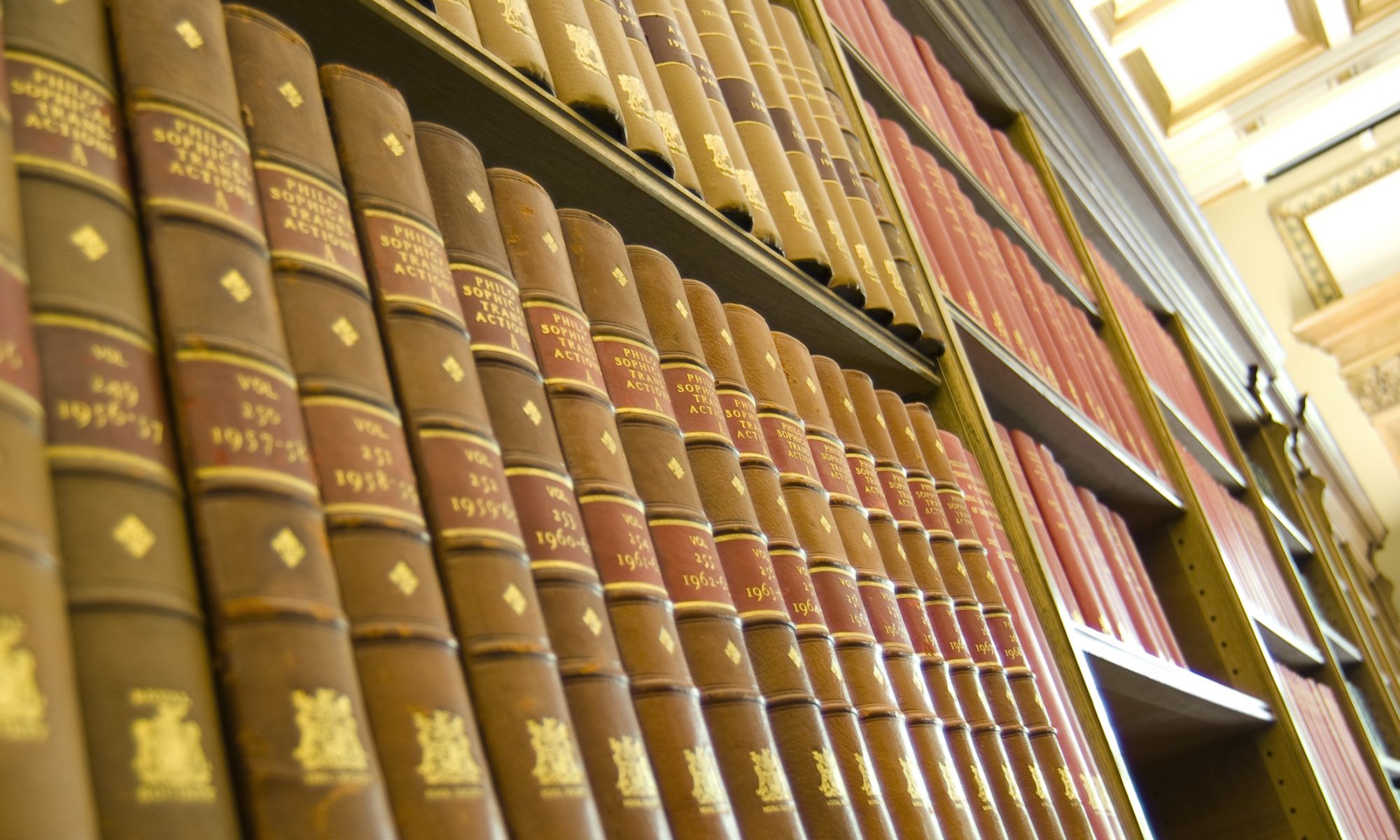

The more recent history of the Royal Society and the Philosophical Transactions.

The history of the Royal Society has received considerable attention in the last fifty years. This has largely focused on the beginnings of the Royal Society in 1660 and on the individuals who shaped the nature of science at this time, and in the period up to 1900.

