by Katarina Birkedal

Originating as it did from the study of Greco-Roman antiquity, the Visualising War project has always been conscious of the risk that it might end up being too narrowly focused on Western traditions of thinking about and doing war. There are a number of reasons why this is a serious concern, first of which is that such a narrow scope of enquiry, undefined, reiterates pro-Western biases and prejudices both in academia and outside of it. In equating a general, global phenomenon to a specific local iteration – especially when this is unspoken – we risk excluding and othering of all other narratives except those that fit a specific mould, and moreover the naturalisation of those few that do.

A lack of academic interest paid to diverse experiences only furthers the international Western hegemony that already undermines non-Western voices.[i] Many disciplines – Classics and International Relations (IR) among them – show increasing awareness of their Western tilt, with scholars engaging in efforts to decolonise the fields. Nevertheless, there remains a bias, conscious and unconscious, in much of academia. For a project like Visualising War, which is explicitly concerned with understanding and unpicking our habits of narrating war in order to prompt critical reflection on our habits of understanding and doing war, such a narrow focus would be actively counter-productive as well as harmful.

The ‘West’?

There is a lot of received wisdom surrounding the idea of the ‘West,’ so most people know broadly what the term refers to even if they would perhaps struggle with defining it. The concept is held together more by repeated use than any inherent sense, whether geographical, historical, or cultural. Nevertheless, its frequent use lends the notion of a ‘West’ an air of inevitability; it is important to be aware of where the term comes from, and what assumptions it carries.

Kwame Anthony Appiah demonstrates that the idea of the ‘West’ makes no historical sense until the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It was the work of philosophers and academics, who saw the best of European thought as coming from the philosophy and statecraft of the ancient Greeks and Romans. A clear and direct line of descent was established, wherein modern Europe became the sole inheritors of these important and prescient ancient civilisations. This heritage had become muddled in the superstitious Dark Ages, but now the light of rationalism once again shone bright.

The term ‘the West’ itself came about during the age of imperialism, when it was deemed the burden of the ‘enlightened’ ‘West’ to bring this light to the rest of the world. The idea here becomes entangled with the colonial projects that lasted from the late 18th century to well into the 20th. It was Rudyard Kipling who coined the term ‘white man’s burden’ in a poem of the same name; that moral obligation to bring ‘enlightened civilisation’ to ‘savage’ lands [sic].

The putatively bipolar world order of the Cold War further pitted west against east, and ascribed contradictory and inherent ideologies to these. In the the euphoria of the Cold War’s aftermath, the contours of the ‘West’ as bound up with the triumph of reason, liberalism, and democracy becomes clearer. Picking up on Kant’s hope that history moves towards progress,[ii] Francis Fukuyama famously wrote The End of History and the Last Man in 1992, arguing that the ascendancy of ‘Western liberal democracies’ at end of the Cold War was the apotheosis of a process that would see that form of government as the final and ultimate form.[iii] With this achieved, the world might be without war.

The ‘Western way of war’?

This links into the first of three characteristics typically ascribed to ‘Western’ warfare: a just cause, technological superiority, and pitched battles following declared hostilities. I will address all of these in turn below, as briefly and concisely as I dare.

The narrative of ‘Western’ wars as especially justified is bound up with centuries of othering of threatening or thwarted enemies; they had to ‘defend Christendom against the incursions of heathen Moslems [sic] … who were … fanatically determined to convert or extirpate the infidel wherever their swords could reach’,[iv] and so on. Such victors’ tales are then combined with concepts like the idea of just wars to cement this narrative.

The just war tradition is most often traced back to the writings of Thomas Aquinas, who sought to find the conditions under which war could be justified in Christian thought. Drawing on Aristotle, what he concluded was that war ‘is not only a sin; it is also a way of combating sin and, more generally, of preserving the common good’,[v] provided three conditions were met. These were that, first, the war must be waged on the authority of the ruler (however defined); second, the war must be waged for a just cause (that the enemy must be guilty of some evil to be deserving of attack); and, third, that those who wage it must have rightful intentions (i.e. they must intend to do good).[vi] These principles are usefully elaborated into jus ad bellum and jus in bello, which refer respectively to the legitimation of war and the conduct of war.

While scholars like Dr Rory Cox are proving otherwise (identify just war traditions well beyond Greco-Roman antiquity), the just war tradition is primarily regarded as a ‘Western’ tradition, one moreover especially bound up Christianity. Furthermore, in a system of sovereign states, the just war tradition underscored the idea that only the state had legitimate use of force, that only the state could declare war. Likewise, only those soldiers registered in the state’s military could legitimately act and be acted upon in battle.[vii]

For modern ‘Western’ liberal democracies, wars are fought for the purposes of liberation; those who ‘know better’ intervene to remove the chains of oppression and the yoke of injustice, and free the foreign civilians of the terrors of the illiberal, absolutist state. Installing more ‘Western’-style democracies is good, as – per the Democratic Peace Theory – liberal democracies do not go to war with each other. Andrew Williams writes that ‘what distinguishes liberal states from their illiberal counterparts is that they believe quite sincerely in the creation of a better world and that they are exemplars of what that world should look like.’[viii]

