Troy: Fall of a City. Photograph: Graham Bartholomew/BBC/Wild Mercury Productions

I watch very few television programmes about ancient Greek and Roman history, literature and culture: when your day job is teaching and researching classics, these shows can be a bit of a ‘busman’s holiday’: I either know the material already, or (more often) I’ve become so specialized and limited in my expertise that huge swathes of ancient culture and history have become ‘news just in’. It’s not great to feel that you ought start taking notes at 9pm on a Friday night! Then there’s one’s insecurities to manage. If my week’s teaching has been a bit flat or difficult (Homeric dialect, anyone?), the last thing I want to see is Beard, Hughes, Hall, Cartledge or Scott doing a great job of making the ancient world irresistibly fascinating and accessible. Finally, there’s the ‘i’ word: we academics are now required by the government to make our research and expertise ‘impactful’ upon wider society and culture, and each department is regularly evaluated on how well it is going about this. That makes it even less relaxing to watch other people popularizing your subject to massive audiences with skill and verve.

But with film and television drama, it’s a different matter. Troy (Wolfgang Petersen’s quasi-Iliad for the big screen); Atlantis (BBC1’s now-defunct Greek mythology mash-up); Plebs (ITV 2’s Up Pompeii! for post-Millennials): I have sought them out and enjoyed them all. And I have not been very worried about real or alleged liberties taken in terms of historical ‘accuracy’ or ‘faithfulness to the original’. After all, most ancient myths exist in several different versions. In the case of Greek epic and drama, ancient authors themselves often changed existing elements of a story or made new stuff up in their re-tellings. Whoever Homer was – or ‘whatever’ if you think the Iliad and Odyssey were almost entirely shaped by centuries of oral song tradition rather than one master poet – it’s clear that both epics contain elements which were invented or adapted to suit these particular versions of two specific slices of a much longer story. So, I rather like the idea that film and television are enriching and adding to an existing store of many different ‘takes’ and emphases.

Of course, some changes from familiar ancient material can seem a step too far. When Petersen didn’t have any gods appearing in Troy – Julie Christie’s Thetis was an exception – a lot of film critics and classicists got very unhappy. (The film is hated by many people I know, and it does have flaws, but I’m rather fond of it as a creditable attempt to make sense of Homeric-heroic ‘values’ such as kleos (fame and reputation after death) and timē (honour, status) for a mainstream audience.)

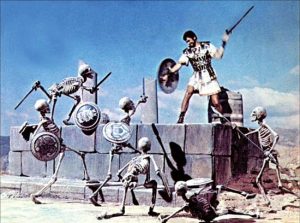

JTodd Armstrong in Jason and the Argonauts (1963), directed by Don Chaffey. © Columbia Pictures Corporation

But what exactly are we unhappy about when film and TV make such changes? Petersen’s Greeks and Trojans still worship the gods and worry about what they are up to, just as in Homer. And the Iliad’s many divine quarrels and political manoeuverings on Olympus wouldn’t have been best served by the sort of ‘dry ice and wafty white robes’ nonsense which we find in Clash of the Titans (1981). In any case, ‘departures’ from ‘the original’ don’t always make the story less engaging or worthwhile. The most iconic scene of the Jason and the Argonauts (1963) comes when Jason and his men find themselves fighting an army of stop-motion skeletons. In Apollonius’ epic The Argonautica these ‘sown men’ aren’t skeletons and Jason makes them fight amongst themselves until they destroy each other. If director Don Chaffey and effects animator Ray Harryhausen had stuck more closely to what’s in the ancient sources, that film would be much the poorer for it.

Perhaps we are worried that children and adults who are unfamiliar with Greek myths as preserved in Greco-Roman literature will end up with a false impression of what is (and what isn’t) in Homer, Pindar, Greek tragedy and the rest. Even worse, we think that they will say ‘I’ve seen Troy so I don’t need to know about the Iliad’. Well, that’s a risk with any decision to bring great stories and literature to the screen. But just as HBO’s Game of Thrones seems to have led more people to read the books on which it is based, and Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings created even bigger sales for Tolkein’s novels, some half-good telly or cinema ‘based on Homer’ has a good chance of sending its fans towards the actual epics themselves. The Iliad and Odyssey are well worth reading in a good translation, not least because they are highly vivid, dramatic and cinematic – and yet they ‘visualize’ thought, feeling, atmosphere and action in ways which neither big nor small screen finds it easy to capture with the same intensity.

