Most people who have dabbled in art history, have come across Sir Ernst Hans Josef Gombrich (1909-2001). The OM CBE FBA awarded Austrian-born art historian, who became a naturalised British citizen during the Second World War and spent most of his life in the UK, grew to be one of the most important figures of the field. He did this by being a prolific author, speaker, and influential public intellectual. His most beloved and well-known books include The Story of Art, a beautiful introduction to Western art, and Art and Illusion, a groundbreaking thesis about the psychology of perception and visual culture. There is no denying his importance in the humanities, but why did he choose to publish a paper in the Philosophical Transactions in 1966?

The sixties were a time of immense change for art history, as elsewhere. Sociologists, feminists, and postcolonial theorists reshaped the methodologies, language, concerns, and debates of the discipline. Gombrich, who was born in 1909, was a pioneer in terms of theory. His important contribution to the study of perception in art, Art and Illusion from 1960, would have a profound effect on aesthetics, semiotics and other postmodern fields of study. The book was one of Gombrich’s many journeys into scientific language and interdisciplinary studies. In it he argued for the importance of ‘schemata’ in exploring and analyzing works of art, posing the theory that artists learn to represent the world through their knowledge of previous artists. Thus, Gombrich wrote, representation is always done using stereotyped figures and methods. The book made Gombrich more known than ever before (he was already relatively well known for the popular and best-selling Story of Art), but art historical historiography has generally overlooked how this fame stretched beyond the humanities and into the sciences. What makes the Philosophical Transactions paper so interesting, is that it is not only a theoretical exploration of ritual in art, but also includes political material and thoughts on the Cold War.

By the time Gombrich decided to get involved with the Royal Society, he had been debating and discussing Art and Illusion for six years. His writings had already started to have an effect on art history teaching at universities, introducing the idea of a more ‘scientific’ approach to the study of artworks. Previously, art history had been largely based on the idea of connoisseurship, the canon of masterpieces (by mostly white male artists), and the idea of the ‘zeitgeist‘. Gombrich famously argued in Story of Art: “There is really no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” His ideas were grounded in the theories of the philosopher of science Karl Popper, and were thus also connected to the sciences.

