By Robert Crawford

(Download)

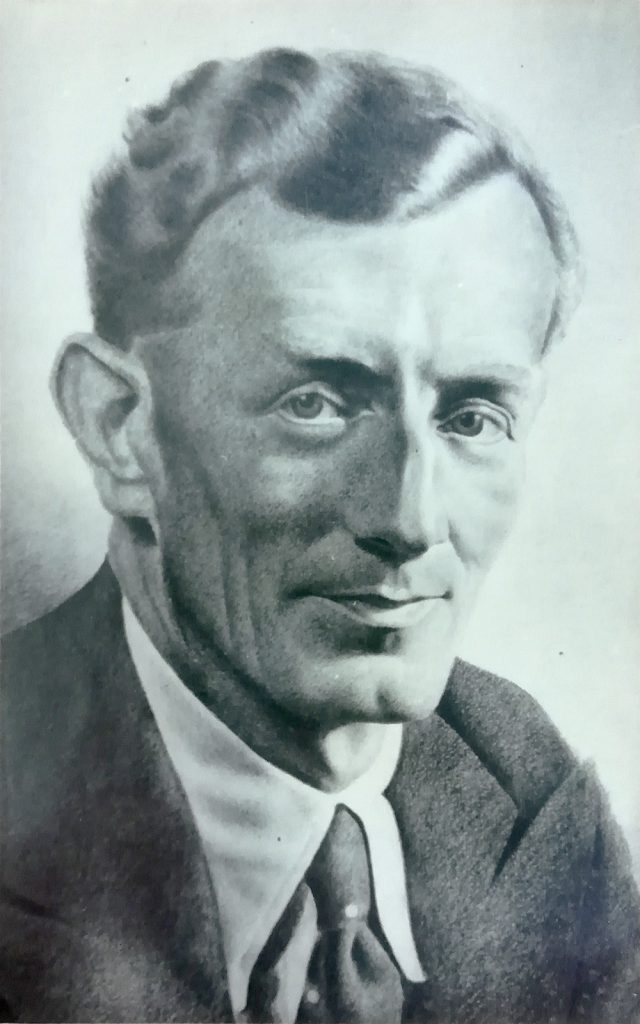

Joe Corrie wrote one indelible poem, ‘The Image o’ God’. Set out as the title piece and opening work in his first pamphlet as well as the initial poem in his 1937 Porpoise Press volume, The Image o’ God, it clearly mattered a lot also to Corrie and to his editors, most famous of whom was T. S. Eliot.

[1] Calling Corrie ‘the greatest Scots poet since Burns’, Eliot thought it right to leave ‘The Image o’ God’ in the most prominent position in Corrie’s book, but in 1937 several reviewers, including those in the Scotsman and the Times Literary Supplement, failed to single out this particular poem. Still, in its reach, music, diction and tone it is Corrie’s best. ‘The Image o’ God’ shares with his sharpest work in Scots a vital quality of direct vernacular attack, but it has much more than that.

This short, four-verse poem begins and ends with the commandingly resonant phrase ‘The Image o’ God’, which also forms part of its third line. A good number of Corrie’s poems are suffused with biblical imagery as well as political bite, and for generations (like Corrie’s) steeped in the biblical words of the Authorized Version, the title ‘The Image o’ God’ would have brought to mind the creation story in the Book of Genesis: ‘And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.’ (Genesis, I.26) Corrie’s poem deals with power relations, but instead of having ‘dominion’ over the ‘creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth’, the poem’s speaker has become that creeping thing, ‘Crawlin’ aboot like a snail in the mud’.[2] Indeed, ‘Crawlin’’ is more debased than ‘creeping’, and, in a poem of insistent physicality, ‘mud’ is more muckily offputting than mere ‘earth’. Corrie’s language here works hard, and subtly. His snail crawls not ‘alang’, which would have suggested a clear direction, but ‘aboot’, implying directionlesness. In its resonances and precise word-choice, this poem packs a punch from the very start. Beginning with a stressed syllable, most of his lines go on impacting purposefully on the reader or listener.

Though Genesis is invoked by the title and opening image, the exact phrase ‘the image of God’ is not used in the Old Testament creation story. Instead, it is deployed in the New Testament, at verse four of chapter four of St Paul’s second epistle to the Corinthians, a chapter full of images of light and darkness. There we hear of ‘the light of the glorious gospel of Christ, who is the image of God’. Where the New Testament Christ, giving himself to redeem mankind, is associated with light, in Corrie’s poem a man-snail coated in coal-dust and sweat (‘Covered with clammy blae’) speaks of how ‘I gi’e my life’ in the very different conditions of early twentieth-century underground mining.

