'The Paul Nash of our era. No one has captured in art the destruction and suffering of modern warfare as powerfully. With his pen and brush he tells the stories of the suffering of the refugee and the migrant wherever the wars are in this turbulent world. There is terrible beauty in his drawings. He means what he paints, opens our eyes and hearts to the suffering, tells the tale of our fractured humanity, helps us to know more clearly the lives of others caught up in conflict, so that we can begin to mend shattered lives, to give shelter and homes and hope where there is so little.' Michael Morpurgo, writing about award-winning artist George Butler.

As part of a mini-series on the representation of war in visual media, we recently interviewed artist George Butler for the Visualising War podcast. George draws in pen, ink and watercolour. His art covers a huge range of topics; but he specialises in current affairs and his visual reportage from conflict zones like Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria has won plaudits from the likes of Jeremy Bowen. As George has said himself, his work often takes him to places which other people are trying to leave. In August 2012, for example, he walked from Turkey across the border into Syria where, as a guest of the Free Syrian Army, he set about drawing the impacts of the civil war on people and towns. Over the last decade he has been to refugee camps in Bekaa Valley (Lebanon), oil fields in Azerbaijan, to Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Mosul, and to Gaza with Oxfam, among many other places. His drawings have been published by the Times, the New York Times, the Guardian, BBC, CNN, Der Speigel, and a host of other media outlets; and they have also been exhibited at the Imperial War Museum North and the V&A museum, among other places. George has also recently published a book, Drawn Across Borders: True Stories of Migration, which tackles one of the many ripple effects of conflict and shines a spotlight on some of the humans behind the headlines.

In the podcast, we talked about drawing as a dynamic process: one in which the artist invests time – and during which, the people being drawn might come and go, shift position or mood, fade into the background or come into focus. George’s drawings capture the rhythm of a place over several hours, enabling him to convey a context and set of experiences that are less easily observed through the fast shutter speed of a camera lens. Another aspect of drawing that George relishes is how approachable and unthreatening an artist often seems. While a cameraman’s equipment might act as a barrier, a simple pad and pencil often gets people coming closer to look and ask questions, sparking conversations. Drawing on location involves listening to many different people and what they want to share; and what George hears then finds its way into the drawings as they develop.

George reflected on the combination of aesthetics and storytelling in his reportage. While he strives to make his art beautiful, he sees little point in an attractive image which is not telling an interesting story – one that uncovers less visible, ignored or forgotten aspects of a conflict. One thing that motivates his work is the desire to balance and round out our habits of visualising contemporary wars. We discussed the push and pull of media organisations and NGOs, who sometimes want an artist to focus on particular aspects of a conflict – and also the challenges that artists and photographers often face in deciding what is or is not appropriate to depict in any given context. Like another of our podcast guests, the photographer Peter van Agtmael, George clearly sees his drawings as fulfilling a documentary role, setting down a record for the future; but he is also interested in myth-busting, in particular when it comes to documenting different people’s experiences of different kinds of migration, as in his book Drawn Across Borders: True Stories of Migration. As reviews of this book have underlined, it is ‘a work of art, compassion and activism, with journalist and illustrator Butler using his craft to bear witness to and build awareness of the effects of war on civilians whose lives are treated as mere collateral for those in power.’

Featured below are some of the images which we discussed in the podcast, not just from Drawn Across Borders but from George’s wider portfolio of work.

