As part of a mini-series of podcasts looking at artistic representations of and responses to conflict, we recently interviewed Roberta Bacic, a Chilean collector, curator and Human Rights advocate, about the ‘Conflict Textiles‘ collection which she helped to build and now oversees.

In 2008, Roberta was involved as guest curator at an exhibition called ‘The Art of Survival’, commissioned by the the Tower Museum and hosted in Derry-Londonderry. The exhibition was focused on different women’s experiences of survival, and it was inspired in part by a Peruvian arpillera (a form of tapestry) which Roberta had brought to a meeting, to illustrate how women on both sides of the long-running conflict in Peru during the 1980s and 1990s represented their experiences and used the stories they had sewn as testimony at the subsequent Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

From there, the idea of curating a physical and digital collection of Conflict Textiles grew – and today the collection comprises arpilleras, quilts and wall hangings from many different parts of the world, including Chile, Argentina, Northern Ireland, Croatia, Colombia, Germany, Catalonia, India, Zimbabwe and Syria. A digital version of the collection is based at Ulster University. These works of art not only depict conflict and its consequences. In many cases, they embody the resilience of the people who created them, and they can be read as acts of resistance too: fabric forms of storytelling that advocate for justice and promote alternatives to conflict.

In the podcast, we discussed what these Conflict Textiles can teach us about habits of representing and visualising the consequences of war; and we also reflected on how different art forms, including sewing and making, can help promote, envision and engender peace. Roberta explained the history of the arpillera tradition and its often communal dynamics, with women coming together in real life as well as on canvas to protest against armed violence and human rights abuses. The process of making is often as important as the finished product, helping those involved to build community, raise their (often marginalised) voices, process trauma and find some resolution or healing. Some Conflict Textiles have been crafted by first-hand victims of war; others have been crafted by others in solidarity, to remember, to stand alongside victims, and to encourage others to take a stand too.

Over the course of the podcast we talked about a number of specific textiles, including the one pictures above, ¿Dónde están los desaparecidos? (‘Where are the “disappeared”?). Created in the 1980s by Irma Müller, it depicts what many people experienced under Augusto Pinochet’s regime in Chile, after he seized power in a coup d’etat in 1973: the forced disappearance of their loved ones. It is made from pieces of colourful material sewn into a picture on a hessian (burlap) backing. A group of women in colourful dresses are protesting in front of the Courts of Justice. They hold a banner reading: ‘Where are the detained and disappeared?’ On the right-hand are silhouettes of two armed police, identified by their green clothes and their car, but the women ignore them and continue with their protest. The sun is in the sky (as often in arpilleras), but two large clouds sit in the centre, perhaps symbolic of the troubles below, and the women’s colourful clothing is set against the slate grey of the court buildings. There is menace as well as resilience in this picture, which embodies the power of victims and marginalised groups to raise their voice and demand justice.

This arpillera below is called La Cueca Sola (‘They Dance Alone’). La Cueca is a traditional Chilean Dance, normally danced in pairs with women wearing colourful skirts. In the textile, however, the women wear black, and instead of a flower in their shirt pockets there is the silhouette of a loved one who was ‘disappeared’ by Pinochet’s regime following the military coup in 1973. Groups of women took to performing La Cueca Sola in front of Pinochet’s headquarters as a form of protest, and this inspired a number of conflict textiles on the theme – as well as the song by Sting, ‘They Dance Alone’.

