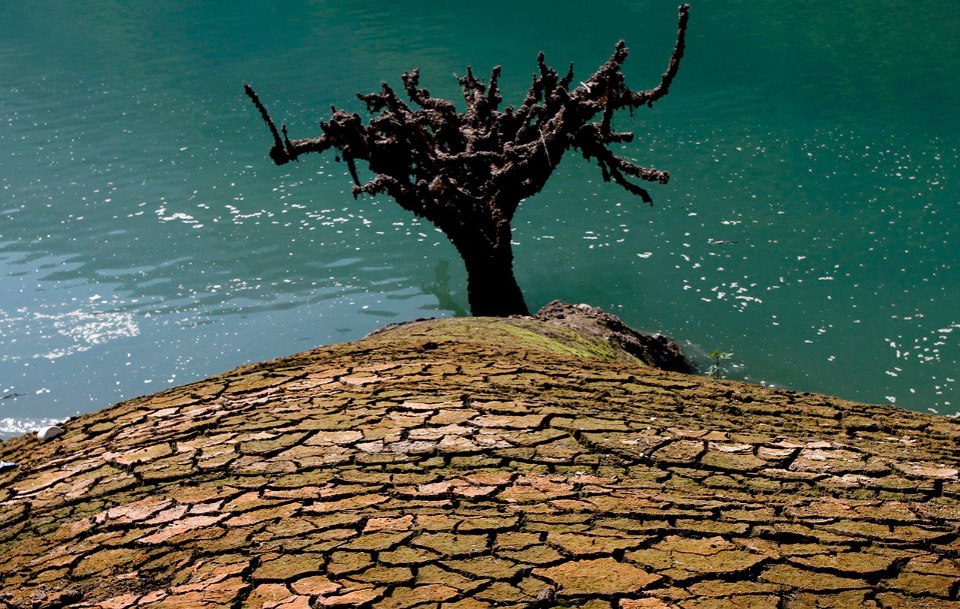

Lake Perucac, photographed by Dijana Muminovic. Due to an error at the nearby dam in 2010, during maintenance work on the Bajina Basta hydroelectric power station, the lake dried revealing the bones of hundreds of people killed during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War. The lake, 54 km long and 1,100 wide is now considered to be the largest mass grave in Europe. The Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia and Herzegovina began a search with volunteers. The image on the right features Admir Sabanovic, searching for his father who was killed in 1992 during the attack of Visegrad. Sabanovic’s father was found two months later in a forest, an hour away from the lake.

Dijana Muminovic is a Bosnian-American documentary photographer. As she recounts in this podcast episode, she was 9 years old when the Bosnian War broke out in April 1992, and her childhood was dominated by the conflict. She vividly remembers the day it started: out picking flowers, she heard the first siren, followed by a sound that she would quickly learn was the noise of a bomb; and she ran to hide for the first time in the family’s basement. That routine became part of her childhood for the next four years: lots of time hiding in bomb shelters, and coping without electricity or water, with shortages of food, and with constant fear and anxiety, while dreaming of peace.

Dijana grew up in Zenica, an industrial town about 70km north of Sarajevo. Unlike the capital city, it was not a key target during the war; in fact, Zenica became a place to which people from other towns and villages fled. People whose homes had been bombed or burnt, and in particular many Bosnian Muslims who had become targets of ethnic cleansing. Dijana remembers her school becoming a shelter overnight, with the gym crammed full of people. As she puts it:

‘That was my first introduction to what it meant to be a refugee. And for me, it meant that people came with nothing, having left everything they had. And they will probably never go back to their homes again…’

Dijana Muminovic, speaking on the Visualising War and Peace podcast

Dijana’s own father was Muslim, while her mother was Catholic. They eventually became refugees themselves, moving to the US in 1997. Some years later, shortly after graduating from university and starting out as a documentary photographer, Dijana was commissioned to develop a photographic project that would help explain the presence of so many Bosnians in her adopted part of America, near Kentucky. That project took her back to Bosnia and set her on a journey to document the ongoing process of exhuming and identifying victims of the Bosnian genocide. Her award-winning series of photographs entitled Aftermath focuses particularly on the exhumation of bodies from Lake Perucac, which borders Serbia and Bosnia-and-Herzegovina, where approximately 800 bodies were thrown during the Bosnian war. One of Dijana’s photos was chosen by the journalist and author Christina Lamb as the front cover of her book, Our Bodies, Their Battlefield: what war does to women.