If the phrase ‘The image of God’ is biblical, then it was most famously deployed in English poetry by John Milton in Paradise Lost, where, retelling the story of Genesis, the poet writes (in Book VII, lines 524-8) of how God

… formed thee, Adam, thee O man

Dust of the ground, and in thy nostrils breathed

The breath of life; in his own image he

Created thee, in the image of God

Express, and thou becamest a living soul.

In Corrie’s poem, though, it is the ‘blae’ of coal-dust that coats the sweating, snail-like man ‘Gaspin’ for want o’ air.’ The way Corrie’s poem runs counter to biblical and Miltonic imagery, while alluding to them, powers it with an almost blasphemous charge.

Given currency in poetry by Milton, the phrase ‘the image of God’ was used by several poets in the generations before Corrie. Elizabeth Barrett Browning has a poem called ‘The Image of God’; and, notably, in the later nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries the phrase could be used in the context of defacing God’s image. So, for instance, Lady Wilde (mother of Oscar) in her poem about Ireland’s sufferings, ‘The Exodus’, writes of military casualties ‘Strewn like blasted trees on the sod, / Men that were made in the image of God’; while, later, in ‘The Temple’, a poem from her 1915 collection of World War I verse, Flowers of Youth: Poems in War Time, another once popular Irish poet, Katharine Tynan, asks the question ‘What brute / Dares deface the image of God?’[3] While it is quite possible that Corrie, some of whose own early poems deal with World War I and who was friendly with at least one admirer of Katharine Tynan’s work, had read this particular Tynan poem, it seems unlikely that he knew the whole history of the phrase ‘the image of God’ in English poetry; but his poem ‘The Image o’ God’ is part of a discernible trajectory.

Corrie’s Scots vernacularizes this trajectory, without sacrificing access to biblical and Miltonic resonances – which gives his poem all the greater reach. The use of ‘o’’ instead of ‘of’ in the title emphasizes a speaking voice, and the poem is throughout vernacular and performative as well as subtly innovative: the phrase ‘clammy blue’, for instance, may have been used before in English prose and in speech, but Corrie appears to be the first person to bring it into verse, making the most of its rebarbative vividness. In revising the poem after its early publication, he (or his editor, presumably with Corrie’s consent) alters the word ‘Me’ that begins both line three of the poem and the poem’s penultimate line, so that it now reads ‘ME’ at line three, and, even more emphatically ‘ME!’ at the start of the second-last line.[4] That capitalization adds power to the kick of the stressed syllable at the start of the line, and gives the reader a clear cue about how to perform the poem when voicing it. It is clearly a poem that comes from voice and is for voice, as well as being, especially in its title, alert to textual resonances.

If the piece were prose, we might expect the third line to read, ‘Me, made in the image o’ God’, but Corrie wants the stressed syllable that begins the word ‘after’, so he does not simply use the preposition ‘in’. The effect of this word-choice is subtle and subliminal: for a twentieth-century or twenty-first-century ear, it’s hard to hear the words ‘after the image’ without the ghosting-in of the more familiar term ‘after-image’. ‘After-image’ was a compound word that had entered English in the generation before Corrie’s, and which is still in use today; after-images can be both literal and metaphorical, referring (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it) to an ‘impression retained by the retina of the eye, or by any other organ of sense, of a vivid sensation, after the external cause has been removed.’ Is the speaker of Corrie’s poem an ‘after-image’ in a world from which God has been removed? It’s hard to know how much credence we should give to the Christian God invoked by the politically radical poet, but that may be part of the point of poems like this one. Is the idea of man being made in the image of God laughable, or is it simply what some men have reduced other men to that makes it seem laughable that man should have been made in the image of God? Corrie, who was familiar with (and sometimes mentions) cinema, would have known all sorts of after-images as well as knowing the term ‘after-image’ itself. The point is not that he is consciously intending readers to think of the expression ‘after-image’; it is simply that when a poet is operating at full capacity, as Corrie is in ‘The Image o’ God’, his language acquires a reach that may go beyond conscious design, triggering deep connections between words to make resonances that enrich the poem’s acoustic.