Although different words are used, the legacy of the ‘white man’s burden’ is clear to see here.[ix] Moreover, the foundations of this argument are shaky indeed: the Democratic Peace Theory is largely discredited,[x] and the perception that the just war tradition is a purely Christian, ‘Western’ idea is patently false.[xi] As the ‘new wars’ debate in IR has shown,[xii] it is difficult to base any attempt at categorisation on intent, as this is not only entirely subjective, but also subject to historical rewriting. That the intent was to liberate hardly seems relevant to the victims of a bombing round or a drone strike. As John Gray puts it, ‘[liberal] democracies are not only willing to commit acts that when perpetrated by despotic regimes are condemned as signs of barbarism – they are ready to praise these acts as heroic.’[xiii]

The linking of the development of a ‘Western’ way of war with that of the sovereign state is also tenuous. Few clear instances can be cited (such as, famously, Louis XIV), and the theory requires us to to ignore the great impact of private enterprise, hired mercenaries, and the general back-and-forth of state v. non-state controlled militaries.[xiv] Contrary to this typical narrative, it is perhaps the presence of private contractors and companies that characterises the military history of – in particular – Europe; especially in the case of colonial conquest (which, in some cases,[xv] is curiously left out of the story completely).[xvi]

The second posited characteristic of the ‘Western’ way of war is technological superiority. This narrative is entangled with that of the development first of the sovereign state, and then of citizen participation in state affairs through industrialisation and capitalism.[xvii] The story here goes that the consolidation of legitimate force under a single, state-controlled citizen army led to greater technological innovation due to the mobilisation of the state’s considerable human and financial resources.[xviii] War changed with the developments of industrialisation, so that the soldiers manning the machine gun became workers, and the military was broken into systems of organisation and information.[xix] By the time of the First World War, conflict had developed to the point of a total war – beyond attrition to annihilation – where the goal was to drain the enemy state of resources into a total collapse, before they could do the same to you.[xx]

The development of firearm technology combined with the state’s enlistment of soldiers led to a greater need for uniformity in appearance and behaviour within the army.[xxi] Military drills combined with parade ceremony, rote learning, and science applicable to gunnery was taught to produce disciplined, rational, and ‘improved’ soldiers for the state.[xxii] Firing the musket was broken down into mechanical drill exercises, communicated through instruction manuals.[xxiii]

Later technological developments furthered the need for the soldier to be optimised for the performance of the weapon. The arrival of the machine gun meant that it was ‘imperative not only to wield the machine, but to embody it as well.’ The centrality of technological superiority to ‘Western’ warfare can perhaps best be summed up by Hilaire Belloc’s famous words: ‘Whatever happens, we have got / The Maxim gun, and they have not.’[xxiv]

The influence of Enlightenment thinking is visible here; the creation of ‘improved’ soldiers through state discipline and rote learning makes sense in the context of a culture obsessed with rational and objective scientific thinking. This connection between the civic spirit and the disciplined soldier, some argue, is inherited from the Romans.[xxv] From the Scientific Revolution came the idea that science was a ‘Western’ virtue, and another heritage from the ancient Greek and Romans;[xxvi] the rational ‘Western’ man would use science to understand and control nature,[xxvii] including all who were not white men.

Furthermore, the attachment of the soldier and the mechanisation and technology of the machine gun makes sense in the context of the introduction of the gender binary as something supposedly biologically inherent, which placed white men at the top of a constructed hierarchy, with white women between them and everyone else. [xxviii] It was thus the white, male body that was the deciding factor in warfare; and in the case of the machine gun, the eventual fusing of the weapon with the masculine.[xxix]

This fusing of the mechanical and the masculine was later picked up on by the Futurists, who glorified the speed made possible by technology, and who further linked technological advancements with militarism.[xxx] The importance of speed is another recurring feature of technologically driven warfare, wherein time ‘has become a new medium for delivering injury.’[xxxi] Whether through practice for the inevitable air strike,[xxxii] or through the suddenness of ‘instantaneous nuclear annihilation’, time and violence become intermixed so that ‘violence blurs into terror, is fixed at the speed of light’.[xxxiii] Speed remains one of the proposed defining features of ‘Western’ warfare.[xxxiv]

Given the speed at which destruction could arrive, and the range from which it could be delivered, the need for oversight grew, until sight and surveillance, too, became weapons.[xxxv] The idea of the Panopticon is useful, here: a prison built on system of surveillance that allows one person to observe many, who cannot observe each other.[xxxvi] For the purposes of warfare, it translates to a need to observe not only the battlefield, but all elements of society that might feed into a battlefield, such as – post 9/11 – ‘flight schools, airports, and … practically every nook, cranny, and cave of Afghanistan.’[xxxvii]

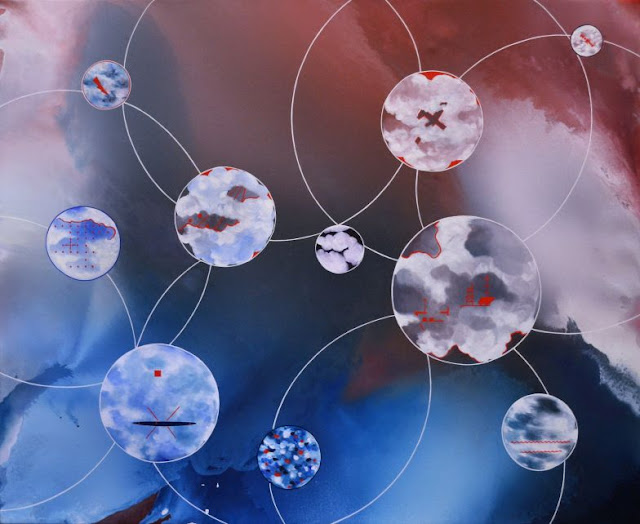

When violence can happen at such speed, any risk is deemed unacceptable, leading to the need to ‘foresee and control the future consequences of human action’.[xxxviii] Yee-Kuang Heng argues that ‘the idea of linear progress, certainty, controllability and security of early modernity has collapsed, replaced by reflexive fear of undesirable risks.’[xxxix] As Antoine Bousquet demonstrates, methods of warfare mimic the current scientific paradigm; from clockwork mechanisation that prioritised linear deployment and rigid drills, to current ‘chaoplexic’ warfare that prioritises non-linear, self-organising networks of information to best combat a chaotic, many-headed threat.[xl]