In our podcast conversation, Dijana talks about the natural beauty of Lake Perucac, and how that beauty contrasts with the horror of what was recovered from it. She captures this paradox in several of her photographs, including the contrasting images of the tree on the lake’s shore shown above: in one, the ground is undisturbed and everything looks idyllic; in the other, the sombre task of digging has begun, shattering the illusion of peace. This paradox is evident also in the two images below. The stunning landscape on the left draws the viewer in, but closer inspection reveals four volunteers digging in the foreground – and their work disrupts the tranquility of the shot, just as they disturb the earth itself. Sunshine illuminates the far shore of the lake in the image on the right, but it also picks out colourful flags, which mark the presence of bones in the exposed lake bed at the front of the shot. Horror amid beauty; traces of war and genocide in an otherwise lovely landscape.

Volunteers help the Missing Persons Institute of Bosnia and Herzegovina to exhume bodies from Lake Perucac, which dried up due to an error at a hydropower station. Photography by Dijana Muminovic.

Dijana’s photographs also capture the physical and emotional labour of exhumation and identification for the volunteers involved. In one photo, we can see four people wearing raincoats digging in the drizzle. A dog is prancing around at the edge of the water, and its playfulness offsets the diggers’ sombre task. Three are bent over while the fourth takes a break and stands watchfully by, waiting to see what gets unearthed. This is just the beginning of a slow, laborious process of uncovering crimes against humanity.

In other photos we can see more of the work done by volunteers to bring closure to families who lost loved ones during the war. On the left, Dijana has captured the sombre interactions between three men who have just dug up a victim’s passport; and in another, a forensic pathologist is standing with her hands on her hips as she braces herself to start processing more jaw bones and broken skulls on her lab table. Together, these photographs capture just how much work is done by so many different people in processing the aftermath of conflict. Some of the volunteers are searching for their own family members.

Left: Goran Micic, left, shows an ID to Admir Sabanovic, right, that was found in a pit while searching for the remains of Sabanovic’s father who was killed in 1992. With the help of few friends, the MPI, and the ICMP, Sabanovic was able to find bones of his father. The ID belonged to the man found with Sabanovic’s father; the father of Adisa Karisik who also volunteered at Lake Perućac.

Right: Forensic Anthropologist, Dragana Vucetic, at the Tuzla Identification Coordination Division (ICD) July 9, 2010. The ICMP has helped exhuming bodies from Lake Perućac.

Some of Dijana’s photographs are quite ‘documentary’ in the sense that they capture a snapshot in time – a boy looking at the flower he is about to lay in a commemoration ceremony, or three women whose raw grief is etched on their faces in three very different ways. Others are more ‘artfully constructed’ – for instance, using reflections or unusual lighting to add meaning to an image. In all her photography, Dijana is conscious of two driving motivations: the importance of documenting what has happened, and the value of helping viewers to connect emotionally with the victims of conflict and killing. These motivations are at the heart of some other work she has been doing, capturing the stories of some of the 20,000-50,000 women survivors of war rape in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Through her work, Dijana underlines the power of sensitive, human-centred photography in helping us visualise many different aspects of war’s aftermath.

You can read more about Dijana’s work on her website. We have also featured some of her photographic work that has been inspired by her own experiences as a refugee on our Visualising Forced Migration project website. You can listen to Dijana tell her own story in the podcast below.