BBC 1’s latest Saturday-night drama is called Troy: Fall of a City. It opening captions tell us that it is ‘based on Homer and the Greek myths’. The first episode went out last weekend and reactions have been mixed, to say the least. It’s neither easy nor fair to judge something after just one episode. But I thought it was very enjoyable – best watched with a glass of wine or two, perhaps. In my next post, I’ll offer some some first thoughts and observations on it from a classicist’s perspective. There will be **SPOILERS**.

If you are interested in classical story-telling and you are in or near St Andrews on Saturday 3rd March come to see TV and Radio’s Bettany Hughes give a free public lecture on the subject. Details of the time and venue of her talk and the ‘Advocating Classical Education’ project are here

Excellent statement of why we should just sit back and enjoy the drama, without making a drama of this and that! Best Tim Bowler

Thanks for this Tim and for your support on Twitter. Haven’t even had time to watch episodes 2-3 of T:FoaC yet. But hope to post more on it soon.

I completely take your point in changes and adaptations but what set my teeth on edge although it is maybe a small point was Helen referring to the myth of Actaeon and Diana.

Was it a deliberate talking point, not sure there can be another explanation

Dear Colin, thanks for your comment and sorry to take so long to reply: you have probably heard that we are in the midst of a major industrial dispute and I have myself been on strike. I did not really mind the use of ‘Diana’ as opposed to the Greek name ‘Artemis’. I saw it as a deliberate attempt to use a name which would likely be more familiar to a wider audience: ‘Diana goddess of hunting’ *feels* more a part of popular consciousness than Artemis. Shakespeare mixed together Roman and Greek names for gods in his poetry and plays, although I would have to check further to see whether he does so in any one play or sonnet. Hope to do another post soon when I’ve found time to watch beyond episode 1 on iplayer!

“After all, most ancient myths exist in several different versions. In the case of Greek epic … ancient authors themselves often changed existing elements of a story or made new stuff up in their re-tellings.”

Well said, and thank you for your wonderful writing. I share your view on Troy: Fall of a City, and even on 2004’s Troy. The Trojan War Epic is remarkable malleable clay for storytellers, ancient and modern. My “day job” is live performance storytelling stories from the Trojan War Epic cycle. Needless to say, the realities of live performance requires that I “repackage” the Trojan War epic into an approximate 2-hour story arc. But my audience still wants a “story”: with beginning, middle and end; and with heroes, villains, and of course, with a wooden horse. So do I stay “true to Iliad”? A purist would scream “NO”; but a Bronze Age storyteller (like Demodocus of The Odyssey) would, I think, offer more pragmatic advice: “Your audience has 2 hours, they want to be entertained, you need to eat, and they have GOLD. So give them a ripping good evening’s entertainment. After the show, they can “fact check” to their heart’s desire on Wikipedia.”

When I eventually became frustrated with all the “bits” of the plot I was having to leave out of my live show, I created Trojan War: The Podcast. That afforded me unlimited storytelling time, and I managed to get the FULL story arc down to about 25 hours! But even at 25 hours, I had to leave a host of conflicting accounts of plot and character on the cutting room floor.

Finally, I am bringing my live 2-hr show “HELEN, SOME HEROES, AND A HORSE” to the UK, from Canada, arriving in Oxford March 4. Will be performing at the Cheney School and at Radley School, and also delivering talks on “Being a 21st C Homeric Bard” at Oxford U. I still have some available days/evenings for shows/talks. Contact me if curious.

Dear Jeff

Thanks for your kind words and valuable observations, and sorry to take so long to reply: you have probably heard that we are in the midst of a major industrial dispute and I have myself been on strike. I hope your tour of the UK is going well. When I get a chance I will check out your podcast. Sounds amazing. Haven’t even had time to watch episodes 2-3 of T:FoaC yet. But hope to post more on it soon.