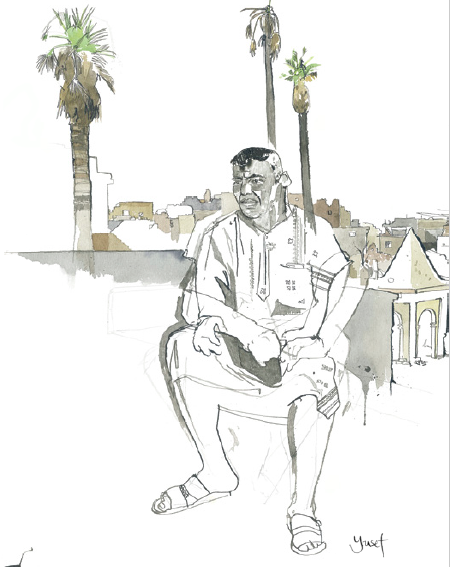

'I sat to draw Yusef Fateh, whose home had once sat at the bottom of the mosque minaret. Yusef told me, "In April 2015 I was accused by Daesh of smuggling people out of West Mosul, which I admitted. I was blindfolded and spent eighteen days in a Daesh prison. I was thrashed 300 times." He showed me a tattered copy of his Daesh court paper. "They released me at 11 am on a Friday. They threw me onto the street and said "If you look round we will kill you directly." At 12pm I packed and left for Syria without my family." Yusef returned in October 2017 to find his home destroyed by Daesh, along with the al-Nuri mosque. He told me he cannot find work because of the wounds on his back, but like many others sees this place as his home.' Drawn Across Borders, p. 47.

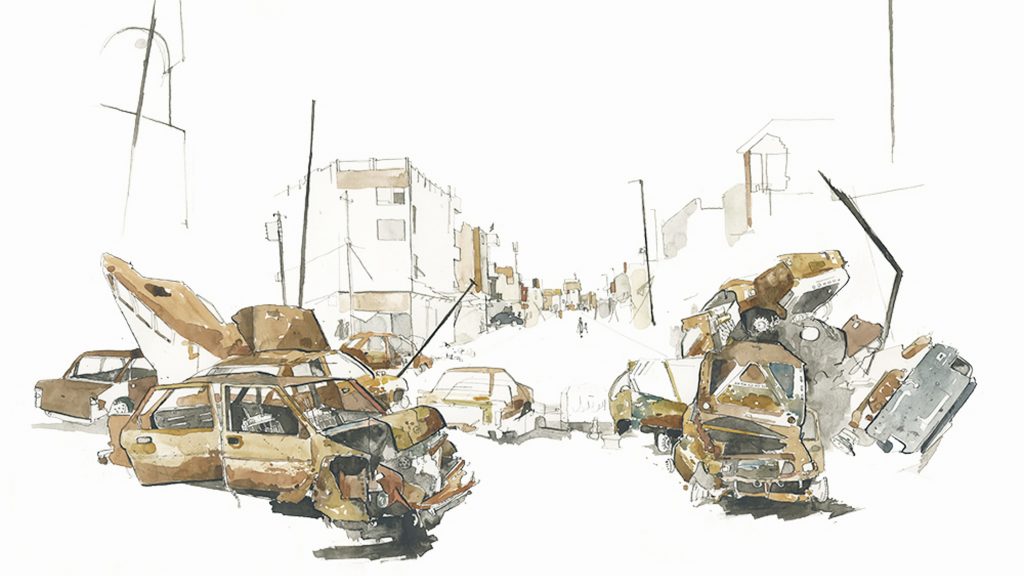

Mosul 2017

Credit: George Butler https://www.georgebutler.org/portfolio/mosul-liberation

Yusef Fateh, Mosul 2017

Credit: George Butler, Drawn Across Borders

'...in the town square I drew children playing on a burnt-out government tank as two old men examined the total destruction of their town in bewilderment. Their homes would continue to be the target of government air strikes for years to come.' Drawn Across Borders, p. 8.

