"Nearly twenty years after September 11, America’s recent wars are all but forgotten, though their consequences continue to reverberate. For the past fifteen of those years, I’ve documented the dissonance between the United States “at war” and the wars as they really are." Peter Van Agtmael, Disco Night Sept. 11.

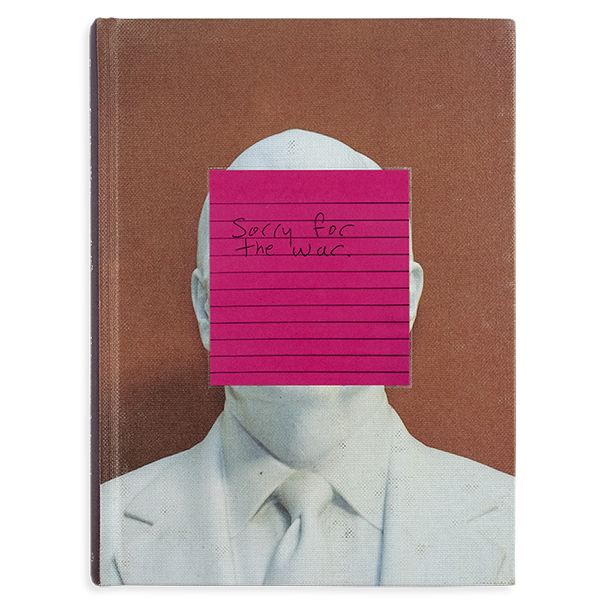

The Visualising War podcast recently interviewed award-winning photographer Peter van Agtmael. Over a career spanning 20 years, Peter has focused on representing different manifestations of the US at war. His first book, ‘Disco Night Sept. 11’, brought together images of America at war in the post-9/11 era, from 2006-2013.[i] His second, ‘Buzzing at the Sill’, focused on the US in the shadow of recent wars; it does not capture images of armed conflict, but examines aspects of American society that have been shaped by and helped to shape the wars that America has fought. His third book, ‘Sorry for the War’ explores the vast dissonance between how the US has visualised itself at war and how people on the ground (soldiers and civilians) have experienced those wars, particularly in Iraq and Afghanistan.[ii] Peter has won multiple prizes for these books, as well as being highly sought after by media organisations such as the New York Times and the New Yorker. For the last ten years he has also been working on capturing images of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine.

In the podcast, Peter talks about what motivated him to go to war as a photographer in the first place, and how his understanding of war and his approach to conflict photography have evolved over time. Aware that a single photograph can only capture one person’s perspective and a tiny slice of time, Peter underlines the importance of a multiplicity of images which together can build a sense of context, change over time and diversity of experience. He tries to document wars as holistically as possible, while still going deep and getting personal. He is particularly interested in unpicking the gap between our habits of imagining, viewing and understanding conflict and how it impacts people for real. There is a strong sense in his books that he is myth-busting, as he invites us to look critically at our own habits of visualising war and really stretches our understanding of war’s dynamics, impacts and aftermath. You can hear his reflections in more detail in the podcast itself. This blog shares some of the images that Peter talks about from ‘Disco Nights Sept. 11’ and ‘Sorry for the War’, along with some of the text that accompanies them in his books.

The following images are from ‘Disco Night Sept. 11’, about which Peter writes:

"Despite all the death and confusion and isolation and impotence these pictures represent, I know they can only be a slender document. There are so many simultaneous existences and we can only be present in one. For every story that is recorded there are nearly infinite ones we’ll never know. The real weight of destruction is still happening constantly in anonymity across Iraq and Afghanistan and America, in endless repetition of all that has come before. If I found any truth in war, I found that in the end everyone has their own truth."

FORT IRWIN, CALIFORNIA. USA. 2011

“A mock courtroom for soldiers deploying to Iraq. This training exercise simulated an Iraqi criminal trial. An American Army lawyer set forth evidence to prosecute an “insurgent” for ties to resistance groups. After hearing arguments from both sides and reviewing evidence, the Iraqi “judge” dismissed the case. During the war, American lawyers were rarely obliged to engage with the Iraqi criminal justice system. Many detainees were held for long stretches without trials. No American soldiers were prosecuted by Iraqi courts. In October 2011, President Obama announced that all U.S. troops would withdraw from Iraq by the end of the year. Although the American and Iraqi governments hoped to keep five thousand American soldiers to assist in training the fledgling Iraqi security forces, negotiations broke down after the Pentagon insisted that American soldiers retain full immunity under Iraqi law. The Iraqi government refused, the deal collapsed, and the last American soldiers left Iraq in December 2011.”

