometimes say he would put the declarant in a way as to circumstances that would enable him to follow out his business.

That for some months past both his brother and the landlady with whom the declarant and his brother lodge have with their anxiety so much teased the declarant that he was perfectly tired of his existence and nothing but the declarant’s regard to Miss Brodie made him submit to stay in this country. That the declarant’s father has also behaved to him in the same disagreeable manner of late, in short that the declarant has found for these reasons that during the most of his apprenticeship with Mr Forbes that his life has been very uneasy and distressful to him.

That the declarant sometimes imagined that his brother suspected that he the declarant had a regard for Miss Brodie, or that Miss Brodie so far as the declarant could interpret from appearances had a regard for him. That in order to conceal this the declarant pretended a regard for some other young ladies until … the declarant saw Miss Brodie at the play when he suspected after he went to bed that she was going to be married that night and his mind was so much disturbed and agitated with this idea that he could not rest. That the cause of his suspicion was Miss Brodie’s coming to the play house in her carriage without a light and going away in her chair.

That the declarant got out of bed and after dressing himself he walked over to the New Town and past the house of Mrs Brodie and seeing all quiet he returned to the Exchange Coffee House to read the newspapers in order to discover if her marriage was there mentioned. That the declarant not finding it there mentioned he returned home and all this happened about eleven o ‘clock at night. That the declarant finding his brother asleep awaked him and told him of his the declarant’s attachment to Miss Brodie, alleging that his brother must know something of it, but of which his brother declared himself perfectly ignorant and even ridiculed the declarant for thinking of it.

That the declarant said his brother did wrong for if it was so he the declarant behoved first to kill the man that married Miss Brodie and then himself. And the declarant being asked to explain how he could reconcile his now calling himself Edward Brodie esquire of Lethen, and addressing Mrs Brodie as his mamma, with the former idea of making his addresses or marrying Miss Brodie, declares that this designation Edward Brodie esquire is only an idea he has entertained from this morning of being her brother.

National Archives of Scotland, JC26/212

SPOKEN VERSION: L. P. Catliff

FURTHER READING: Commentary for all four podcasts based on an original piece by Rab Houston, ‘A stalker in Georgian Edinburgh’, published in History Scotland magazine issue 1 (Winter 2001), 51-6. Find out more at www.celebrate-scotland.co.uk

9. Protection or control. Alice Hill, an ‘idiot ‘

V0030051 Young girl with Down’s syndrome.

IMAGE: Wellcome Library, London, V0030051. Young girl with Down’s syndrome, sitting, wearing striped socks. Photograph. By: Joseph Arthur Baldry after: George Edward Shuttleworth. Collection: Iconographic Collections. Library reference no.: ICV No 30534. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

NOTE: We do not know if Alice Hill had Down’s syndrome, but appearance was an important indicator of mental capacity in early modern times and she may well have looked distinctive.

SOURCE:

Extracts from the diary and autobiography of the Rev. James Clegg. Edited by Henry Kirke, M.A. (Buxton, 1899), 39-40.

EXTRACT:

29 May 1730. Mrs Creswell of Tideswell called on me to go with her to Disley to meet Mr Parr of Salford to procure Tuition of her daughter an Idiot a plot having been laid to steal her away.

14 July 1730. I went to Buxton to meet Mrs Adcroft and some Manchester friends [Quakers], and thence with them to Tideswell where I dined and settled some matters with Mr Eccles and Mrs Creswell relating to the Commission of Enquiry as to her daughter Alice’s Idiocy.

16 July 1730. The commission was opened at Townhead. Mr Chetham, Mr Parr and I were Commissioners (in Lunacy). The Jury were sworn, and witnesses examined and Alice Hill was found and presented an Idiot. This was done to prevent her being stolen away and ruined by a worthless fellow who had attempted it, and to secure her Estate for her use while she lives and to her right heirs after. Many censures pass on this proceeding, but knowing my intent in it to be just and right I have no reason to regard ‘em.

Extracts from the diary and autobiography of the Rev. James Clegg. Edited by Henry Kirke, M.A. (Buxton, 1899), 39-40.

SPOKEN VERSION: Hannah Raymond Cox

FURTHER READING: R. A. Houston, Madness and society in eighteenth-century Scotland (Oxford, 2000).

The diary of James Clegg of Chapel en le Frith, 1708-1755. Edited by V. S. Doe, 3 vols. (Derby, 1978-81).

10. A ‘silent madness’. Hugh Blair (1747)

IMAGE: James Robertson of Kincraigie; John Dhu (Dow, MacDonald); Jamie Duff by John Kay. Credit: National Portrait Gallery / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: Apart from having unusual personal habits, nobody described Hugh Blair as looking distinctive in any way. He may simply have seemed distant and detached. The image represents three well-known ‘characters’ with learning difficulties in Edinburgh around 1800.

SOURCE: National Archives of Scotland, CC8/6/15

EXTRACT:

16 July 1747 (at 3pm) interrogatories [questions] put to Hugh Blair by the Commissaries [judges] of Edinburgh with the said Hugh Blair’s answers [verbal].

When came you to town? Nickie Mitchell.

When came you to Edinburgh? Yes.

Where did you live before you came to Edinburgh? Edinburgh.

Do you hear me when I speak to you? Speak.

Did you ride or walk from the country? Ride.

Is this a fair day or rainy? Fair.

Is this a fair day or a foul? Foul.

Have you got your dinner? Hugh Blair.

Is your mother alive? Yes.

Came you from the west or from the east country? From the east.

Who made you? God. Being asked the same question a second time. Christ. And being asked the same question the third time. Holy Ghost.

What age are you? Hugh Blair.

Have you any brothers or sisters? Yes.