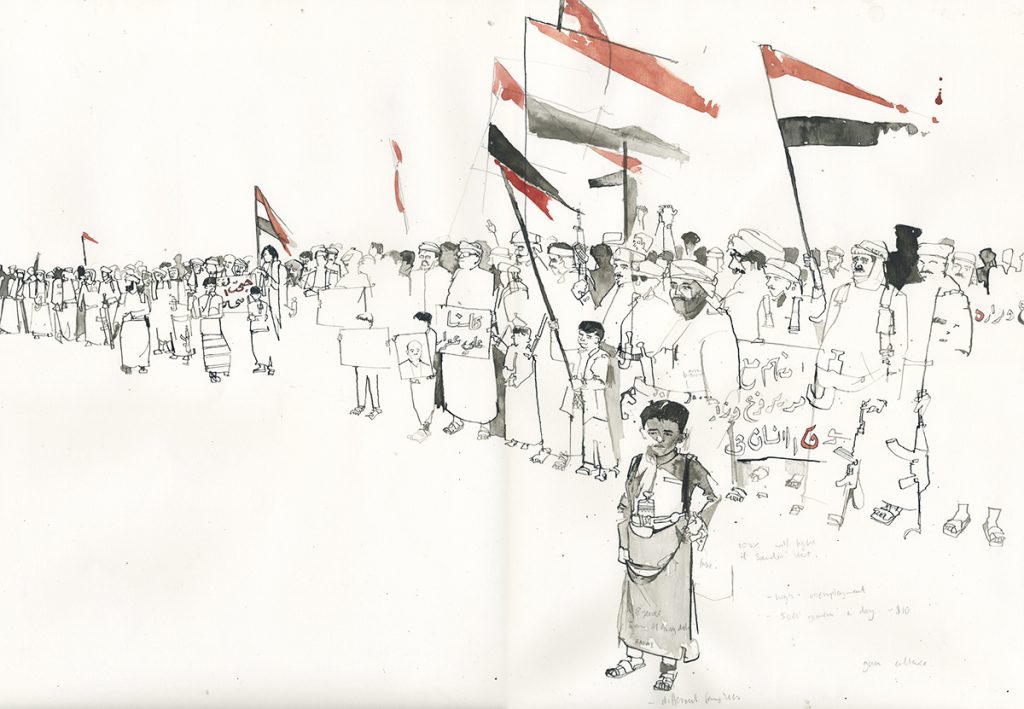

The image below (drawn in Azaz, Syria, 2012) perfectly captures George Butler’s style: a rhythmic drawing that keeps pace with the changing scene as people come and go; some features fleshed out in detail and colour; but also plenty of blank space that poses questions, reminds us of the incompleteness of any image, and gives our eye and mind time to wander and reflect.

Azaz, Syria, 2012

Credit: George Butler https://www.georgebutler.org/portfolio/syria

'I wandered through the town with Muhammed and saw the bakery. I had to draw quickly because of the pounding Syrian sun. People queued in the heat for up to three hours and, as Muhammed explained, each person was only allowed three flatbreads a day'. Drawn Across Borders, p. 10.

In the image below (Azaz, Syria, 2012), some individuals are depicted in detail, others as silouettes – bringing the individual and universal together in one picture. The red tractor is a reminder of the distance some have travelled to join the queue; the man in the foreground evokes the weariness of many.

'That evening a member of the Free Syrian Army called Firas took me to visit one of their prisons in Azaz. One man behind the bars looked at me intimidatingly. I assumed he was cross that I was drawing him. He held my gaze, unflinching, as I drew. Then after fifteen minutes or so he asked if he could move. All along he had been posing for the strange illustrator.' Drawn Across Borders, p. 11.

This image below got us talking on the podcast about the relationships which an artist can strike up with the people he/she is drawing, and how what you think you are seeing may be rather different in reality.

'Bassam's father sat at the foot of his bed, in black, occasionally putting a reassuring hand on his son's foot as he struggled through the painkillers. "Art cannot change anything," he said to me, and in this moment I believed him. My instinct was to leave without finishing the drawing. But another man in the corner said passionately "These are the sorts of scenes that the world should see. They are important to show the people what is going on here." Perhaps it was these contradicting opinions that led to the unfinished nature of this picture.' Drawn Across Borders, p. 36.

This image below (Syria, 2013) got us talking on the podcast about the power and limitations of art, and how artists like George manage the often very difficult decisions about what of war and other people’s sufferings to capture (or not) on the page.