Rather than bringing stability to the ‘West,’ the end of the Cold War brought the terror of the ‘unspecified enemy’;[xli]this, and later the shock of 9/11, prompted the latest shift in the ‘Western’ way of war, wherein ‘the immediacy of the catastrophe, the immediacy of disaster, could not happen again – because it would always already have been premediated.’[xlii] Here we arrive at the intersection between the first and second proposed characteristic of ‘Western’ warfare: that of just cause and technological superiority. James Der Derian calls this ‘virtuous war:’ ‘the technical capacity and ethical imperative to threaten and, if necessary, actualise violence from a distance – with no or minimal casualties.’[xliii] Here, the desire to technologically master chaos through future (visualised) prediction subordinates ‘history, experience, intuition, and other human traits … to scripted strategies and technological artifice, in which worst-case scenarios produce the future they claim only to anticipate, in which the tail wags the dog.’[xliv]

Like the first narrative of ‘Western’ warfare, the one of military superiority through technological superiority also collapses under scrutiny. Firstly, there is nothing particularly ‘Western’ about technological innovation in warfare; the two have been interwoven from the start,[xlv] and some of history’s most decisive new technologies – such as the stirrup[xlvi]and the chariot – were not ‘Western’. Indeed, for most of history, it was not the ‘West’ that demonstrated its military superiority, but Central Asia.[xlvii]

Moreover, the association of technological development with ‘Western’ military culture – especially when adding the element of drill and discipline – ignores the great diversity of cultures within the ‘West.’[xlviii] Further, as history repeatedly demonstrates, the presence of new technology does not guarantee victory and military superiority.[xlix]Arguably, if there is anything particularly ‘Western’ about the use of technology in war, it is the over-reliance on it.[l]

The third typical narrative posits pitched, open, decisive battles following official declarations of hostility as characteristic of ‘Western’ warfare. According to Victor Davis Hanson, this is a feature that can be traced directly back to the ancient Greeks, who fought with heavy hoplite infantry in tight, linear formations.[li] If our sources are to be relied on (and we ought to take their idealisation with a pinch of salt, as Owen Rees and Roel Konijnendijk explain on one of our podcasts), these battles were brief, intense, and pitched, declared and consented to, and enacted in such a way as to spare noncombatants and property;[lii] as such, they also marked a sharp difference from sneaky, tricksy, and deceitful warfare.[liii] Moreover, they were fought by citizens for civic purposes.[liv]

Indeed, the Greek fought according to agreed-upon conventions that respected truces and cultural events like the Olympics, declared that noncombatants should not be the primary targets, limited the use of missile weaponry, dictated the conduct of victors towards prisoners and the defeated, and dictated that war should be declared and battle begun by official ceremony.[lv] Or so later, selective and romanticising analyses of our ancient sources suggest.

For Hanson – whose arguments are both influential and controversial – this manner of fighting, face to face on foot and with great and deliberate lethality in a delineated setting, endured to become the emblematic ‘Western’ way of war.[lvi]These characteristics – wars declared and waged according to rules, battles fought with excessive violence, for expedience and political purpose, by soldiers – do resonate with many qualities ascribed to modern ‘Western’ warfare, as well as definitions of war more broadly.

In her elaboration of the difference between ‘old’ and ‘new’ wars, Mary Kaldor references many characteristics of ‘Western’ wars in her description of ‘old’ ones (including some mentioned above); of these, the view of war as a means of enforcing state interest, the development of ‘rational’ rules for the conduct of war, and the willingness to use overwhelming force in delineated, decisive battles (otherwise to be avoided)[lvii] most clearly mirror those characteristics of Greek warfare Hanson emphasises. She makes frequent use of Clausewitz, for whom war is the ‘instrument of political change’,[lviii] with ‘no logical limit’[lix] on the violence needed to achieve this. And indeed, for those of Clausewitz’s time, battle was ‘butchery,’ perpetrated by lines and upon lines of soldiers in formation, meeting each other upon the battlefield.[lx]

However, whilst the Renaissance did see a conscious effort to imitate classical warfare,[lxi] that is the limit of the direct line of decent of ‘Western’ warfare from the ancient Greek model. As Lynn points out, already with imperial Rome the line begins to waver.[lxii] Moreover, as Everett Wheeler notes, although Hanson is skilled at bringing to life the gruesome details of hoplite warfare, he cherry picks aspects to suit his theory, whilst ignoring those that contradict it.[lxiii] In so doing, Hanson skips over the effect of the efforts of the later Panhellenists to enshrine the warfare of their ancestors in notions of chivalry and honour, as well as the degree to which these sorts of pitched battles are not at all a special Greek form of warfare.[lxiv] As Roel Konijnendijk argues, the ancient Greeks were very aware of the high risk of such battles, and the role chance played in them, and were not at all opposed to more tricksy means of warring.[lxv]