How many brothers or sisters have you? Yes.

What is the name of your parish minister? Brown.

How many fingers have you? At first he made no answer but his fingers afterwards being pointed to he counted the fingers of each hand twice without stopping.

Being desired to hold up his right hand he held up the left.

Is your finger or leg longest? Longest.

Is it forenoon or afternoon? Afternoon.

Is it forenoon or afternoon? Forenoon.

The said Hugh Blair being shown the Bible he read the first two verses of Genesis and being shown the title of the Old Testament and likewise of the New Testament both which titles he likewise read and being several times asked what book it was he hummed but made no articulate answer.

What brought you to town? Kirkcudbright.

What brought you to Edinburgh? Yes.

Being shown a guinea of gold and asked twice what it was he answered a shilling. And being shown a shilling and asked what it was he answered a shilling. And being shown a half penny and asked what it was he answered a half penny.

Being shown a pen knife and asked what it was he answered a knife. And being shown a pair of spectacles and asked what they were he answered glass.

Being shown a watch and asked what it was he answered: do not tell.

What is your name? Hugh Blair.

Whose son are you? Yes.

Can you write? Yes.

And having set before him in writing as follows: answer the following question. What brought you to Edinburgh? In place of giving an answer in writing when desired he transcribed verbatim the writing so set before him.

And he having thereafter set down in writing before him thus: you are not to copy what is set before you but write an answer to this question. What was the reason of your coming to Edinburgh at this time? And in place of giving a written answer he copied this over in the same way which writing is upon a paper hereto appended.

******

[in writing with Hugh Blair’s autograph response]

Answer the following question

What brought you to Edinburgh?

Answer the following question

What brought you to Edinburgh.

You are not to copy what is set before you but write an answer to this question: what was the reason of your coming to Edinburgh at this time?

You are not to copy what is set before you but write an answer to this question: what was the reason of your coming to Edinburgh at this time.

******

Are you married? Nickie Mitchell.

Is Nicholas Mitchell your wife? Yes.

Is Peggy Veitch your wife? No.

Do you live with Nickie Mitchell? No.

Do you live with May Gordon? Yes.

Do you live with Peggy Veitch? No.

Do you live with Mary Brown? Mistress Mitchell. Being asked a second time. Marion.

Was you ever in bed with Peggy Veitch? Nicholas Mitchell.

Whom do you love best? Nickie Mitchell.

One of the Commissaries having asked Hugh Blair if he would marry him he answered yes.

Is your wife alive? Wife.

Have you any bairns [children]? Bairns. And upon the question being put a second time. Yes.

National Archives of Scotland, CC8/6/15

SPOKEN VERSION: Matthew Lansdell (Intro: Oli Savage, Questions: Sebastian Bridges)

FURTHER READING: Rab Houston and Uta Frith, Autism in history. The case of Hugh Blair of Borgue (Oxford, 2000).

11. Attempting suicide. William Cowper (1763)

IMAGE: William Cowper by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1792, painting, oil on canvas. Credit: National Portrait Gallery, London / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

SOURCE: National Archives of Scotland, CC8/6/15

EXTRACT:

By this manner the time passed till the day began to break. I heard the clock strike seven and instantly it occurred to me, there was no time to be lost: the chambers would soon be opened, and any friend would call upon me to take me with him to Westminster. ‘Now is the time’, thought I, ‘this is the crisis; no more dallying with the love of life’. I rose and, as I thought, bolted the inner door of my chambers, but I was mistaken; my touch deceived me, and l left it as I found it. My preservation, indeed, as it will appear, did not depend upon that incident; but I mention it, to show, that the good providence of God watched over me, to keep open every way of deliverance, that nothing might be left to hazard. Not one hesitating thought now remained; but I fell greedily to the execution of my purpose. My garter was made of a broad scarlet binding, with a with a sliding buckle, being sewn together at the end: by the help of the buckle, I made a noose, and fixed it about my neck, straining it so tight, that I hardly left passage for my breath, or for the blood to circulate; the tongue of the buckle held it fast.

At each corner of the bed, was placed a wreath of carved work, fastened by an iron pin, which passed up through the midst of it. The other part of the garter, which made a loop, I slipped over one of these, and hung by it some seconds, drawing up my feet under me, that they might not touch the floor; but the iron bent, the carved work slipped off, and the garter with it I then fastened it to the frame of the tester, winding it round, and tying it in a strong knot. The frame broke short and let me down again. The third effort was more likely to succeed. I set the door open, which reached within foot of the ceiling; and by the help of a chair, I could command the top of it, and the loop being enough to admit a large angle of the door, was easily fixed, so as not to slip off again. I pushed away the chair with my feet, and hung at my whole length. While I hung there, I distinctly heard a voice say three times: ‘Tis over!’ Though I am sure of the fact was so at the time, yet it did not at all alarm me, or affect my resolution. I hung so long, that I lost all sense, all consciousness of existence.

When I came to myself again I thought myself in hell; the sound of my own dreadful groans was all that I heard and a feeling like that produced by flash of lightning, just beginning to seize upon me, passed over my whole body. In a few seconds, I found myself fallen with my face to the floor. In about half a minute, I recovered my feet, and reeling, and staggering, stumbled into bed again. By the blessed providence of God, the garter which had held me till the bitterness of temporal death was past, broke, just before eternal death had taken place upon me. The stagnation of the blood under one eye, in a broad crimson spot, and a red circle about my neck, showed plainly that I had been on the brink of eternity. The latter, indeed, might have been occasioned by the pressure of the garter; but the former was certainly the effect of strangulation; for it was not attended with the sensation of a bruise, as it must have been, had I, in my fall, received one in so tender a part. And I rather think the circle round my neck was owing to the same cause; for the part was not excoriated, nor at all in pain.