‘Ahmed, 10, was rocketed on Feb. 13., and lost his leg. There doesn’t seem anything more mundane than drawing when you are standing next to a child that has lost his mother, his brother and his leg within the last 48 hours.’ George Butler, Drawn Across Borders

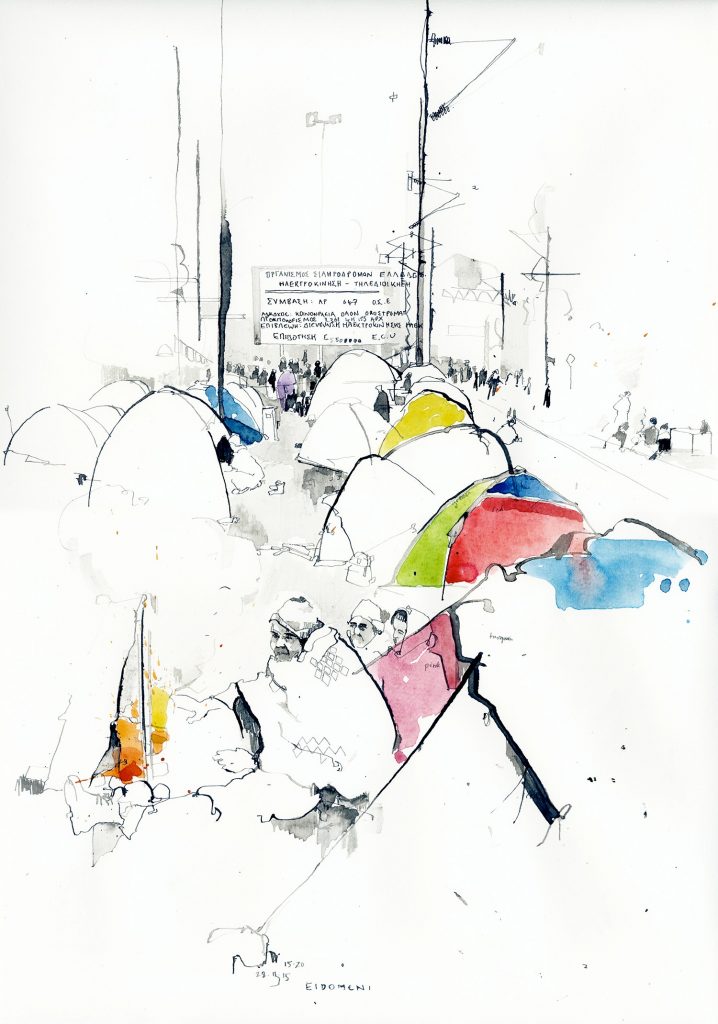

'...I spoke to fifteen-year-old Ahmed, who described his journey here: "Life in Iraq was fine until armed groups came. We left our homes - what else was there to do? We fled to the mountains. I stayed for eight days without food or water - nothing was there. Children died of hunger - nothing was there. We crossed into Turkey on foot. It took us one to two days' walking. Yes, we were scared. We walked at night - and it was scary on the boat too. It was difficult - the sea waves were a metre or two high. We had children on the dinghy... 150 people on the boat." Drawn Across Borders, pp. 20-21.

These drawings below reflect on the so-called ‘refugee crisis’, which became very visible in Europe in summer 2015. One of George’s aims is to address some of the pernicious myths that exist around refugees, to get us thinking differently about what they are queuing for, and to humanise their experiences.

Greece, 2015; George Butler,

Drawn Across Borders: True Stories of Migration

‘Queuing for Food’: George Butler,

Drawn Across Borders: True Stories of Migration

'These families showed us the belongings they had carried with them from their homes. They were the belongings of people who had not planned to leave Syria. They were the items they picked up in a rush, or as the lights went out, the items that were left in the rubble of their homes or that they had in their cars when they abandoned them at the border. These were people who thought they would be going home very soon.' Drawn Across Borders, p. 48.