Nevertheless, these assumptions are reflected in many definitions of war, which require a declaration, the participants to be states (with rational state interests), and/or a certain number of fatalities to qualify as such.[lxvi] These strict criteria – along with sharp delineation between domestic, sub-state, and international conflicts – have contributed to a ‘compartmentalisation’ of research that limits our understanding of conflict.[lxvii]

Some of the enduring nature of this traditional definition of warfare can perhaps be linked to the Victorian decision to continue to depict battles as such, even when these depictions no longer corresponded to the reality of battle. Ramey Mize argues that before the linking of masculinity with machines, there was a prevalent concern that such means of waging war lacked glory and undermined the idea of the soldier-hero.[lxviii] As a consequence, the Victorian public was presented with images of victorious, white British heroes, instead of the clusters of soldiers gathered around the machine gun: the true ‘hero’ of colonial conquest.

Whilst accounts of ‘Western’ warfare often overlook these wars of colonial conquest,[lxix] colonial conquest could arguably be the closest to a distinctly ‘Western’ way of war: a messy mix of private and state forces and interests, identity-based political justifications, excessive violence and the use of concentration camps and genocide in population subjugation and control, and tactics aimed at establishing asymmetry in battles, frequently through the use of technology that facilitates distance on the part of the ‘Western’ soldier. Perhaps, if the very idea of the ‘West’ is a construct of imperial ideology, then the brute force of imperialism is the closest we can get to a ‘Western way of war.’

Likewise, where modern ‘Western’ warfare involves drone strikes, covert operations and infiltrations, and night-time ambushes of settlements, it is arguably closer to that tricksy and deceitful form of warfare that Hanson is so keen to separate from.