We are familiar with names such as Hans Sloane (1660–1753), Robert Boyle (1627–1691), Robert Hooke (1635–1703), Isaac Newton (1642–1727), Henry Oldenburg (1617–1677) and Charles Darwin (1809–1882), to name but a few, all Fellows of the Royal Society who occupy the stage in studies of the Society in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The reasons for their fame in the history of the Society are many, ranging from the impact they had on the world of science, to the rich material that survives on their discoveries, theories and life.

Henry Oldenburg FRS, the first editor of the Philosophical Transactions.

Portrait by Jan van Cleve, 1668 © The Royal Society

The interest in the Society’s early history is rich and important, but the Society’s role in science and its communication is long and extends further than the two hundred and forty years from its formation in 1660 until 1900. There is much to know about the individuals shaping science in the early twentieth century, and while this period has received some attention, there are many more stories to tell (watch this space). But what is there to know about the even more recent history of the Society in the late twentieth century, which has had little consideration, and particularly what can we understand about its publication, the Philosophical Transactions? To provide a brief glimpse of the changes and developments the Philosophical Transactions experienced in the late twentieth century let us focus on one year, say 1990.

First let us look at what was happening in science generally around this year. A major event in 1990 was the beginning of the Human Genome Project, which started in the US and was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the sequence of human DNA. One of the findings of the project was that there are approximately 20,500 genes in human beings.

Understanding DNA sequencing was another step towards getting to grips with the nature of diseases and their effect on humans. The Philosophical Transactions Series B (Biological Sciences) was the site of early discussions about identifying human DNA sequences, including a 1988 paper by Edwin M Southern on ‘Prospects for a Complete Molecular Map of the Human Genome’. Southern discussed the appropriate form and scale of such a genome map, based on contemporary knowledge of the organization of human DNA. Southern went on in 2005 to win the Lasker Award in biology for his laboratory procedure, inventing the ‘Southern Blot’, which was the first test for fingerprinting and determining paternity, and is today used for DNA analysis in many fields of biology. In terms of its impact on our understanding of genetics, Southern’s test was just as innovative in the late twentieth century as, say, Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke’s air pump was to naturalists in the seventeenth century.

What else was happening at the Royal Society around 1990? At this time, the Society’s medium of communication was, in part, the Philosophical Transactions. This journal went through a transition in 1990: it had previously been considered to be under the responsibility of the two Secretaries of the Society, but was now assigned two editors. These editors were scientists based in external institutions (often universities) who had specialist knowledge of a field of biology or physics. Getting to grips with the ways individuals, printers and publishers maintained the journal as a leading scientific publication in the late twentieth century informs our understanding of science communication and the nature of the print trade in an age of changing media technology.

There was also an international development in 1990 that had a large impact on the communication of science by the Royal Society, and particularly on the ways in which its journal, the Philosophical Transactions, was published. Some of us are old enough to recall the impact this phenomenon had on people’s understanding of and interaction with one another and the world around them, though others may be too young to remember how influential this development really was on the generation of people who had to (or chose to) mould their practices in favour of its revelatory ways. You may wonder what I’m referring to or you may have guessed: it’s the World Wide Web and, connected to this, the popularisation of computers.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee FRS signing the Royal Society’s Charter Book, October 2002

(IM/000347 © The Royal Society)

The World Wide Web came into existence in 1990 when Tim Berners-Lee created the first web server, which was released to the public in 1991. Along with the World Wide Web, there was an increasing move towards digital/computerised systems in the communication, ordering and dissemination of information. For the Royal Society, a pivotal moment in this transformation of communication technology was the start in 1997 of electronic delivery of the Royal Society’s journals by Blackwell’s ‘Navigator’. The in-house administration of the journal also faced a change to a Windows-based computer system with personal email, and was allied with the creation of a website for Philosophical Transactions where readers and authors could access information about the journal remotely. The practice of exchanging manuscripts between authors and those responsible for compiling the Philosophical Transactions was replaced by an online and digital system of transfer and communication.

The year 1990 was part of a long history of change and variation in the Royal Society, in science, and in scientific communication. It serves as an example of the connection between science and technological developments and, significantly, reveals the importance the late twentieth century holds for our knowledge of science communication and scientific journal publishing.