‘Coalition of chaos’.

‘Strong and stable leadership’.

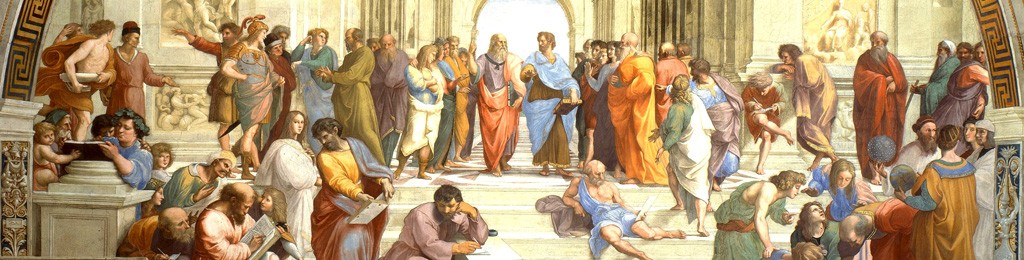

These two phrases are key slogans or ‘soundbites’ in the Conservatives’ 2017 general election campaign. They deploy ‘alliteration’, a rhetorical ‘figure of sound’ which Cicero loved to use (although he also disapproved of an excessive reliance on it). Alliteration is implicitly recognized for its rhetorical power as far back as the 5th century BCE Greek sophist Gorgias. An ancient Greek word for it is paroemion, although this label seems not to have been coined until the 1500s. Alliteratio as an actual rhetorical term also seems to derive from the rhetorical handbooks of the early modern period. [On both these points I confess to limited research and am happy to be corrected].

Alliteration gets defined in different ways these days. Some restrict it to the frequent repetition of initial consonants in close proximity to each other. Others define it more broadly as ‘repetition in the initial sounds of words that can produce echoes of phonetic similarity throughout a text’ (Fahnestock 2011). I quite like this one from the Silva Rhetoricae website: ‘Repetition of the same letter or sound within nearby words. Most often, repeated initial consonants’.

Historians and psychologists of political rhetoric talk a lot about the way in which 20th and 21st century communications have fundamentally changed the nature of political persuasion and communication by comparison with the days of Gorgias, Aristotle and Cicero. But alliteration is one device which is particularly suited to the era of ‘soundbites’ and Twitter. It seems to be more popular than ever with politicians and spin doctors.

In a book by a very experienced political speechwriter called Winning Minds. Secrets From the Language of Leadership, we get some sense of why ‘alliterative pairs’ like ‘Strong and Stable Leadership’ or ‘Coalition of Chaos’ and are so effective: ‘they reinforce a sense of balance’ (Lancaster 2015). Balanced and ordered phrasing, argues Lancaster, is something which audiences warm to at a neurological level, regardless of whether it maps on to anything meaningful or true. But alliterative phrases also create powerful impressions and associations. Jeanne Fahnestock offers examples of ‘alliterative triplets’ where ‘the repeated opening consonant helps the rhetor produce the impression of a coherent set’. She cites Lyndon Johnson: ‘So I want to talk to you today about three places where we begin to build the Great Society—in our cities, in our countryside, and in our classrooms’. In the case of ‘coalition of chaos’, it is pretty obvious what ‘coherent set’ of associations the Prime Minister is aiming to produce.

Another reason why slogans and soundbites so often deploy alliteration is that they are much more memorable than those which do not. Alliteration has been proven to work very well in aiding memory and the recall of information in educational contexts. When it comes to political messaging, then, short alliterative phrases can be the best way to get the electorate to both understand and remember what you stand for, not to mention how you want them to think about your opponents.

Soundbites and sloganeering are often decried as symptomatic of an era in which political debate and democratic discourse have become debased and hollowed out. The leader of the Labour Party is explicitly rejecting ‘the stuff of soundbites’ in this campaign. This is part of his own rhetorical claim to authenticity and to stand for a new kind of politics. But there are real risks to this strategy given the nature of modern media communications and the power of the most memorable and quotable slogans to set the terms of an electoral agenda – and to do so in favour of the party that comes up with them.

References:

Jeanne Fahnestock Rhetorical style: the Uses of Language in Persuasion (Oxford and New York 2011)

Simon Lancaster Winning Minds. Secrets from the Language of Leadership (New York 2015)