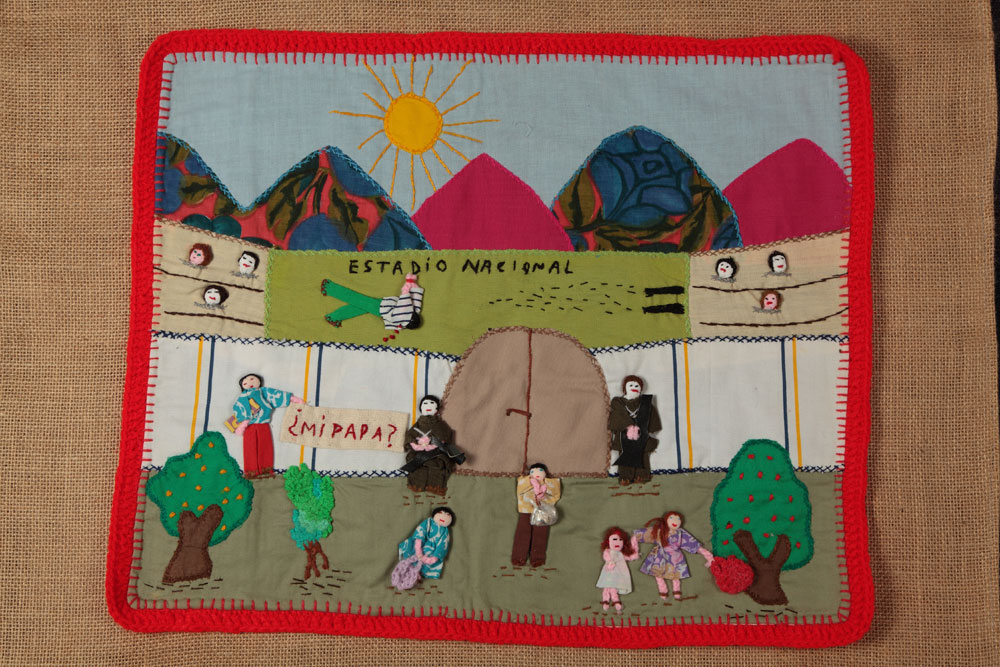

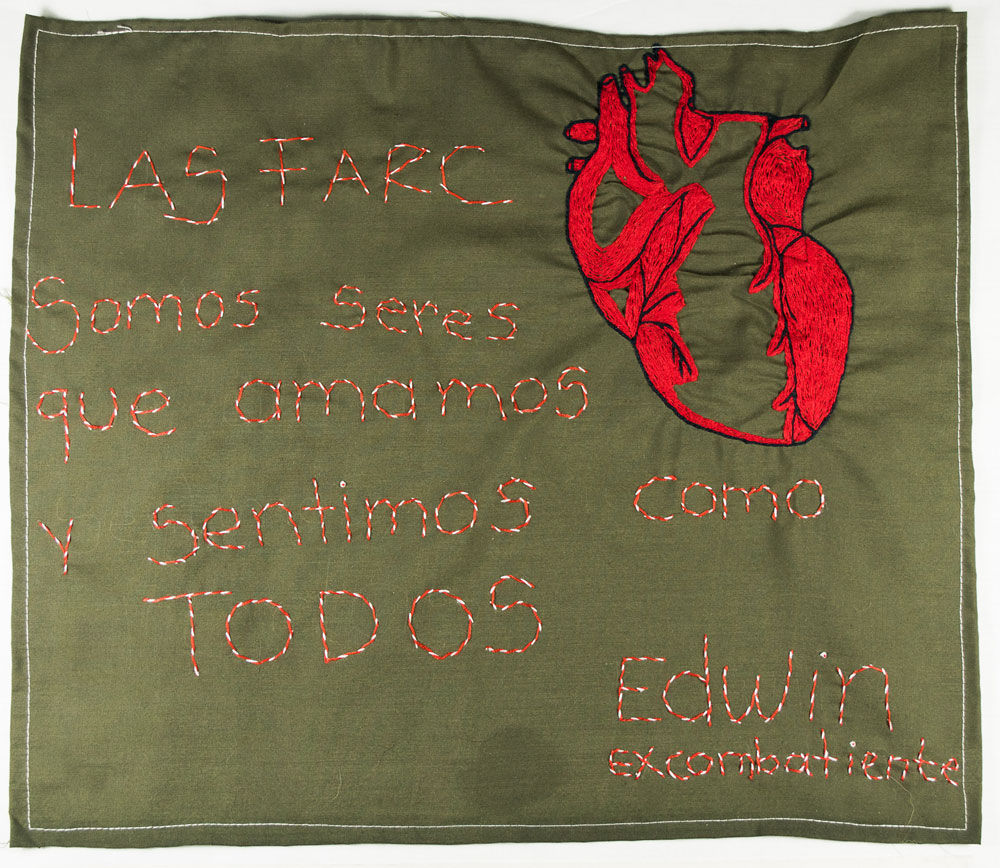

I should note, however, that can we run into problems here so long as wars need an element of reciprocity in order to be wars; otherwise we might enter the territory of massacres, genocides, and occupations.[lxx] As established in previous thought pieces, it is important not to paint such forms of violence with the brushstrokes of war, lest we – wittingly or unwittingly – legitimise the re-writing and forgetting of atrocities and traumas.

The point I want to make is that most of the criteria associated with a ‘Western’ sort of warfare are too general to be any sort of criteria at all. This is not to say that there is no such thing as a ‘Western’ way of war, but rather that most attempts at defining it come from an inside perspective that relies on what the ‘West’ values about itself; such perspectives are rarely accurate and always biased.

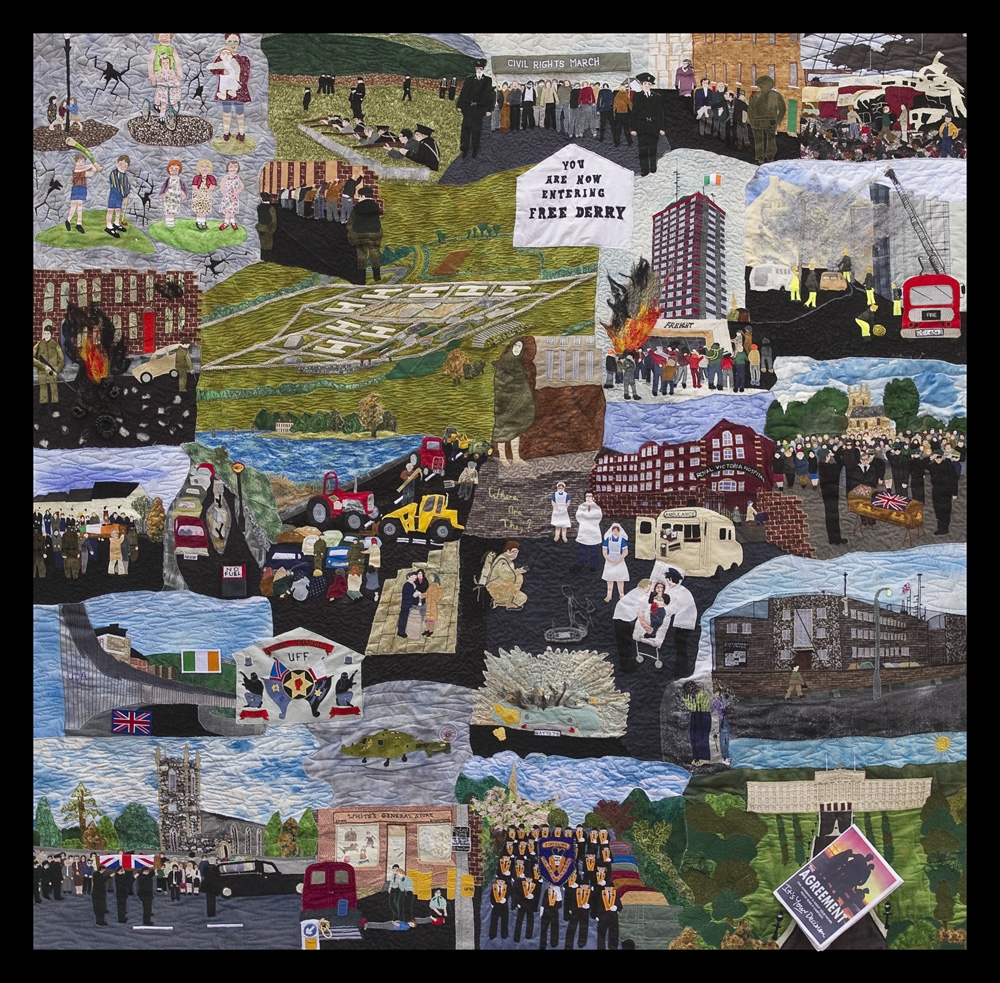

As Hew Strachan and Sibylle Scheipers put it, ‘[categorisation] rides roughshod over difference’;[lxxi] in positing a particular ‘Western’ way of doing war, a lot of nuance and complexity becomes lost, a lot of unknowns are glossed over in the name of continuity, and a lot of (often problematic) ideals are perpetuated. Even where we know the shape and numbers of a conflict, we cannot be sure of their accuracy, as only some lives tend to be considered worth grieving in a society, so that the total loss is uncertain.[lxxii] Furthermore, whose experiences of war do we listen to? What do we do with narratives of war when they don’t fit with our thinking on it? And are these experience-based narratives ever unmediated by pre-existing ways of talking about war?[lxxiii] As Christine Sylvester puts it, war is a ‘transhistorical and transcultural social institution’,[lxxiv] one that we are all part of in different and particular ways; further, it is ‘a chameleon […] able to adapt with apparent effortless ease to altered circumstances.’[lxxv] There is, perhaps, too much of chaos in war to posit any particular way of war, ‘Western’ or not.