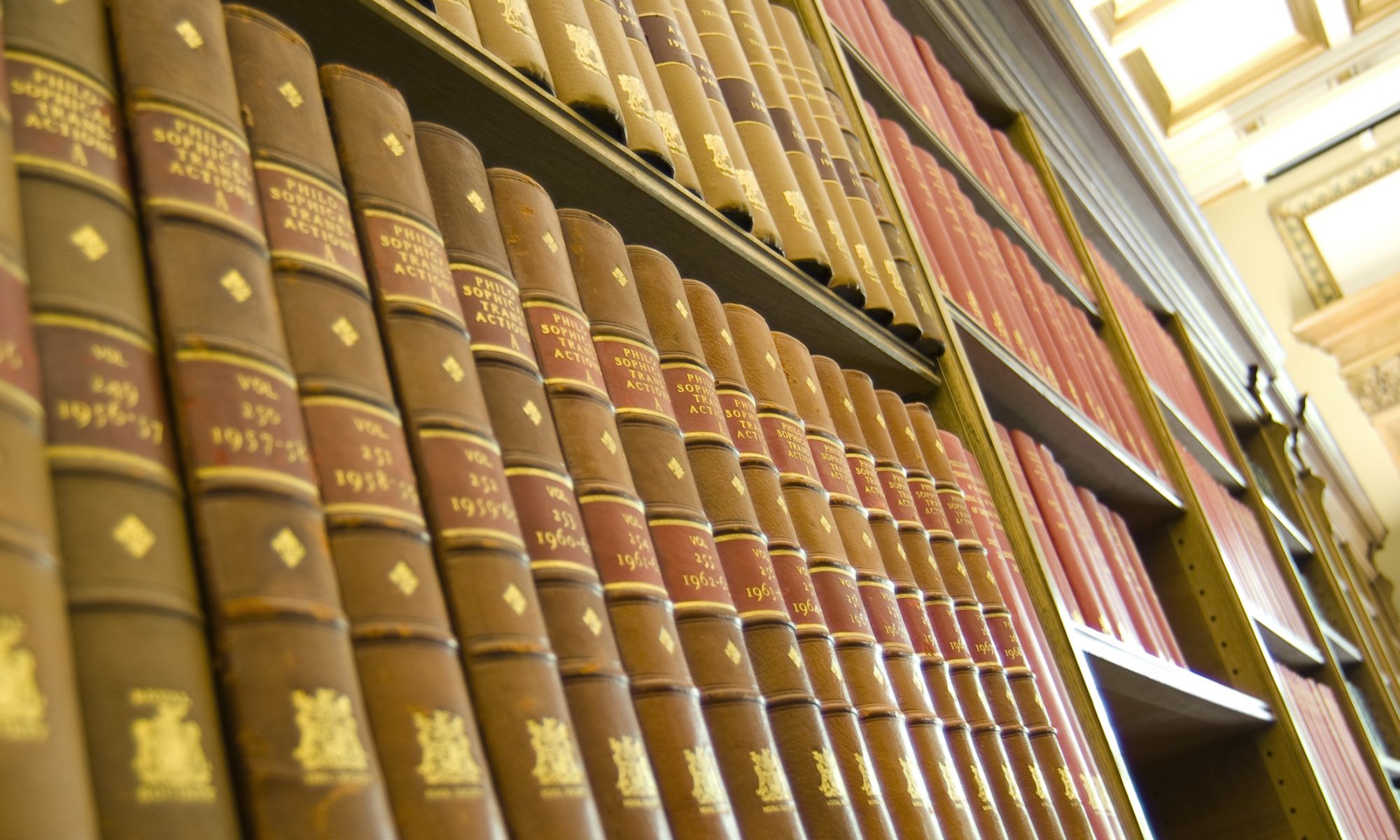

The Philosophical Transactions have, throughout their over 350-year long history, usually been a place for science and natural history. It is therefore odd that Gombrich, however well versed in the philosophy of science, should chose to publish anything with the Royal Society. The paper is written in a relaxed, unpretentious style, with few specialist words and an engaging tone. Gombrich was recognized as a great and popular writer, who strove to make complex theories and concepts readily available for any reader; from child to specialist, from students to professors. The tone is in this instance extra casual, probably because the paper is a transcript of an oral presentation. He starts: “I hope I may dispense with the ritual of an introduction and plunge in medias res…” Little information survives of the meeting, but an educated guess would be that Gombrich read his paper aloud sometime during 1965 or 1966, before publishing an edited version with added bibliography in December of 1966. The Royal Society had many meetings were papers were read out, in fact this was the basis of the historical Philosophical Transactions, and still takes up some space in the modern journal. However, unusually, Gombrich’s paper was either not peer reviewed, or it was sent out to another specialist body during the year. Either way, no peer review report survives in the Royal Society’s archives.

The paper itself, “Ritualized Gesture and Expression in Art” is symptomatic of the type of ideas that interested Gombrich at the time. The idea of ritual, expression and emotion was a large part of his understanding of schemes and styles in art and visual culture. The paper is richly illustrated with black and white images from the history of Western Art, in order to illustrate his arguments about stylized and ritualized expressions in art. His examples include Käthe Kollwitz’ anti-war posters, van Eyck’s “God the Father”, Russian Revolutionary propaganda posters, details of sculptors, Egyptian art, and Rembrandt’s sketches.

This wide variety of art spanning decades all serve to underline the idea that artists copy each other (knowingly or not) and ritualize movements and emotions. He argues that although most viewers understand the emotion of a raised fist in a Russian Revolutionary propaganda poster, few of us would actually use that movement if pressed to act the same way (i.e. lead a revolution, as the figure of Lenin seems to be doing in the example). The illustration of the raised fist is thus both a symbol we understand with empathy, and a unrealistic representation of an imagined reality:

This raises the whole vexed question of the relation between the gestures we see represented in art and those performed in real life. It is a vexed question for two reasons, one because in many cases art is our principal source of information about gestures and secondly because art arrests movement and is therefore restricted in the gestures it can show unambiguously. You cannot paint even the shaking of the head we use in the West for ‘no’.

In his paper, Gombrich thus proposed as his principle hypothesis that as far as gesture is concerned the schema used by artists is generally pre-formed in ritual, and that art and ritual cannot be separated. One might think of the concept of simulacra too; a copy which is not true to the original, or which creates a fake sense of reality. Gombrich used the example of applause (imagine here being in the audience of his lecture at the Royal Society!):

We may be happy in the ritual of applause at the end of a lecture or concert, but when we stand face to face with the performer we are bothered to hear everyone say, ‘thank you for a most interesting lecture’. We are, precisely because it is a ritual and we know that it is performed after good and bad lectures alike. We try as we approach the lecturer to make our voice more charged with symptoms of sincere emotion, we press his hand in raptures, but even these tricks are quickly ritualized and most of us give up and lapse into inarticulacy.

As usual, Gombrich was not only talking about himself here, but making a wider point about the dangers of ritual. The Judas Kiss, he reminds us, looks like a loving embrace, but is in fact an attack. Similarly, the waves and smiles and movements of our politicians make it difficult to spot actual emotion. In art history, such aesthetic problems had usually been treated as theoretical splits between ‘sincere’ versus ‘theatrical’ expressions. But Gombrich argued against this depoliticized view: “Both the rhetorical and the anti-rhetorical, the ritualistic and the anti-ritualistic are in a sense conventions. Indeed what else could they be, if they are to serve communication between human beings?” If we believe too much in ritual, whether in art or politics, Gombrich reminded his readers, we stand in danger of loosing creativity:

It may have been liberating for Jackson Pollock to break all bonds and pour his paint on the canvas, but once everybody does it, it becomes a ritual in the modern sense of the term, a mere trick than can be learned and gone through without emotion. In trying to avoid this dilemma we get anti art and anti-anti-art, till we are all in a spin of ritualistic innovation for its own sake.

Again, Gombrich had a wider, political point to make, which comes across clearly in his conclusion:

The dilemmas that underlie this crisis are real enough, I believe. We cannot return to the anonymous ritual of mass emotion as we are enjoined to do on the other side of the Iron Curtain. But we can, I hope, face these issues and learn from behavior that neither the total sacrifice of convention nor the revival of collective ritual can answer the needs of what we have come to mean by art.

Unfortunately, no records of the debate that followed at the Royal Society survive. But we can perhaps imagine what the attending scientists and fellows would have made of the passionate art critic as he laid out his scientifically inspired theory about emotions, ritual and politics. Whatever may have happened after Gombrich received his ‘ritualistic’ applause, we can at least celebrate with genuine curiosity this interdisciplinary moment in the history of the Philosophical Transactions.