This guest post has been contributed by Pauline Zerla, a doctoral researcher in the department of War Studies at King’s College London. Her research mostly focuses on peacebuilding, trauma and mental health in conflict, and veterans’ return from war. Prior to her doctoral studies, she spent a decade working on project design and management in fragile and conflict-affected states including the DRC, CAR, Nigeria, and Somalia.

‘Every day, we miss what we have lost.’

In Spring 2022, my colleague Miller Mokpidie and I travelled to Eastern Central African Republic (hereafter CAR) to learn how women see the impact of war on their lives and on their communities. We sat with three groups of women who had survived gender-based violence, were abducted by armed groups or had been recruited. Through body mapping and narrative interviews, we explored ways in which women visualise the impact of war on daily life in Central Africa. With our story-based methodology we hoped to engage with women’s experiences in a way that fostered respect and avoided re-traumatisation.

Body mapping offers a way to bring narratives of war to light. It describes a process of “creating life-size drawings that represent people’s identities within their social contexts” (Skop, 2016). As a biographical tool,body maps can be used to show and tell a person’s life story and reflect on important relationships or memories (Coetzee, Roomaney, Willis, & Kagee, 2019). In research, they allow participants to actively “participate” in the process of narrative creation and they prevent the preconceptions and assumptions from directing discussions. As such, they work well as a participatory qualitative research tool, so long as participants give their informed consent. The maps tell a story and simultaneously challenges those stories to be interpreted by participants and researchers through individual or group discussions.[i] This approach, anchored in narrative exploration, permits us richer understanding of human experiences and reminds us to see the world from other people’s point of view (Matthews, 2006). In this way, the project creates -through histories- a space for both scholarly and participative reflection on the collective and individual trauma brought on by war.

The discussions sparked by our body mapping exercises began the process for Miller and me to start understanding how these women have experienced and visualise war changing their everyday lives. In feminist research, the lived experiences of women have long been a focus of foundational research frameworks (Garko, 1999). Here, we hoped to enrich the still limited examination of women’s experiences in CAR through a focus on lived experiences and offering individual narratives as an essential source of knowledge for understanding war. We aimed to challenge more traditional and systemic conceptions of war, but we learned so much more.

Narratives of place, of time, and of home

Individual stories are connected to the body and the place around it. Johanna Selimovic’s work has long established individual stories as sources of new knowledge. She considers place, body, and story as “conceptual vehicles used to understand how agency in the ordinary is played out and how ethical subjects emerge in shifting spaces and times” (Selimovic, 2019).

Body mapping tends to bring to light findings that other research methods do not elicit. In the case of the women we talked to in CAR, it was the concept of home that came across most strongly: what home used to be, how it was experienced in the present, and how it could be rebuilt in future. Above all, we found war and home to be intertwined, in all sorts of shifting ways. For some women, war meant making a new life in a new place. For others, it meant reconciling what used to be with what was today and reconstructing ideas of home as a new space in the same place, as time passed and things changed.

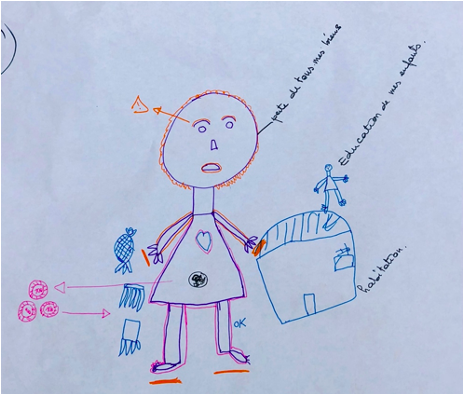

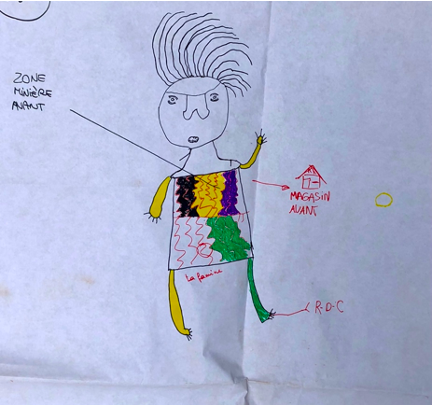

These ideas of spatial and temporal dislocation often underlie experiences of war, but are rarely brought to the surface in research. Another of the underlying themes that came through in our conversations around the body mapping was trauma, although it rarely was framed as such. When visualising and conceptualizing the traumas they had experienced, most women referred to loss and to the past. As the maps shared here suggest, the memories of what life used to be, where home used to be and how daily life was experienced since its loss remain salient and entwined with a sense of trauma. Above it is shown as the continual worry of providing for family and creating a home for them. Below, the map illustrates the shop one woman used to own as an aching reminder of the loss of, triggered every time she thought about her past life. Here, trauma is narrated through the memories of loss that their everyday lives now bring to the surface, loss of family, of safety, of rights such as education, and of belongings.

Experiences of Return and Healing at all Costs

There was a distinct focus coming through conversations and drawings that invited us – the researchers – to discuss how to move forward and what these women’s hopes were for the future. Dealing with the past seemed to be a means of grappling with the uncertainties that the future might hold.

On the one hand, war had often been experienced as displacement and, as such, a post-war future was understood or visualized by some women as a form of return, either to a prior time or space – or both. As this happened, the ‘blurry’ lines between war and peace and between safety and fear were constantly challenged. On the other hand, several participating women focused on the deep struggles they had gone through as refugees in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and how in some ways refugee camps were worse than war at home. These two diverging but complementary narratives underpin they ways in which fighting every day to move forward and support their families made sense.

For some it was about going back to what they had, and for some thinking through ways to move forward; but in every case, visualising war could not be separated from thinking in terms of time and space. It reminded us that there is no straight line between war and peace in Central Africa, that the two are intertwined in every place and at different times.

These narratives represent just a sample of the ways in which war is still visualised in daily life, from the memories of people who have been lost, the homes that have been destroyed, the journeys victims have been forced to take, and the struggles their have encountered to make a life again. The stories that we heard reminded us that it is only through paying closer attention to how war is understood by those who live through it that we will fully grasp its implications.

References

Coetzee, B., Roomaney, R., Willis, N., & Kagee, A. (2019). Body mapping in research.

Cronin-Furman, K., & Krystalli, R. (2021). The things they carry: Victims’ documentation of forced disappearance in Colombia and Sri Lanka. European Journal of International Relations, 27(1), 79-101.

Garko, M. G. (1999). Existential phenomenology and feminist research: The exploration and exposition of women’s lived experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23(1), 167-175.

Matthews, E. (2006). Merleau-Ponty: A guide for the perplexed. A&C Black.

Selimovic, J. M. (2019). Everyday agency and transformation: Place, body and story in the divided city. Cooperation and Conflict, 54(2), 131-148.

Skop, M. (2016). The art of body mapping: A methodological guide for social work researchers. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 28(4), 29-43.

[i] In CAR, we conducted group discussions after asking participants what they would prefer to take part in. In different contexts, body maps can be used as a public narrative illustration. In CAR, however, these were created as part of the research process and therefore remained anonymous and confidential.