Soon after I got into bed, I was surprised to hear a noise in the dining- room, where the laundress was lighting a fire; she had found the door unbolted, notwithstanding my design to fasten it, and must have passed the bed-chamber door while I was hanging on it, and yet never perceived me. She heard me fall, and presently came to ask if I was well; adding, she feared I had been in a fit.

Memoir of the early life of William Cowper, esq. (London, 1816), 66-70.

SPOKEN VERSION: Henry Roberts

FURTHER READING: Rab Houston and Uta Frith, Autism in history. The case of Hugh Blair of Borgue (Oxford, 2000).

12. Suicide 1. Letters, diaries, and notes in the National Archives of Scotland (nine extracts)

IMAGE: James Hogg, The Suicide’s grave being the private memoirs and confessions of a justified sinner written himself (1895. First published as Private memoirs and confessions of a justified sinner in 1824). This is Hogg’s handwritten manuscript starting ‘September 8 My first night of trial …’. It appears just before the end of the memoir. Credit: Lebrecht Authors / Universal Images Group / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: Hogg’s narrative and the note are fictional, but they perfectly capture the desperation of the potentially suicidal.

SOURCE: [in order] National Archives of Scotland GD1/808/1/9; GD113/5/419/3/1; GD113/5/456/38; GD214/676/33; GD248/589/2/107/1-2.; GD406/1/11382.; CH2/12/1244; GD46/17/20, f. 44v; CC8/5/29/1

EXTRACTS:

![]() Listen to Extract 12.1

Listen to Extract 12.1

GD1/808/1/9

Andrew Murison of Troup, Banffshire, to his brother (14 April 1764)

‘Our news [from Edinburgh] are dismall with bankruptcys: a very melancholy scene happend here on Sunday last Robert Pringle, Lord Edgefield, one of the Lords of Session [a senior judge], & who some time ago was sheriff of Banffshire, went down to Leith after tea about 7 in the evening & threw himself over the peir in to the sea, where he drownd, he was taken up in about 20 minutes & blooded, but did not recover. The only reason that’s given is that, he was much in debt & could not extrecate himself.’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.2

Listen to Extract 12.2

GD113/5/419/3/1

Diary of Jane Innes

24 May 1793. Gossip among the polite Edinburgh set. Miss Trotter had called at Mr Fisher’s house and found it ‘in great confusion’. The housekeeper said Mr Fisher was ‘very ill indeed’ and when asked what was wrong simply pointed to the quantity of blood on the stairs. Others called the event an ‘apoplexy’ or stated that a blood vessel had burst. When pressed, family members said the event happened ‘having for some days before indulged too freely in the bottle, that he had weak nerves & his hand shook very much’.

25 May 1793. Further gossip among the young women who ‘could never get any distinct account’, but pieced together the story of Mr Fisher from various accounts: Miss Trotter said ‘that it was not apoplexy, that she had heard that he was dressing to come to dine with the young folks at Mrs Trotters & wishing to be very neat had insisted to shave over an ugly pimple on the side of his throat that the lad refused to do it, & attempting it himself a sudden shake of his hand had sent the razor throw his windpipe’. Despite immediate medical attention at the Infirmary he was still in great danger.

28 May 1793. Harry Trotter acknowledged Mr Fisher had cut his throat.

29 May 1793. Lady Dick at dinner talked of Mr Fisher as being ‘very unmanageable & furious when in drink, to which he was addicted’. Mrs Fisher and the minister had lectured him on his drinking, which had been at a high when his daughter recently married: ‘he had immediately thereupon sat down to write a letter addressed to Mrs Fisher in which he said he had resolved upon an effectual method to prevent exposing either himself or friends in the way she dreaded.’

Mr Fisher died 30 May 1793.

![]() Listen to Extract 12.3

Listen to Extract 12.3

GD113/5/456/38

In a letter to Gilbert Innes of Stow who was staying in Covent Garden (London), his estate factor at Pirntaiton near Edinburgh wrote (16 May 1807): ‘I notice your anxiety about Mr H’s death – you desire particulars – I need only tell you that the poor man was insane the night before. He talked of having seen ghosts and was afraid to go home lest he should be waylaid and murdered …’ The next day, while being escorted back to his own house ‘Mr Hall stopped and desiring Harvey to walk on he went over the enclosure [fence], deliberately cut himself across the right arm and also his throat and bled to death in a few seconds. What more need I say on so shocking a subject. I mentioned in my letter of the 29th what had probably been his motives, but am since informed that the sum he lost in town was not nearly so much as I then stated … The lower and more ignorant set of people grumbled excessively at interment in a church yard and we were afraid of opposition, but none was offered.’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.4

Listen to Extract 12.4

GD214/676/33

Suicide note of Major George Philips, 21 April 1806. ‘In two days past my mind has been strangely affected. I am incapable of the least application … The anxiety of mind consequent on the inability no doubt disturbs me but I suspect that fever or mercury have fallen upon my brain. … What the great depression of spirits I labour under may produce, God only knows. My conscience is free from deep guilt. I have done justice to every man … My will is perfectly valid as it was written in perfect composure of mind … I presume to hope that the father of all will freely forgive my trespasses … my head is disturbed.’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.5

Listen to Extract 12.5

GD248/589/2/107/1-2

John Ross to the Earl of Seafield, 27 November 1785. Letter concerns arrears by tenants.