As we discuss on the podcast, this image captures the gap between how the US visualised their likely activities in Iraq prior to engagement and how differently events turned out. An empty set where men rehearsed for a performance they never ended up delivering.

“A Marine with a village elder from Mian Poshteh, a rural village in southern Helmand Province. The Marines were trying to build the Afghan Army. There were 240 Americans in the outpost, but only a few dozen Afghan soldiers. The local language was Pashto, but only a few of the Afghan soldiers spoke it; they were from other parts of the country. Relations with the local elders were tense. The Afghan soldiers were often accused of stealing when doing house searches in the village. Although Mian Poshteh was only one kilometer from the base, the Marines and Afghan Army were often attacked nearby. The Marines asked the elders if they would vote in the upcoming elections. “The Taliban will chop off our fingers,” was the reply (the index finger is stained purple after voting to make sure there are no repeats). The Marines asked why they wouldn’t reveal the location of the Taliban. The elders replied, “You go back to your base at night, while the Taliban are all around us. If we cooperate, they will kill us.” They went on to say that there was no fighting before the Marines came, and that they should just go away.”

This image perfectly captures the weariness both sides experienced at trying to keep some kind of dialogue going and build temporary bridges against all the odds.

“A U.S. Blackhawk helicopter lands at the Ranch House, a small American outpost deep in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan. There were no decent roads and all medevacs, re-supply and transport were done by helicopter.

Blackhawks were in short supply, forcing the U.S. military to turn to outside contractors. They rented ex-Soviet helicopters, rickety and ancient and known as “Jingle Air.” They came with pilots, some of whom had served in the Russian Army during the previous war in Afghanistan. They were storied figures, legendary for their bravery under fire and rumored to be heavy vodka drinkers in flight.”

As Peter explains on the podcast, this image captures some of the things we romanticise about war: life on the edge, moments of adventure, the seductive ‘beauty’ of an iconic war image.

“A child wounded in the abdomen by shrapnel from a car bomb. After surgery, several of the smitten medics posed for pictures with the semi-conscious girl.”

As we discuss on the podcast, without Peter’s text this image might strike the viewer simply as a tender moment between soldier and injured child; with the text, a much more complex and disturbing story emerges. The girl becomes a double victim, injured and then mauled about for the camera by soldiers who care deeply but also exploit her in their efforts to get in touch with their own feelings.

In ‘Sorry for the War’, Peter’s collection of images is even more diverse, capturing everything from a burnt-out classroom in Mosul, to a shrapnel injury that has begun to heal, to the in-between existence of children in a city that hangs somewhere between war and peace.

“The first Easter in Qaraqosh, Iraq, after it was liberated from ISIS. A few miles away, fighting continued in Mosul. Though the area around Qaraqosh was relatively quiet, the town lay in ruins. ISIS graffiti was scrawled on the walls of the church, ranging from the mundane (“Ahmad was here,” “Take off your shoes”) to the sinister (the ratio of ingredients for making car bombs). Shattered Christian religious artifacts used by ISIS for target practice had been swept into a corner, and a decapitated full-size statue of Santa Claus was sprawled in the courtyard. Most of those attending the church service were Iraqi soldiers and journalists, but a handful of local residents came, too, including a small girl in bright-colored robes who was a particular darling of the Iraqi soldiers. They cooed at her outfit and swept herup in their arms to cover her in kisses.”

Baqofa. Iraq. 2015.

Mosul. Iraq. 2017.

Tovarnik. Croatia. 2015.

North Ogden, Utah. USA. 2019.

At the end of ‘Sorry for the War’, Peter writes:

"There’s a feeling of fulfilment but also of emptiness when the complexity of my experiences inadequately collapses into the two dimensions of a photograph. When I began this work, my confused and naive desires mingled uncomfortably with a sense of duty to journalism and history. Somehow, the unexpected grace of these experiences has left me lighter, despite the horrors. Yet I am left with the understanding that the work is far from over."

You can find out more about Peter’s work on his website and instagram page. His reflections on the podcast shed fascinating light on the challenges and opportunities of conflict photography to challenge how we all visualise war.

Alice König, 29.11.21

[i] Readers can find two excellent reviews here: https://www.1854.photography/2014/05/peter-van-agtmaels-disco-night-sept-11/ and here: https://aperture.org/editorial/peter-van-agtmael-disco-night-sept-11/.

[ii] Reviews here https://www.magnumphotos.com/newsroom/sorry-for-the-war-peter-van-agtmael/ and here https://time.com/5948899/peter-van-agtmael-sorry-for-the-war/.