The Visualising War podcast recently interviewed Roman historian Dr Jon Coulston about representations of war on Trajan’s column, a huge victory monument erected in Rome in 113 AD to commemorate the emperor Trajan’s victory over the Dacians.[I]

As Jon explains in the podcast, Trajan reigned from 98-117 AD. In 101-2 and 105-6, he came into conflict with King Decebalus, whose kingdom – Dacia – bordered with the Roman empire across the river Danube. The column narrates the story of both Dacian campaigns, commemorating Decebalus’ defeat and Trajan’s victory through a sculptural frieze that winds all the way from bottom to top. The column was probably commissioned by the Senate of Rome, but it must have been influenced by the account the emperor himself wrote about his Dacian campaigns; and the designers and sculptors would have been keen both to please him and to meet wider societal expectations in their depiction of his military achievements. As Jon puts it in the chapter he has recently written for our Visualising War in Antiquity volume, Trajan’s column does not simply tell the tale of the Dacian Wars; it provides an index of how Roman victory and ‘barbarian’ defeat were defined, idealised and projected in Roman society.

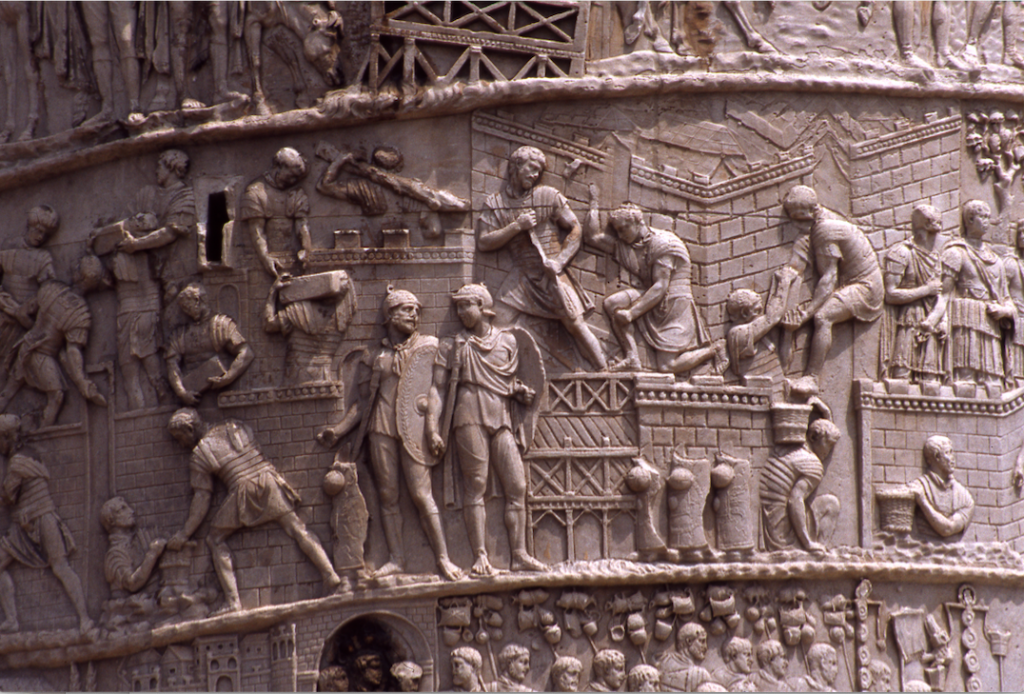

In the podcast, Jon talks about the mix of historical realism and idealistic storytelling visible on the column. The sculptors were clearly briefed to depict contemporary Roman soldiers and Dacians, wearing clothing and carrying weapons that a Roman viewer would have recognised; and some of the scenes carved on the column narrate episodes in the campaigns or specific events that really happened. Some of the representation is more generic, however: there are stock scenes of fighting, fort building, motivational speeches and enemy submission that reflect shared ideals and long-established habits of visualising war more than reality. Some of the column’s depictions of battle are reminiscent of Classical Greek sculptural reliefs showing mythical battles between gods or giants, while other set-piece scenes were designed to evoke Roman military ideals such as discipline, organisation and technological skill.

Building camps and forts (Jon Coulston)

Trajan’s army advances to battle (Jon Coulston)

The column’s depictions of the Dacians supports its idealising of Roman military success. As Jon points out, there is a strong Roman momentum travelling all the way up the column, with Roman forces advancing inexorably towards the top as Dacians retreat. While Dacians are seen fighting back strongly in places, ‘their war-making abilities are basic… and their organisation is chaotic.’ Dacian mountains, forests and rivers are tamed by Roman forts and bridges, and the Dacians themselves are systematically overpowered. They die in great numbers, and those who survive are represented bound or humiliated. Decebalus’ leadership is contrasted, of course, with Trajan’s. The emperor is not depicted fighting himself but he makes regular appearances on the column as a commanding presence, with stock scenes underlining his virtues as a general.

Trajan addresses the army (Jon Coulston)

The death of Decebalus (Jon Coulston)

In Jon’s words, the reliefs of Trajan’s Column were intended to assert Trajan’s achievements in war both through their attention to Roman and barbarian military realities and also by framing actions in intrinsically Roman terms, conforming to the expectations and interests of the Roman audience. The intricacy and volume of scenes on this huge monument are a staggering sculptural achievement, marking a high point never again equalled for contemporary detail and reportage in the Roman world. At the same time, the column presents Roman military activity in highly idealised forms, reflecting contemporary societal attitudes towards battle, generalship and military victory.

Jon reflects that the impact on the viewing public of the monument’s scale, lavishness and message must have been profound. The column formed a nodal point of public communication and imperial patronage at the geographical centre of Trajan’s Rome. Towards the end of the podcast, he also talks about the column’s influence on later triumphal monuments and wider habits of visualising war. Although its representations of war are very specific to the Roman context, it has ‘cast a tremendous shadow across military history ever since’. From the 2nd century AD through to Louis XIV and the American Civil War, it has not only shaped subsequent habits of representing victory; it has influenced the ways in which later military generals imagined themselves and even informed the ways in which some wars and battles were conducted.

Scenes on the column may have been coloured

https://www.relivehistoryin3d.com/2019/11/10/trajans-column-full-color-reconstruction/

As Jon explains in his chapter for our volume, ‘the sculpted reliefs of Trajan’s Column in Rome have been mined as a prime pictorial source for historical events, imperial display, concepts of war, victory and peace, Roman military ethos, architecture, tactics, ethnography, military organization, transport, and both Roman and barbarian dress and equipment.’ Crucially, it has much to teach us not only about the realia of Roman warfare but also about Roman habits of visualizing war and conquest. It stands as a valuable reminder that the relationship between narrative and reality is complex: narratives of war reflect reality up to a point, but they are influenced by a host of other factors, and their creative, evocative, idealistic representations of past campaigns have a habit of shaping later approaches, mindsets and behaviours in the real world.

If you want to find out more about Trajan’s column, you can listen to the podcast here. A version with captions and images will also be available on our youtube channel. More images and information can be found on Jon’s project website. We hope that this podcast episode inspires you to delve into other Roman representations of war[ii] and to keep thinking about their influence on modern habits of imagining and understanding military conflict.

Alice König 6.5.21

[i] This article offers an excellent introduction to Trajan’s column and how we might read the war story carved on it: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/trajan-column/article.html.

[ii] Dillon & Welch, Representations of War in Ancient Rome is a good starting point: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2006/2006.08.55/.