I am not seeking to make a facile argument that the ‘West’ and the ‘Western way of war’ do not exist, and thus the concepts are obsolete and should not be engaged with. Rather, I want to suggest that these concepts only make sense when viewed in the contexts of colonialism and whiteness. As such, it is important to tackle the stories we tell of ‘Western’ wars, to unpack how such narratives further a particular set of values. The Visualising War project’s interest in ‘Western’ ways of war revolves around this deconstructive focus: in putting narratives and habits of visualising war under the microscope, we aim to raise awareness of their impacts on how future wars might be conceived, understood, fought, or prevented.

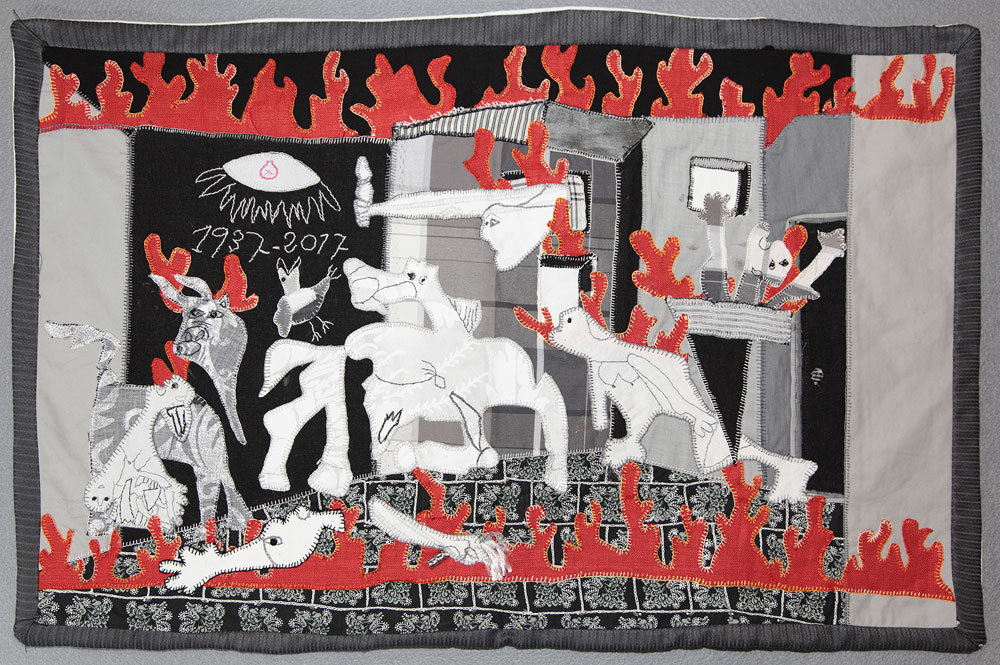

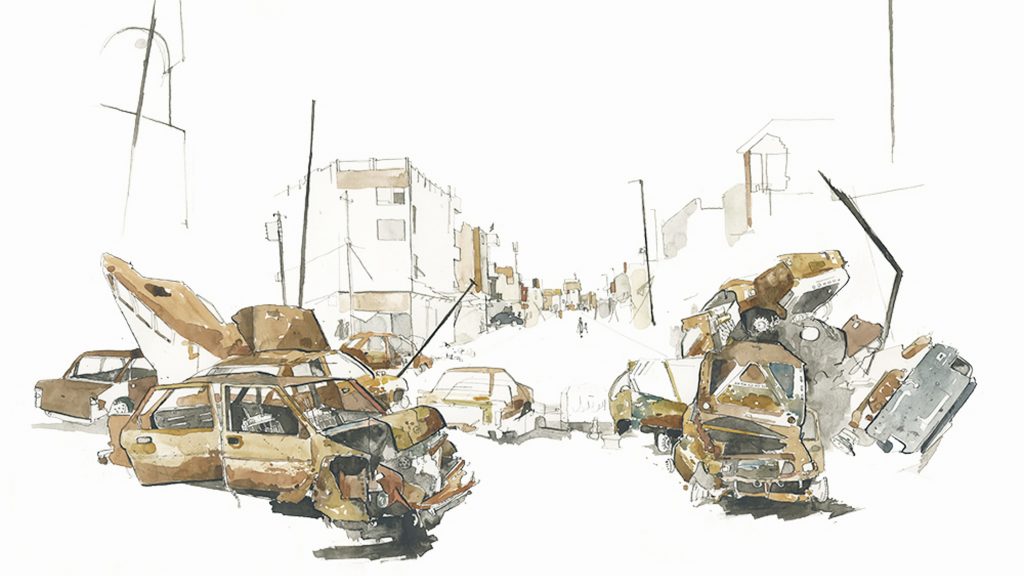

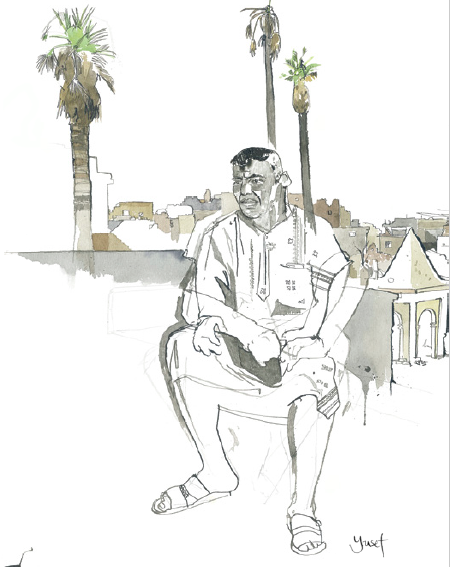

The Visualising War project is an ambitious one that seeks to understand and pick apart ways of imagining, telling, and thinking about war from across history, across the world. Associated with the project are researchers like Laura Mills, who investigates martial politics in the everyday through veteran art and the Invictus Games; Leshu Torchin, who has written on the witnessing of the Armenian Genocide in film; and Rory Cox, who has expanded on the history of the just war tradition before Thomas Aquinas, including the ethics of war in ancient Egypt. Through our podcast so far we have spoken to, inter alios, Iraqi artist Rana Ibrahim about women’s use of art to communicate their experience of war and displacement; theatre group NMT Automatics about the use of theatre in (re)communicating war stories; Omar Mohammed (aka Mosul Eye) about the power of blogs to visualise conflict as it unfolds; journalists based in Afghanistan about the intersection between journalism, conflict and peace reporting; and Lady Lucy French of the Never Such Innocence project about the voices of children in conflict. For the future, the intention is to work towards greater diversity in focus and participants, across all aspects of the project.

Postdoctoral Researcher Katarina Birkedal obtained her PhD from the University of St Andrews in 2019. She works on gendered experiences of conflict, manifestations of militarism in popular culture, and the aesthetics of depicted violence. She is using her experience of working across different disciplines and art forms to bring together members of the Visualising War research group who work in very different fields to enhance the project’s interdisciplinarity.

[i] On academic complicity and exclusionary practice, see e.g. Alison Howell, ‘Forget “Militarization”: Race, Disability and the “martial Politics” of the Police and of the University’, International Feminist Journal of Politics 20, no. 2 (2018): 117–36; Marysia Zalewski, Feminist International Relations: Exquisite Corpse, Interventions (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013).

[ii] Fred Halliday, ‘The Potentials of Enlightenment’, Review of International Studies 25, no. Special Issue: The Interregnum: Controversies in World Politics 1989-1999 (1999): 105–25.