‘I am now, my lord, under the necessity of mentioning a subject to your lordship, which cannot give you more vexation & uneasiness than it has done to collector Ogilvie & me. Alexander Wilson has again fallen short to your lordship for a sum above £500. Driven to despair by a consciousness of his own misconduct & ingratitude to your lordship, he made an attempt about a fortnight ago to put an end to his own life, and tho the attempt did not immediately prove fatal, I hear, from Dr Abernethy & Dr Duncan, that he cannot recover, & that he will probably die in a day or two. Every thing possible has been done, or will be done for your lordship’s indemnification. His effects, so far as we can learn, are very inconsiderable …’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.6

Listen to Extract 12.6

GD406/1/11382

Duke of Hamilton to his sister, late seventeenth century.

‘On Thursday last cousin Hambden to end all his misfortunes did cut his throat with a razor he is not yet dead but there is little hopes he will live and I hear he is penitent which makes me extremely to wish he may recover. It is a great instance of the vanity of all human attainments to see a man so greatly exerted [distinguished] almost in all things make so mean a conclusion of life.’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.7

Listen to Extract 12.7

CH2/12/1244

Suicide of Mr John McKain, (Presbyterian) minister of Birnay, 25 December 1703. According to a letter describing the event, he ‘was found in his chamber hanged in his bridle with his hands tied behind his back and the door being bolted within. He had all his life been a man of unblameable life, very much inclined to melancholy and had some time before that communicated to some of his brethren that he was tempted to such a thing and being advised to earnest prayer, he answered that he had prayed till he was weary, but was not heard.’

![]() Listen to Extract 12.8

Listen to Extract 12.8

GD46/17/20, f. 44v

Letter from Peter Fairbairn to Lord Seaforth, 6 March 1801, about the suicide of Provost Inglis of Inverness. At first relatives claimed he had jumped from a bridge, but ‘it is now said he did the deed in his own parlour; that the drowning story was fabricated with a view to get his body privately disposed on’. No reasons were given except a financial loss by a clerk ‘eloping’ with money, but this was not a large sum and the culprit has been apprehended.

![]() Listen to Extract 12.9

Listen to Extract 12.9

CC8/5/29/1, pp. 279-84

‘Quintin Macadam of Craigingillan in Ayrshire was constitutionally affected by insanity, notably in spring and late autumn. Occasionally he had very low spirits and repining gloomy fits. At other times he was very elevated. When the disease was on him he was violent and outrageous to the last degree. … He often spoke of destroying himself and the windows and shutters had to be nailed down to stop him jumping out the window … His eye had a particular appearance which is only remarked in people who are insane. His mind was filled with jealousies and suspicions, which is one of the most common and decisive symptoms of insanity. He was subject to vain and groundless imaginations, & believed that he was despised by everybody. He could not command his attention to any subject, but immediately forgot what was said to him. He was low, gloomy and unhappy, and his inclination to destroy himself at last became the only settled purpose of his mind.’

SPOKEN VERSIONS: Sebastian Bridges, Caroline McWilliams, Hannah Raymond Cox

FURTHER READING: R. A. Houston, Madness and society in eighteenth-century Scotland (Oxford, 2000).

A. Houston, Punishing the dead? Suicide, lordship and community in Britain, 1500-1830 (Oxford, 2010).

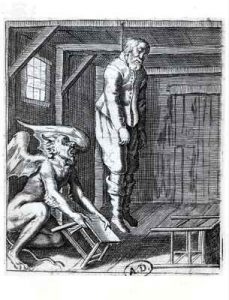

13. Suicide 2. A London coroner’s inquest verdict, 1791

IMAGE: French Artist – Bibliotheque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris, France, engraving. Credit: Bridgeman Art Library / Universal Images Group, Rights Managed / For Education Use Only

NOTE: This image is continental, but it has strong English parallels in showing the common connection in many early modern minds between suicide and the influence of the Devil.

SOURCE: City of London Coroners: Coroners’ Inquests into Suspicious Deaths. London Lives, LMCLIC650040001. Find out more at http://www.londonlives.org/

EXTRACT:

An Inquisition Intended taken for our Sovereign Lord the King at the parish of Saint John within the Borough of Southwark in the County of Surrey on the third day of January in the thirty first Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George the third by the Grace of God of Great Britain France and Ireland King defender of the Faith and So forth before Thomas Sheldon Gentleman Coroner of our said Lord the King of or the City of London and borough of Southwark on view of the Body of a Man whose name is unknown now here lying [..] dead by the Oath of Thomas Lovel, William Cook, William Barton, Thomas Burt, William Harvey, John Ross, John Gilby, John Sincol, Richard George, William Cotton, William Harrison, Henry Smith & Benjamin Hort good and lawful Men of the Borough of Southwark aforesaid who being now here duly chosen sworn and charged to enquire for our said Lord the King when how and in what manner the said man whose name is unknown came to his death say upon there Oath that the said Man whose name is unknown not being of sound mind memory and understanding but lunatic and distracted on the thirty first day of December in the Year aforesaid one end of a certain handkerchief of the value of one penny unto and about a certain Iron bar belonging to a window of a certain Room called the Cage belonging to the [..] house of the parish of Saint Olave within the Borough aforesaid in the County aforesaid and the other end of the said Handkerchief unto and about his own neck then and there did fix tie and fasten by means whereof the said Man whose name is Unknown did then and there hang strangle and suffocate himself of which said hanging strangling and suffocation the said Man whose name is Unknown did then and there die So the Jurors aforesaid upon their Oath aforesaid do say that the said man whose name is unknown not being of sound mind memory and understanding but lunatic and distracted in manner and by the means aforesaid did hang and kill himself In Witness whereof as well the said Coroner, Thomas Lovell the Foreman of the said Jurors on Behalf of himself and his fellows in their presence have to this Inquisition set their hands and seals [..] the Day year and place abovementioned.