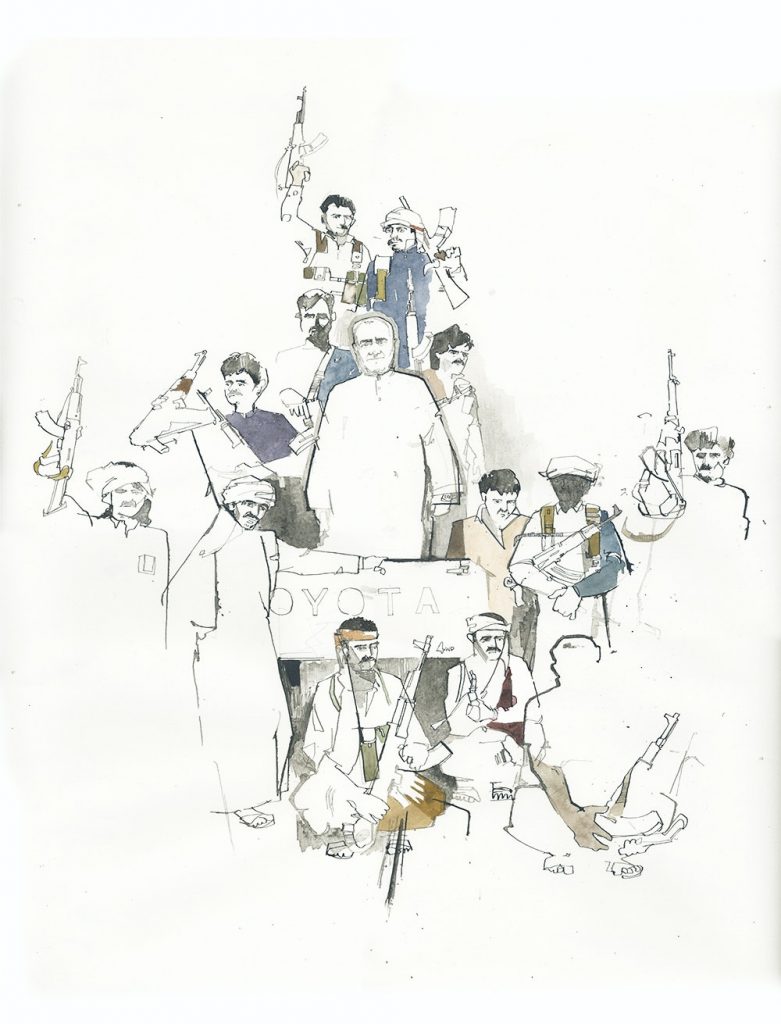

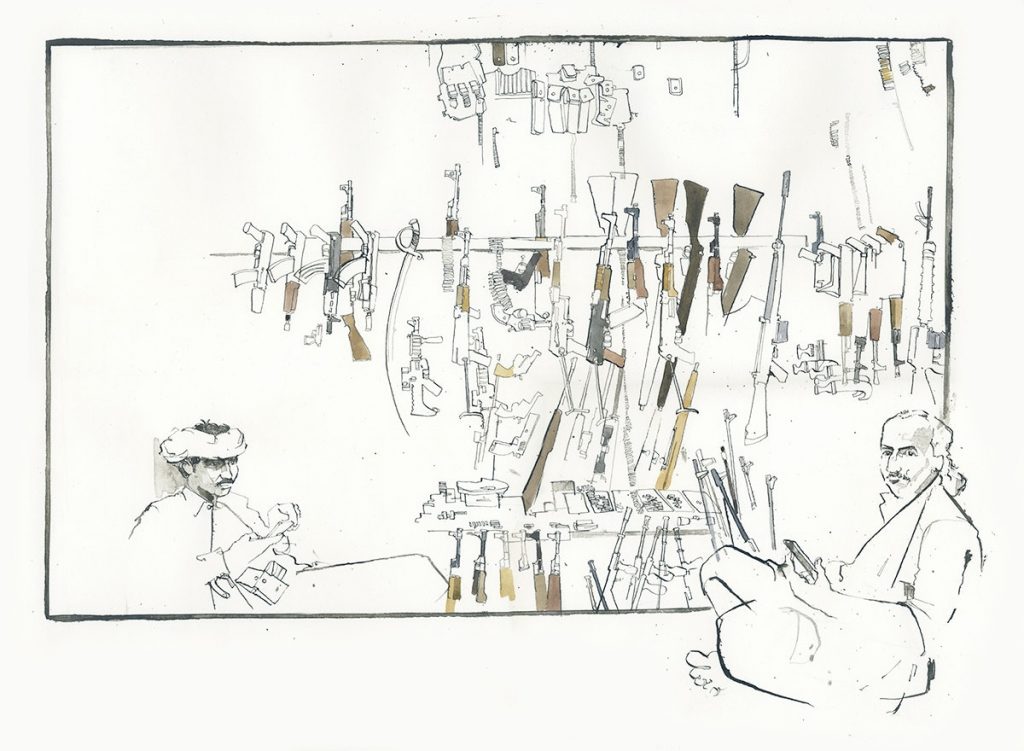

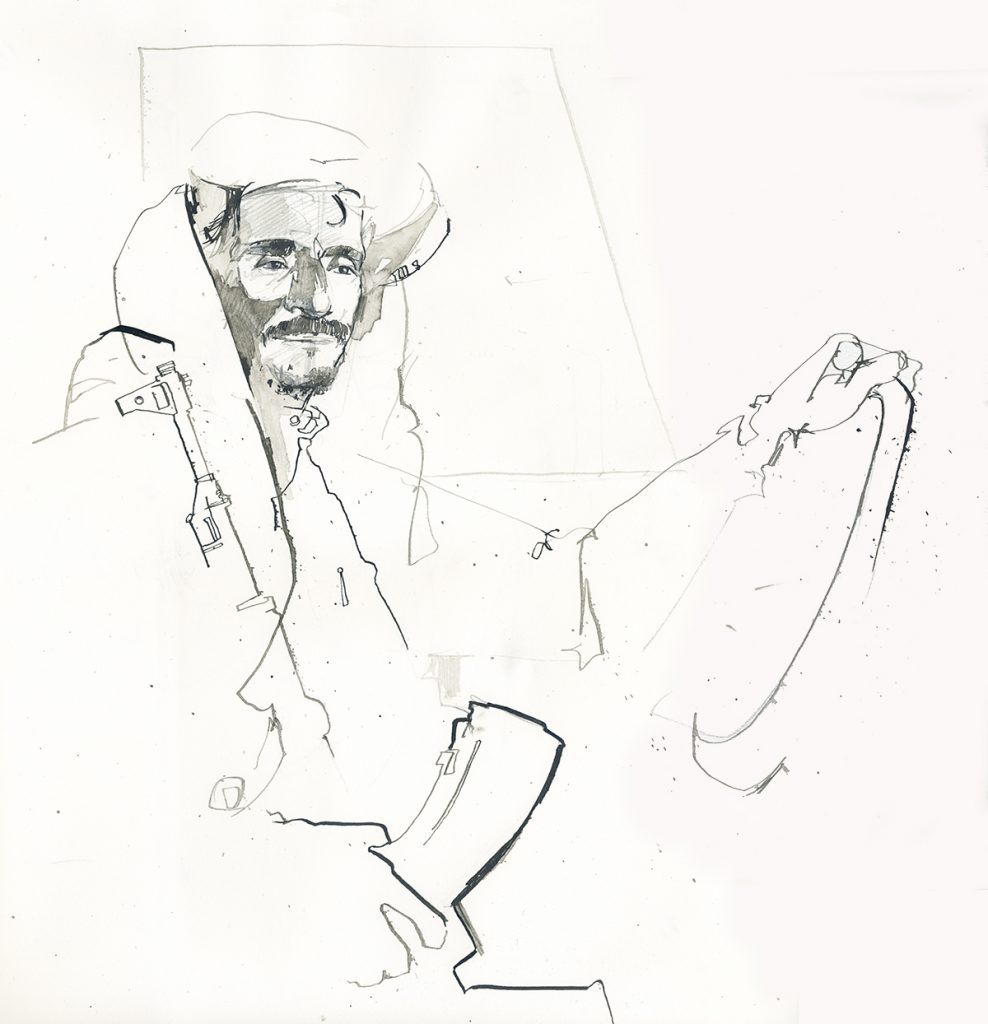

Yemen, one of the less visible conflicts in the world at present, but one of the most destructive:

Yemen. Credit: George Butler https://www.georgebutler.org/portfolio/yemen

You can listen to the podcast here. More images are available on George’s website and you can buy a copy of his book here. Following his experiences in Syria, George and a group of friends set up the Hands Up Foundation, which funds health and education programmes for victims of conflict.