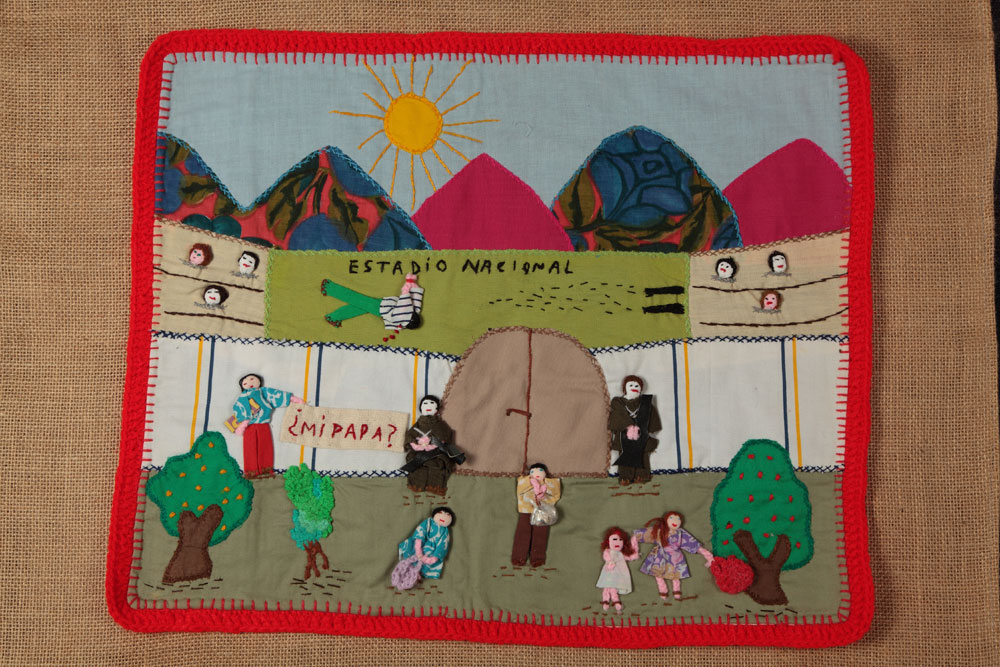

This arpillera is also from Chile, and it depicts one manifestation of the violent aftermath of the military coup in 1973: executions in the national stadium. It was made by Maria Mendoza some years after the events it depicts. A note tucked in the back explains: ‘The biggest of all concentrations that I think the dictatorship had was the National Stadium. There, many friends and companeros died. That’s why I don’t want pardon or forgetfulness.’

Violar es un crimen (‘Rape is a crime’) was made in 2008 by a woman who lived through the civil war in Peru from 1980-2000: “In October 1985 many people were killed in Ayacucho and women were raped, but nobody protested. Two groups of us decided to demonstrate in front of Comando Conjunto (Joint Military Command) in Lima since the people … living in Ayacucho felt too vulnerable to do so …. We displayed a banner … ‘Rape is a crime’. .. Five of us decided to make an arpillera of our action to show we do not condone such brutality.”