Thos Lovell [mark] foreman [of the jury]

City of London Coroners: Coroners’ Inquests into Suspicious Deaths

London Lives

LMCLIC650040001

SPOKEN VERSION: Rosie Beech

FURTHER READING: R. A. Houston, Punishing the dead? Suicide, lordship and community in Britain, 1500-1830 (Oxford, 2010).

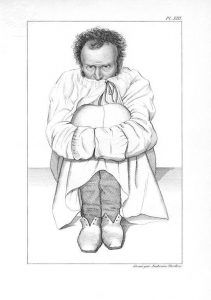

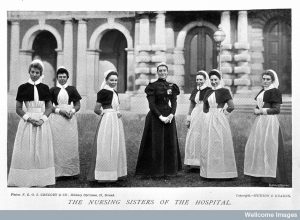

14. Being an asylum patient 1. Cardiff City Asylum regulations, 1919

IMAGE: Psychiatric patient, 19th century. Credit: KING’S COLLEGE LONDON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY / UIG, Rights Managed / For Educational Use Only

SOURCE: Regulation and Instruction Book of the City of Cardiff Mental Hospital (1919).

EXTRACT:

- Every male nurse or servant coming into contact with or passing the Committee of Visitors or Medical Superintendent, the Medical Officers, or the Chaplain shall give a military salute. The nurses are required to stand up if seated.

- They must always bear in mind that the insane are not responsible for their words or actions, and must therefore on no occasion resent either intemperate language or unruly behaviour but exhibit uniform kindness, forbearance and sympathy.

- The patients in general shall not leave their day room to go to bed until between 7.30 pm and 7.45 pm.

- When a patient escapes through inattention or carelessness the nurse in charge will pay a fine.

- No nurse shall be permitted to smoke during the hours of duty.

- No nurse is allowed to bring newspapers on to the ward without the permission of the Superintendent.

- All letters written by patients are to be delivered to the Medical Superintendent.

- When a new patient is admitted he is to have a bath of a temperature of not less than 90 or more than 97 degrees as ascertained by a thermometer.

- No patient can be visited for one month after his admission, unless by special permission of the Medical Superintendent.

- Visitors are prohibited from receiving letters from patients for the post.

- No patient is to be left alone with a visitor, except by special permission of the Medical Superintendent.

- When the weather is cold the patients (exercising) are to be induced to walk quickly, but when the weather is warm they may proceed more leisurely and rest on the garden seats.

- Wherever exercising, the patients are not allowed to pick flowers.

- When walking outside the hospital, the patients are not to be permitted, upon any pretext whatsoever to speak to, or to communicate with persons outside or passing.

- At church they (the nurses) shall behave reverently, join audibly, as far as they are able, in the chanting and singing, encouraging the patients to do likewise.

- In preparing a bath, the cold water is always to be turned on first.

Regulation and Instruction Book of the City of Cardiff Mental Hospital, 1919.

SPOKEN VERSION: Rosie Beech

FURTHER READING: K. Jones, Asylums and after: a revised history of the mental health services from the early 18th century to the 1990s (London, 1993).

Borsay and S. Knight, ‘”Who are these?” Nursing shell-shocked patients in Cardiff during the First World War’, in Borsay, A. and Dale, P. (eds), Mental health nursing: the working lives of paid carers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Manchester, 2015), 75-97.

15. Being an asylum patient 2. Letters from the Royal Edinburgh Hospital, late 19th century

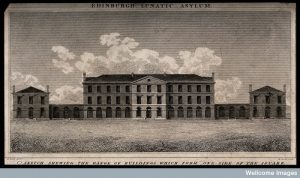

V0012576 Edinburgh Lunatic Asylum, Scotland.

IMAGE: Wellcome Library, London V0012576. Edinburgh Lunatic Asylum, Scotland. Line engraving by R. Scott after R. Reid. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

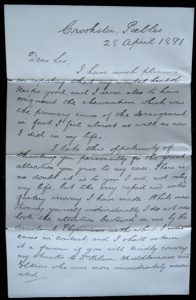

IMAGE: Lothian Health Board Archive, University of Edinburgh, LHB7/51/54, p. 314. James P. to Dr Thomas Clouston 28 April, 1891. Credit: Courtesy of Lothian Health Services Archive, Edinburgh University Library.

SOURCE: Lothian Health Services Collection, Edinburgh University Library. Case Books, LHB7/51. Physician Superintendents of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital collection, GD16.

EXTRACT:

‘You have certainly shown me a great deal of kindness and consideration and I hope you will accept my heartfelt gratitude.’

David H. to Dr Thomas Clouston

‘There is no doubt it is to you I owe, not only my life, but the very rapid and satisfactory recovery I have made.’

James P. to Clouston

‘I venture to think of you as a friend.’

Mary K. to Clouston

‘I have seen as much of Dr Clouston as he has seen of me. I think I have diagnosed him more successfully than he has diagnosed me. Thirty years of unlimited and unchallenged power have made him the quintessence of pompous vanity. Like nearly every man that has risen from the gutter to great wealth and unlimited power he has become at heart an utter tyrant, and the very slightest opposition to his will or even difference of opinion secures his lasting dislike. … I never had five minutes’ continuous and undivided conversation with him since my incarceration. I solemnly state that Dr Clouston never conversed with me five minutes on end, either publicly or privately, at any time in Morningside Asylum. How then can the Doctor know that I am insane? It can’t be from personal observation. He never did give the requisite time. The few minutes he ever saw me were not of the slightest value in forming a correct general inference… Why to an occupied mind thinking of distant and far-away matter it would require a minute or two to adjust yourself to the Doctor’s subjective. Remember it was the initiative which lays always with the Doctor himself. You have been thinking of an abstruse problem in logic or metaphysics. He enters the room determined to test that fellow’s memory or judgement again upon some passing newspaper event familiar to himself. Although you may have given passing notice to it, you did not dwell on it, or it interest you. The Doctor himself is “au fait”. Well your remarks are quite perfunctory, or if you have been deep in other thought, even incoherent. The Doctor stalks off a proud man. It is just as he thought, a growing failure of mental power. A case of G.P. He is always proud of any evidence justifying the retention of a useful and paying patient.’