[iii] See also Francis Fukuyama, ‘The End of History?’, The National Interest 16 (1989): 3–18.

[iv] Michael Howard, War in European History, Updated edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 5.

[v] Chris Brown, Terry Nardin, and Nicholas Rengger, eds., International Relations in Political Thought: Texts from the Ancient Greeks to the First World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 183.

[vi] Brown, Nardin, and Rengger, 184–85.

[vii] Mary Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, 2nd Edition (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2006), 19–20.

[viii] Andrew Williams, Liberalism and War: The Victors and the Vanquished (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 5.

[ix] Williams, 35.

[x] Colin Gray, ‘Clausewitz Rules, OK?’, Review of International Studies 25, no. Special Issue: The Interregnum: Controversies in World Politics 1989-1999 (1999): 161–82.

[xi] Rory Cox, ‘Expanding the History of the Just War: The Ethics of War in Ancient Egypt’, International Studies Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2017): 371–84.

[xii] Mats Berdal, ‘The “New Wars” Thesis Revisited’, in The Changing Character of War, ed. Sibylle Scheipers and Hew Strachan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 109–33; Christine Sylvester, War as Experience: Contributions from International Relations and Feminist Analysis (London: Routledge, 2013), 24.

[xiii] John Gray, Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 270.

[xiv] Parrott, ‘Had a Distinct Template for a “Western Way of War” Been Established before 1800?’, 56–59.

[xv] e.g. Keegan, A History of Warfare; Howard, War in European History.

[xvi] Parrott, ‘Had a Distinct Template for a “Western Way of War” Been Established before 1800?’, 59.

[xvii] Christopher Coker, Barbarous Philosophers: Reflections on the Nature of War from Heraclitus to Heisenberg (London: Hurst and Company, 2010), 56–57.

[xviii] David Parrott, ‘Had a Distinct Template for a “Western Way of War” Been Established before 1800?’, in The Changing Character of War, ed. Hew Strachan and Sibylle Scheipers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 49–50.

[xix] Christopher Coker, The Future of War: The Re-Enchantment of War in the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 17,34.

[xx] Howard, War in European History, 114.

[xxi] Keegan, A History of Warfare, 342–44.

[xxii] Keegan, 14-15,342-344.

[xxiii] Christopher Coker, Warrior Geeks: How 21st Century Technology Is Changing the Way We Fight and Think About War (London: Hurst and Company, 2013), 80.

[xxiv] From his 1898 poem ‘The Modern Traveller.’ CW: explicit period-typical racism.

[xxv] John A Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture (New York: Basic, 2008), 14.

[xxvi] Lynn, 14.

[xxvii] Antoine Bousquet, The Scientific Way of Warfare: Order and Chaos on the Battlefields of Modernity (London: Hurst and Company, 2009), 13–21.