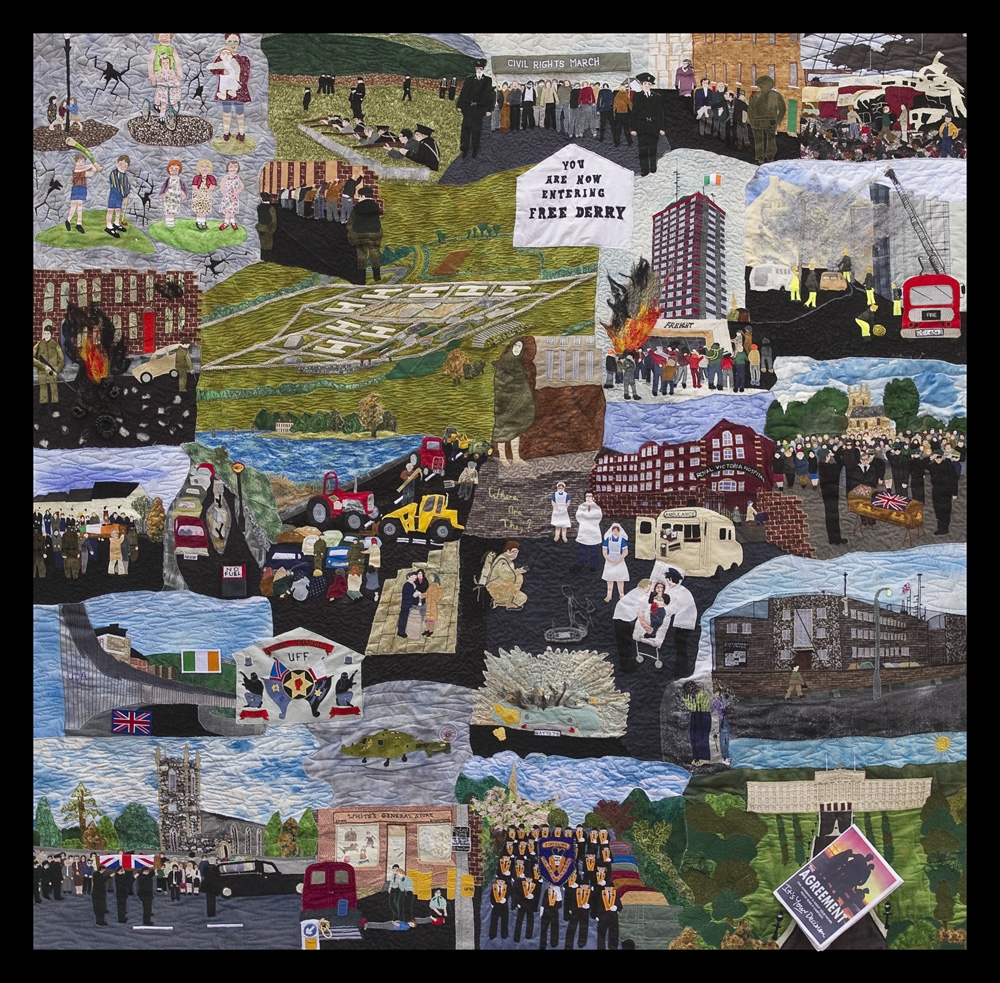

This Quilt of Remembrance is the work of a cross-community group of WAVE trauma centre participants. Spanning four decades it depicts life before The Troubles in 1969 and key events during The Troubles; it closes with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 which, suggestively, is hanging by a thread from the bottom of the piece. As Roberta explains on the podcast, it blends local quilting techniques with the aesthetics of the arpillera tradition, mixing the two textiles ‘languages’. Participants involved in making it talked of the role it played in their ‘journey of healing’.

‘The House we had to leave’ was stitched by a group of women refugees from Croatia in 1995. As the text on the Conflict Textiles website explains, Ariadna is a women’s project where, since July 1993, women from Rijeka in Croatia, together with refugee women from Bosnia, have created a centre of mutual help and self-help for women in need. Having abandoned home and hearth in utter haste, these women’s only asset in the alien land of their refuge is their skill to manufacture traditional handicrafts… the women decided to create a piece with a house of their own, made out of cloth so that grenades and bombs could not destroy it. As the house began to take shape, the work awakened memories of old customs, songs, and traditions… The women even designed a garden, their own private sanctuary. The piece provided each woman with a sense of home and belonging, though she was miles away in a strange new land.

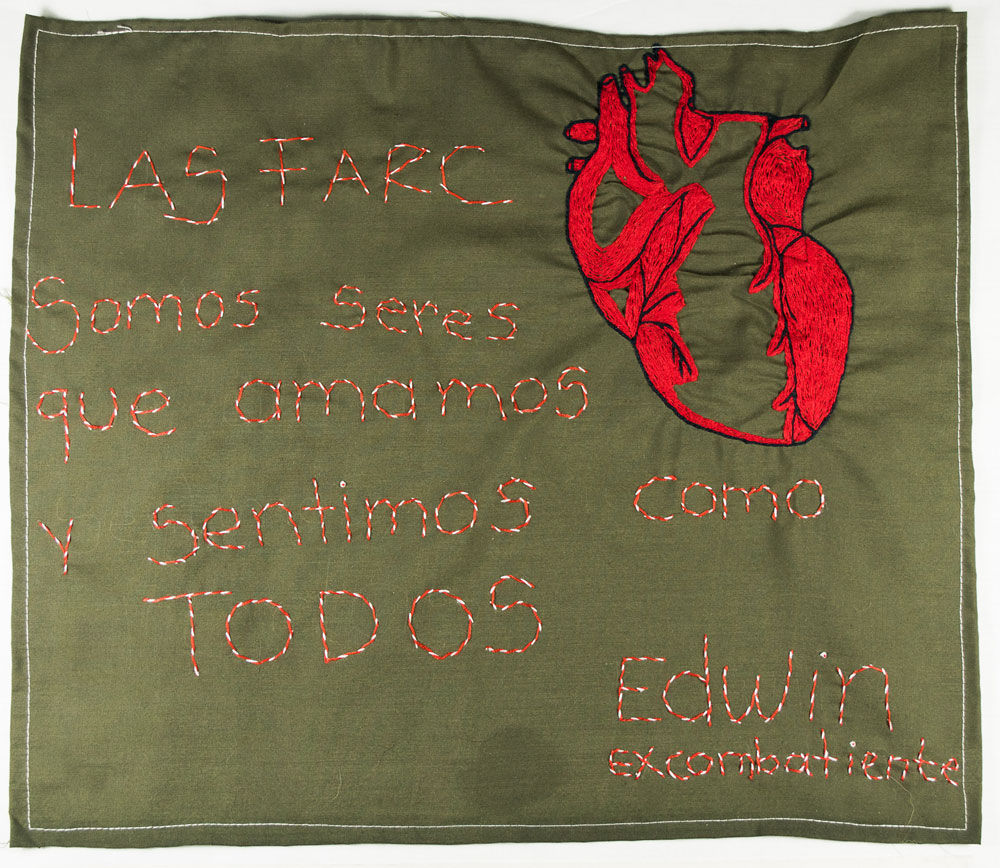

Un corazón como el de todos (‘A heart like everyone else’) was stitched in 2019 by a young ex-combatant of the demobilised guerrilla group FARC. He took part in a project called ‘(Un-)Stitching Gazes’ – an idea which resonates with what the Visualising War project is interested in, because it speaks to the idea that looking differently at things can help reconfigure the world around us. This project gave ex-combatants the chance to reflect on the transformation process they were undergoing, and he wrote about his work: ‘When I’m embroidering, I concentrate. There’s even a moment when I don’t think about anything. I focus on the stitches, that I do them well… And it’s like a good feeling. As in one way or another, with each stitch, it’s like letting go of those burdens that one carries, so to speak.’ He also commented: ‘I always hear that guerrillas are not human beings, that we are demons, they portray us as monsters. I chose a heart because it is a synonym for life, it is the most important organ.’ With this piece, ‘Edwin’ is processing his own experiences and also asking others to visualise him in new ways.