William B.

‘I suppose the attendants in asylums must be told what is supposed to be wrong with the patients and the attendants in the asylum are not exactly what you would call gentlemen so I feel myself in an extremely painful position.’

Ann C. to Mary

‘Attendant Shaw brutally ill-treated me on many occasions at the East House. He injured my wrist by twisting so that it will never be right again … He always hit me hard in the stomach when he took me into the boot-room, as he did almost daily, and was guilty of innumerable cruelties … I formally complained of him at the time to the Lunacy Board two years ago. Dr Clouston characteristically ignored their remonstrances.’

Daniel B. to Dr Middlemass

‘Fancy a fellow of my age [a 22 year old law student] being thrashed with a walking stick and dragged off suddenly of a morning and pitched head foremost into a bath and held down. A bath does one good but to be kicked like a football and twisted like a wet cloth is too much of a good thing.’

James B. to his mother

‘I was taken out of my own bedroom last night after I was undressed and led by Miss Brown the Matron to others where there was six beds in the room … I did earnestly beg of them to let me remain in my own little room where I was sleeping so soundly … but no I was demanded to lie down even Mrs. McLeod the Housemaid took me by the shoulders and pushed me down on the bed. Well I sobbed and cried aloud but I was told by Mrs. Brown that I would get five minutes to be quiet or she bring down Dr Lennox.’

Wilhelmina G. to her parents

Lothian Health Services Collection, Edinburgh University Library. Physician Superintendents of the Royal Edinburgh Hospital Collection, GD16; Case Books, LHB7/51.

SPOKEN VERSION: Sebastian Bridges, Cameron Rhodes, Ciara Reid

FURTHER READING: A. Beveridge, ‘Voices of the Mad: the patient letters from the Royal Edinburgh Asylum 1873-1908’, Psychological Medicine 27 (1997), 899-908.

Beveridge, ‘Life in the Asylum: Patients’ Letters from Morningside, 1873-1908’, History of Psychiatry 9 (1998), 431-69.

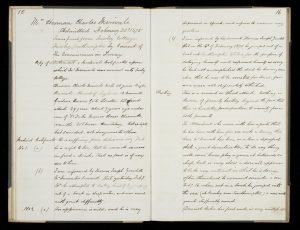

16. Being an asylum patient 3a: Herman Charles Merivale admitted to Ticehurst, 1875

SOURCE: Wellcome Library, London. Ticehurst Case Records, 1875-9, pp. 15-16.

EXTRACT:

Mr Herman Charles Merivale, admitted February 23rd 1875.

Transferred from Fawley Cottage, Fawley, Southampton, by consent of the Commissioners in Lunacy.

Copy of statement and medical statement upon which Mr Merivale was admitted to Fawley Cottage.

Herman Charles Merivale single 36 years barrister. Church of England. 13 Cromwell Gardens, Queens Gate, London. Not first attack. 29 years. About 7 years ago. Under the care of Dr Tuke Manor House Chiswick 12 months. Not know[n]. Hereditary. Not epileptic but suicidal. Not dangerous to others.

Medical certificate no. 1 (a) He is suffering from delusions viz. that he is unfit to live, that he commits excesses in food & drink. That no food is of any use to him.

(b) I am informed by Thomas Joseph Yondell, Mr Merivale’s servant, that yesterday Feby 16th he attempted to destroy himself by jumping out of a boat in deep water, and was saved with great difficulty.

No 2 (a) His appearance is wild and he is very depressed in spirits and refuses to answer any questions.

(b) [repeats evidence of the attempted drowning] and expressed himself as sorry he had not accomplished the deed, he having some idea that he was to be arrested for trial for some cause not definitely stated.

History. This is a second or third attack. Nothing is known of the family history beyond the fact that there is hereditary predisposition to insanity from both parents. The attendant who came with him reports that he has been with him for six weeks & during this time Mr Merivale has been in a low and depressed state & great disinclination to do anything. Will sometimes play a game at billiards or chess, but is very slow and does not appear to take any interest in what he is doing, often threatened to commit suicide [repeats drowning incident]. Does not take his food well, is very restless at [night] …

Ticehurst Case Records, 1875-9, pp. 15-16. Wellcome Library, London

SPOKEN VERSION: Jem Tatar

FURTHER READING: C. MacKenzie, Psychiatry for the Rich: A History of Ticehurst Private Asylum, 1792-1917 (London, 1992).

17. Being an asylum patient 3b: Herman Charles Merivale at Ticehurst, 1875

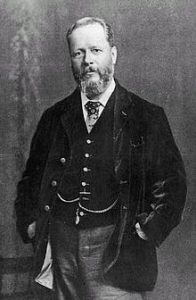

IMAGE: Herman Charles Merivale. Photograph by Elliott & Fry. From the frontispiece to H. C. Merivale, Bar, Stage & Platform (London: Chatto & Windus, 1902).

SOURCE: My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum, by a Sane Patient (London, 1879), 7-8, 40.

