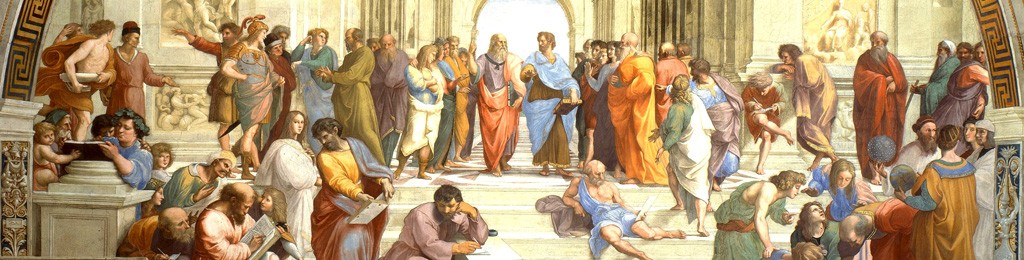

A couple of weeks ago my colleague Kleanthis Mantzouranis and myself hosted a conference called ‘Leaders and Leadership from Homer to Polybius’. Yale’s Emily Greenwood spoke on submerged and paradoxical female leadership via Socratic texts’ depiction of Aspasia (the rhetorician-courtesan allegedly ‘behind’ Pericles the politician) and Ischomachus’ model of shared household management in Xenophon’s Oeconomicus. Leeds’ Jamie Dow discussed how Aristotle’s Rhetoric presents more vs. less reputable models of argumentation against which the rhetoric of leaders (ancient and modern) can be tested. Then we had Roger Brock (also Leeds) on how Xenophon’s writing offers a much richer and more complex discourse on good and bad political and military ‘man-management’ than leadership gurus and management scholars have realized. Kleanthis’ paper showed how the use of violence as a tool of authoritarian leadership frequently backfires in Herodotus and he related this material to the historian’s wider concerns (moral, ethnographic, religious and sensationalist). Oxford’s Carol Atack used the rhetorician and Isocrates’ to focus on complex fourth-century BC debates about what the virtues of good leadership might be, not to mention how far, and in what way, they can be taught, imitated and transmitted. I had a stab at viewing the flawed leadership of the Homeric Agamemnon and Achilles through the lens of normative and empirical-descriptive work in ‘Leadership Studies’. Another of my St Andrews colleagues, Nicolas Wiater, then zoomed us forward several hundred years with a look at Polybius, a Greek historian who chronicled the rise of the Roman Republic. Nicolas discussed the ways in which Polybius’ depictions and assessments of Carthaginian and Roman leaders must be read against the backdrop of earlier Roman writing and the ideologically-loaded manner in which Roman generals memorialized and projected their success.

A couple of weeks ago my colleague Kleanthis Mantzouranis and myself hosted a conference called ‘Leaders and Leadership from Homer to Polybius’. Yale’s Emily Greenwood spoke on submerged and paradoxical female leadership via Socratic texts’ depiction of Aspasia (the rhetorician-courtesan allegedly ‘behind’ Pericles the politician) and Ischomachus’ model of shared household management in Xenophon’s Oeconomicus. Leeds’ Jamie Dow discussed how Aristotle’s Rhetoric presents more vs. less reputable models of argumentation against which the rhetoric of leaders (ancient and modern) can be tested. Then we had Roger Brock (also Leeds) on how Xenophon’s writing offers a much richer and more complex discourse on good and bad political and military ‘man-management’ than leadership gurus and management scholars have realized. Kleanthis’ paper showed how the use of violence as a tool of authoritarian leadership frequently backfires in Herodotus and he related this material to the historian’s wider concerns (moral, ethnographic, religious and sensationalist). Oxford’s Carol Atack used the rhetorician and Isocrates’ to focus on complex fourth-century BC debates about what the virtues of good leadership might be, not to mention how far, and in what way, they can be taught, imitated and transmitted. I had a stab at viewing the flawed leadership of the Homeric Agamemnon and Achilles through the lens of normative and empirical-descriptive work in ‘Leadership Studies’. Another of my St Andrews colleagues, Nicolas Wiater, then zoomed us forward several hundred years with a look at Polybius, a Greek historian who chronicled the rise of the Roman Republic. Nicolas discussed the ways in which Polybius’ depictions and assessments of Carthaginian and Roman leaders must be read against the backdrop of earlier Roman writing and the ideologically-loaded manner in which Roman generals memorialized and projected their success.

Finally, the sociologist Philip Roscoe,a colleague from the School of Management, made us step back from the ancient world in order to think about the agendas and interests which might constitute ‘leadership’ as an object of study and going concern in the first place. He gave us an entertaining and cogent critique of those current strategies and rhetorics of corporate leadership and management which centre on ‘crypto-theological’ tropes of (self-)sacrifice and competitive striving. (See Philip’s great post here for some of this; and for some perceptive worries about what recent sloganeering about ‘leadership’ might really mean, see a post by classicist and commentator Mary Beard here).

The discussions after each paper were considerably enhanced by the fact that several staff and postgraduates from the School of Management joined the classicists and ancient historians throughout the event. It was also great to see so many of Classics’ own postgraduates (both the newly-arrived and more battle-hardened) taking full part and asking great questions.