[xxviii] See e.g. Alice Domurat Dreger, Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000); Anne Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality (New York: Basic, 2000); Londa Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1993).

[xxix] Ramey Mize, ‘“Whatever Happens, We Have Got, the Maxim, and They Have Not”: The Conspicuous Absence of Machine Guns in British Imperialist Imagery’, The Rutgers Art Review: The Journal of Graduate Research in Art History 33/34 (2018): 43–65.

[xxx] Zeev Sternhell, Mario Sznajder, and Maia Asheri, The Birth of Fascist Ideology: From Cultural Rebellion to Political Revolution, trans. David Maisel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989), 28–29.

[xxxi] Paul K. Saint-Amour, Tense Future: Modernism, Total War, Encyclopedic Form (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 7.

[xxxii] Saint-Amour, 7.

[xxxiii] James Der Derian, ‘Spy versus Spy: The Intertextual Power of International Intrigue’, in International/Intertextual Relations: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Toronto: Lexington Books, 1989), 163–87.

[xxxiv] RUSI, Western Way of War, n.d., https://rusi.org/podcast-series/western-way-war-podcasts.

[xxxv] Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller (London: Verso, 1989), 3,70; Derek Gregory, ‘From a View to a Kill: Drones and Late Modern War’, Theory, Culture & Society 28, no. 7–8 (2011): 188–215.

[xxxvi] Jenny Edkins, Poststructuralism and International Relations: Bringing the Political Back In (London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1999), 50; See Michel Foucault, Les Mots et Les Choses: Une Archéologie Des Sciences Humaines (Paris: Gallimard, 1966).

[xxxvii] James Der Derian, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network, 2nd edition (Oxford: Westview Press, 2009), 232.

[xxxviii] Ulrich Beck, World Risk Society (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1999), 3–4.

[xxxix] Yee-Kuang Heng, War as Risk Management: Strategy and Conflict in an Age of Globalised Risks (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006), 32.

[xl] Bousquet, The Scientific Way of Warfare: Order and Chaos on the Battlefields of Modernity, 30–35.

[xli] Qua Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schitzophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 491.

[xlii] Richard Grusin, Premediation: Affect and Mediality after 9/11 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 12.

[xliii] Der Derian, Virtuous War: Mapping the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment Network, xxxi.

[xliv] Der Derian, 218.

[xlv] Antoine Bousquet, ‘Chaoplexic Warfare or the Future of Military Organization’, International Affairs 84, no. 5 (2008): 915–29.

[xlvi] Also: Albert E Dien, ‘The Stirrup and Its Effect on Chinese Military History’, Ars Orientalis 16 (1986): 33–56.

[xlvii] Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture, 22.

[xlviii] Parrott, 54–55.

[xlix] Parrott, ‘Had a Distinct Template for a “Western Way of War” Been Established before 1800?’, 53.

[l] RUSI.

[li] Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture, 3. One of our recent podcasts discusses the later idealisation of Greek pitched battles, which overemphasised their military and historical significance: https://www.buzzsprout.com/1717787/9519585.

[lii] Everett L Wheeler, ‘Reviewed Work(s): The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece by Victor Davis Hanson’, The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 21, no. 1 (1990): 122–25.

[liii] Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture, 4.

[liv] Lynn, 10–12.

[lv] Lynn, 4–5.

[lvi] Hanson (2001), cited in Lynn, 13–14.

[lvii] Kaldor, New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era, 17,19,25-27.

[lviii] Christopher Coker, War and the 20th Century: A Study of War and Modern Consciousness (London: Brassey’s, 1994), 4.

[lix] Clausewitz ([1832] 1976), cited in Laura Sjoberg, Gendering Global Conflict: Towards a Feminist Theory of War (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 16.

[lx] Keegan, A History of Warfare, 9.

[lxi] Lynn, Battle: A History of Combat and Culture, 18.

[lxii] Lynn, 15.

[lxiii] Wheeler, ‘Reviewed Work(s): The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece by Victor Davis Hanson’. Interestingly, he instead puts forward two Homeric ways of Greek warfare: that of Achilles –‘the advocacy of chivalry, face-to-face confrontation, open battle, and use of force’ – and that of Odysseus – ‘a belief in the superiority of trickery, deceit, indirect means, and the avoidance of battle, although not the denial of the use of force or battle if advantageous.’

[lxiv] Wheeler.

[lxv] Roel Konijnendijk, ‘Risk, Chance and Danger in Classical Greek Writing on Battle’, Journal of Ancient History 8, no. 2 (2020): 175–86.

[lxvi] Laura Sjoberg, Gender, War, and Conflict (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014), 9.

[lxvii] Roger Mac Ginty and Andrew Williams, Conflict and Development (Abingdon: Routledge, 2009), 16.

[lxviii] Mize, ‘“Whatever Happens, We Have Got, the Maxim, and They Have Not”: The Conspicuous Absence of Machine Guns in British Imperialist Imagery’.

[lxix] Berdal, ‘The “New Wars” Thesis Revisited’, 113–16.

[lxx] Hew Strachan and Sibylle Scheipers, ‘Introduction: The Changing Character of War’, in The Changing Character of War, ed. Hew Strachan and Sibylle Scheipers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 7.

[lxxi] Strachan and Scheipers, 5.

[lxxii] See Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2006).

[lxxiii] See e.g. Sylvester, War as Experience: Contributions from International Relations and Feminist Analysis, 45–49.

[lxxiv] Sylvester, 5.

[lxxv] Gray, ‘Clausewitz Rules, OK?’