![]() Listen to Extract 17.1

Listen to Extract 17.1

EXTRACT:

During these months I had the advantage of living in a castellated mansion, in one of the prettiest parts of England, which I shall hate to my dying day, with a constant variety of attendants, who honoured me by sleeping in my room, sometimes as many as three at a time. I was dying in delirium and prostration … With carriages to take me out for drives, closed upon wet days, open upon fine; with cricket and bowls and archery for the summer, and a pack of harriers to follow across country in the winter; with the head of the establishment, who lived in a sweet little cottage with his family, to give me five o’clock tea on the Sundays; with five refections [meals] a day whereof to partake, with my fellow-lunatics, if so disposed, in my private sitting-room when I could not stand it; with a private chapel for morning prayers or Sunday service. … With little evening parties for whist or music amongst ourselves and a casual conjuror or entertainer from the town to distract us sometimes for an evening. …

I was therefore ‘removed’, half-dying, in a state of semi-consciousness, I can scarcely remember how, to the castellated mansion mentioned in my first chapter. The wrong should have been impossible, of course; but it is possible, and it is law. My liberty, and my very existence as an individual being, had been signed away behind my back. In my weakened perceptions I at first thought that the mansion was an hotel. Left alone in a big room on the first evening, I was puzzled by the entrance of a wild-looking man, who described figures in the air with his hand, to an accompaniment of gibber, ate a pudding with his fingers at the other end of a long table, and retired. My nerve was shaken to its weakest, remember; and I was alone with him! It was not an hotel. It was a lunatic asylum.

My Experiences in a Lunatic Asylum, by a Sane Patient (London, 1879), 7-8, 40.

SPOKEN VERSION: Sebastian Bridges

FURTHER READING: C. MacKenzie, Psychiatry for the Rich: A History of Ticehurst Private Asylum, 1792-1917 (London, 1992).

18. Christian Watt at Aberdeen Royal Mental Asylum, 1877

IMAGE: The Christian Watt Papers

SOURCE: The Christian Watt papers. Edited with an introduction by David Fraser (Edinburgh, 1983), 106-8. A newer, corrected edition is published by Birlinn.

http://www.birlinn.co.uk/The-Christian-Watt-Papers-9781780270722.html

EXTRACT:

The doctor had asked me to go for a rest to Aberdeen Royal Mental Asylum. After a great deal of thought I consented, for something must break. … The world is so unwilling to accept the disturbed mind functions in exactly the same way as the normal one. It is a tremendous problem the mind is trying to cope with; perhaps if I had been less of a thinker and a more dull person it might not have affected me in the same way. … I entered by a small gate set in a high granite dyke, and was admitted. The nurse who gave me a bath commented on how clean I was. We went through endless corridors, and in each section I noticed the door was firmly locked behind us which gave an eerie feeling. … Not even the pangs of sheer hunger could have forced me to eat in the dining room. … Patients were gulping and stomaching their porridge in such a slovenly and distasteful manner. … Then I feigned some excuse to skip dinner, the sister said, ‘If you work in the kitchen you can eat there.’ The Physician-Superintendent was one of the Sibbalds of Balgonie – a well-to-do Fife family. He was a kindly, skeely [skilful] man, genuinely interested in his patients. I spoke with him for an hour, and then I was fixed up with a job in the kitchen. I did not want any of my children to visit me, for it is not the sort of place bairns [children] should see. … Being in the asylum is a terrible stigma. … It seems impossible for the public to be sufficiently educated to the fact that a mental disorder is an illness. Probably the most tragic factor is that the person can be as right as rain one day and tragically sick the next.

The Christian Watt papers. Edited with an introduction by David Fraser (Edinburgh, 1983), 106-8. A newer corrected edition is published by Birlinn.

http://www.birlinn.co.uk/The-Christian-Watt-Papers-9781780270722.html

SPOKEN VERSION: Oli Savage

FURTHER READING: A. Beveridge and F. Watson, ‘The psychiatrist, the historian and The Christian Watt Papers’, History of Psychiatry 17, 2 (2006), 205-21.

19. A ballad about William Frederick Windham, 1862

IMAGE: Broadsheet Ballad: ‘Poor Windham’. Bodleian Library, Oxford. Harding B 11(3115).

SOURCE: Bodleian Library, Oxford. Harding B 11(3115).

EXTRACT:

POOR WINDHAM

Oh! What a silly row there’s been,

And things were very sad then,

They wanted for to make, you know,

A simple lad a madman

Because that he could say ‘mowhow’,

And when the engine started,

He would cut away at one o’clock

Like London to Newmarket.

[chorus]

It is a shame, and what’s their game,

To a madhouse try to send him,

Money, money, that’s the thing

But they won’t get over Windham.

Because he led a jovial life,

And squandered lots of money,

Because he married a buxom wife,

And made things seem quite funny,

Because he was ready to ride,

Whenever the engine started,

Because he used to bowl all night,

Up and down around the Haymarket.

Now Windham has an uncle got,

Some say no man is bolder,

Right good pensions he has got,

A poor discharged old soldier.

He has sons and daughters, too,

At Fullbrigg Hall a grumbling,

And people say their hearts are just,

As hard as Norfolk dumplings.

But never mind, the orphan boy,

Will very soon defeat them,

And noble Cairns will do his best,

Before he’s done to beat them;

He’ll gain the day, mark what I say,

To no madhouse shall they send him,

His enemies all be licked,

They shall not conquer Windham.

Bodleian Library, Harding B 11(3115)

SPOKEN VERSION: Oli Savage

FURTHER READING: Commission de lunatico inquirendo: an inquiry into the state of mind of W.F. Windham, esq., of Fellbrigg Hall, Norfolk (London, 1862).