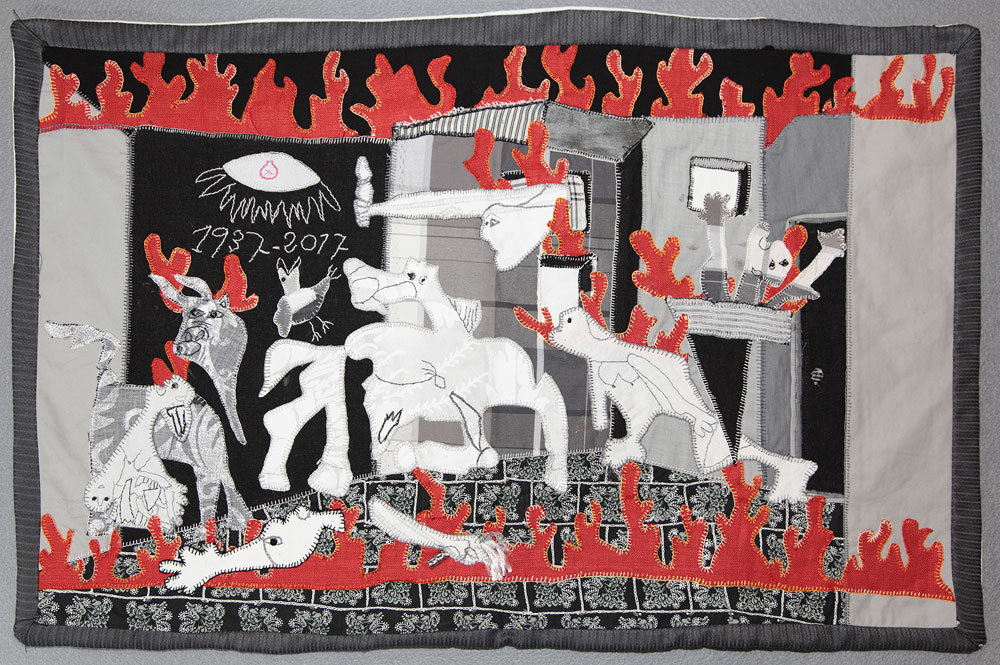

Mi Guernica (‘My Gernika’) was stitched in 2017 by a women whose family suffered when the German air force bombed Gernika in 1937. It uses an old family pillowcase (a family heirloom) as backing, and depicts a reworking of Picasso’s Guernica. It reminds us that prior representations of conflict always hover in the background of our own attempts to narrate it, but also that individual makers can personalise influential, canonical representations to tell their own story.

One very new arpillera in the Conflict Textiles collection is The word caused the outbreak of war – ‘Freedom’. It was made in 2020 by Sabah Obido, in response to an online exhibition she saw took part in during lockdown. Sabah is a refugee from Syria, and this arpillera was a chance for her to explore and process her experiences of conflict and displacement, and also to raise a really important question. The piece depicts scenes of peaceful demonstration which Sabah herself witnessed in 2011 and which ultimately triggered the long-running civil war in Syria. She uses a bright, cheerful image (the sun has a smile!) that shows women waving banners in English and Arabic, calling for freedom, to ask how those peaceful protests resulted in so much conflict and displacement. This arpillera captures the powerful work that Conflict Textiles can do, not only in giving makers an opportunity to process and articulate their own experiences but also in empowering them to ask difficult questions.

Some items in the collection have been made by protesters who are not direct victims of conflict, such as this banner by Thalia and Ian Campbell. “It’s No ******* Computer Game is our ‘drone for peace”, state Ian and Thalia. Made of light materials, it can be sent off and used worldwide.

We hope you enjoy the podcast, and urge you to browse the Conflict Textiles website further to find out more about the moving and powerful collection.

In 2019, colleagues at the University of St Andrews co-hosted a Conflict Textiles Exhibition called Threads, War and Conflict, inspired by some previous ‘Stitched Voices‘ exhibitions. You can find out more – and about the Visualising War project’s involvement – here. Some new creative work and publications are emerging out of this collaboration, so watch this space!