20. Living with madness 1: an apprentice in danger, 1738

IMAGE: Wellcome Library, London, V0019929. A woman standing at a dressing table while a maidservant laces her stays. Etching by J. Gillray, 1810. Published: H. Humphrey, London (27 St James’s Street), 26 February 1810. Wellcome Library, ICV No 20331. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

SOURCE: Westminster Sessions: Sessions Papers – Justices’ Working Documents. London Lives, LMWJPS654130018. Find out more at http://www.londonlives.org/

EXTRACT

1738. To Nathaniel Blackerby Esqr Chairman of ye Sessions of ye Peace for ye City & Liberty of Westminster and to ye rest of his Majesties Justices of the Peace in Their Quarter Sessions Assembled. The Humble Petition of Bartholomew Hyatt an Apprentice of George Alsop, staymaker

Sheweth

That he has been with his said Master after the manner of an Apprentice above three years during wch. time his said Master has upon very Slight Occasions beat this informant [..] and has at Other times to Gratifie his Passionate Temper attempted to Stab your Petitioner with an Instrumt Us’d in the Staymaking Trade Call’d a Poker & at Other times with a Knife and has put your Petitioner in such Dread of his Life that it has been with the Utmost Difficulty that He has perform’d ye Duty of an Apprentice and as these things have been Repeated often with Little or no Cause given and that the Deportment of his Master in his Neighbourhood has caus’d him to be judg’d a Madman. Your Petition most Humbly represents that He cannot with any Safety Remain in such a Masters Service and as a farther proof of his said Masters Disorder’d Mind Your Petitioner Setts forth that for his pleasure He has Often kept your Petitioner whole Days wth out Permitting him to Eat or to Drink wch. was Obligd to To Submitt to Least his Master should take away his life should he Contradict his will And as Your Petitioner will make it appear to your Worships that his Master has been Guilty of Several Delirious and Madd Actions.

He most Humbly Prays this Honourable Bench to take the Premises into Consideration and that he may be discharged from his said apprenticeship and that his said Master (if your Petitioner proves these Allegations) may be Oblig’d to Restore his friends Such a part of the Mony as They gave his said Master for his apprenticeship which is most Humbly Submitted Etc Etc Etc

Barthow. Hyatt

SPOKEN VERSION: Sebastian Bridges

FURTHER READING: R. A. Houston, Madness and society in eighteenth-century Scotland (Oxford, 2000).

21. Living with madness 2: an insane murderer, 1727

IMAGE: Wellcome Library, London, L0040923. John Totterdale throwing his wife down stairs. Copperplate, 18th Century. From: The new and complete Newgate calendar; or, villany displayed in all its branches … Containing … narratives … of the various executions and other exemplary punishments … in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, from the year 1700 to the present time, vol. 2, By: William Jackson (London: Alexander Hogg, 1795), opposite p. 275. Collection: Rare Books, EPB 30093/B. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

SOURCE: Old Bailey Proceedings: Accounts of Criminal Trials. London Lives, t17270412-21. Find out more at http://www.londonlives.org/

EXTRACT:

Thomas Nash , of Harrow on the Hill , was indicted for the Murder of Mary his Wife , by giving her several Wounds and Bruises with Stones on the Left Side of the Head , on the 5th of this Instant April ; he was a second Time indicted on the Coroner’s Inquest, to both of which Indictments he pleaded not guilty.

Thomas Bond depos’d [testified]. That he found the Deceased in a back Room lying on her Face naked, and with a Door upon her; on the 5th Instant in the Evening afterwards, he met the Prisoner, and asked him where his Wife was? To which he answer’d, he could not tell, she was not come home yet; to which this Deponent reply’d, I believe you have kill’d her, desiring him to come and see her, which he refused: The Court asking the Prisoner if he had any Questions to put to this Deponent, he answered, yes, I desire you would ask him if I owe him any Thing for Milk?

John Page depos’d. When I heard the Prisoner was taken, I went and examined him, and this he confess’d himself to me, My Wife and I quarrell’d on Wednesday and she going out I follow’d her, and by the Way seeing some Stones, I flung ‘em at her; after which she went and lay down in the back House, upon which I followed her, she lay down, and I laid the Door upon her, and then sat upon her for some considerable Time; after this I laid her out, and covered her with Hay, and then left her.

Thomas Watson depos’d. That he was present at his Examination, and saw him sign it in Writing, which was to this Effect, That in Quarrelling, his Wife and Son fell upon him, and one pulled him by the Hair, the other by the Throat, endeavouring to kill him, and he endeavoured to kill them.

Adam Nash , Son to the Prisoner depos’d. That he had been there a Day or two, during which Time there had been some quarrelling, his Father saying, he would lay her on the Fire and this Deponent hinder’d him; but that on Tuesday, (the Day before this Murder was committed) he went away, and left them good Friends.

Leonard Mignard depos’d. That he being a Surgeon was sent for, and searching the Deceased, found two Contusions on the Right side of her Head, near the Temple, the Left Eye and Ear bruised and torn, and her Nose slatted to her Face, which he did believe to be the Cause of her Death.

Eleanor Susmith depos’d. That she had known him for some Years to be a very Crazy Person, not taking his natural Rest, but magotting [cavorting] and rambling like a Mad-man.

Mr. Page further depos’d. That at Times he was besides himself, especially at Spring and Fall, when he was seldom in a Capacity to follow Business.

One of the Jury desired the Question might be asked, Whether he was himself at the Time aforesaid, and at his Examination, which was answered in the Negative.

Mr. Watson further depos’d. That he had known him 13 Years, and that he would sometimes go to his Neighbours Houses and demand such Things as he had occasion for, but where he met with Opposition he came no more, and only tyrannized over them that feared him; his Son said, he was troubled in Mind on Occasion of his being cheated of an Estate by his Brother; he had formerly been a Soldier for fourteen Years, during which Time he had received several dangerous Wounds in the Head, and has still several Marks to shew, which makes it probable those Wound’s might weaken his Intellectuals.