This poem has a great acoustic. The repetition of the title, and of lines three and four, which also become the very last lines of the poem, box the work in, making it a kind of sound-cage within which the speaker exists. This effect of acoustic claustrophobia intensifies the smothering sense of being ‘’neath a mountain o’ stane / Gaspin’ for want o’ air’, and of being boxed in by the social system represented by ‘the gaffer’ and ‘the Nimmo squad’. Though it may need explanation for a modern audience (who have to be told that Sir Adam Nimmo was a coal company supremo who argued, especially around the time of the 1926 General Strike, that miners’ wages must be reduced; Nimmo was loathed by the miners, not least in Joe Corrie’s Fife where he had major financial interests), Corrie’s use of the phrase ‘the Nimmo squad’ is inspired because it situates the poem incisively within a particular political history of class conflict, giving it all the more bite.[5] ‘Squad’ — which may refer to the coalmine-owning Nimmo family as a whole, but probably refers to a team of miners working for Nimmo — sounds militaristic (as in ‘squad-drill’) and has a confrontational edge to it (think also of ‘awkward squad’); helpfully, and perhaps ironically, it also rhymes with ‘God’. The rhyme is not just useful, but intensifying; when we examine the poem’s rhymes, they are striking because they repeat sounds even more often than might be expected: the first stanza’s rhyme of ‘mud’ and ‘God’ is picked up again in the third stanza’s ‘mad’ and ‘lad’, and then again in the final stanza’s ‘squad’ and ‘God’; the vowel in the first stanza’s end-rhyme words ‘blae’ and ‘tae’ is picked up in all the end-rhyme words of stanza two (‘stane’, ‘air’, back-bane’, ‘sair’), then again in the ‘day’ and ‘tae’ of the final stanza. All this intensification and repetition of rhyme heightens a sensation of being caged-in when the poem’s soundscape is encountered. So does the repetition of ‘Half starved, half blin’, half mad’ (there’s something hauntingly odd about having three halves), and so does the poem’s use of alliteration and other, subtle kinds of vowel music: ‘Me, made’. Though it is very, very hard to use exclamation marks well in poetry, Corrie does so in this work, further heightening its vernacular, performative intensity.

Even his use of ‘Jings!’ – a word used only occasionally in American dialect verse and in Scots before this date – emphasizes both the vernacularity and the exclamatory force that opens so many of the lines.[6] Corrie, here, is a poet able to exclaim yet also able to balance between tones: just how are we to read those words, ‘it’s laughable, tae’? Do they mean it’s a terrible cosmic, or at least class-ridden joke, or do they indicate that only by laughing at the situation can the speaker get through it? Or do they imply both? I think they imply both, and that the poem is all the stronger, all the more hauntingly unsettling and powerfully voiced, for that rich ambiguity.

‘The Image o’ God’ was written when Joe Corrie was at the height of his game. Still, without further work, it can’t be dated exactly. Even the date of its first appearance in book or pamphlet form is uncertain. The 1937 Porpoise Press edition of The Image o’ God contains a note saying that ‘This collection of poems supersedes a pamphlet called The Image o’ God, published for the author in 1926’, but Linda Mackenney, who seems to have researched Corrie more thoroughly than anyone else, dates this pamphlet (which, issued by the Forward Press in Glasgow, bears no date of publication) to ‘1927/8’.[7] Mackenney’s dating accords with the 1937 Scotsman reviewer’s statement that ‘It was about nine years ago that a thin, unobtrusive pamphlet, containing eighty-eight poems by Joe Corrie, was published in Glasgow’.[8] Eighty-eight poems is a lot of work to put in a ‘pamphlet’, and a smaller number of poems than appear in the 1937 Porpoise Press ‘book’. The surviving copy of the now rare, but once widely sold ‘pamphlet’ in the University of St Andrews Library is in fact a slim hardback volume, bearing simply the title Poems on its title page, but the title The Image o’ God And Other Poems By Joe Corrie on its front cover; it does not appear to have been rebound.

As with so much to do with Corrie, the documentation and scholarship here is sparse; but it’s clear that the poem ‘The Image o’ God’ dates from the period around and probably just after the General Strike. This is when Corrie wrote not just his best poem but also In Time o’ Strife and his novel Black Earth (which was serialised in Forward from June until September 1928, though not published in book form until 1939).[9] Evidently the General Strike, however oppressive, was a spur to his writing and publishing, but other conditioning factors may have led to his substantial achievements at this precise period. In particular, one of these is his closeness to Hugh Roberton.

Twenty years Corrie’s senior, the Glaswegian Roberton was a self-taught conductor, composer, poet, and dramatist, most celebrated throughout the first half of the twentieth century for his conducting of the Glasgow Orpheus Choir which drew principally on working-class singers from Glasgow’s Rottenrow and East End.[10] It was Roberton who wrote the foreword to the Forward-published pamphlet The Image o’ God, which itself contains a poem, ‘Song of the Orpheus Choir’, headed ‘(On hearing the world-famous Choir at Kirkcaldy)’.[11] Corrie’s awkward poem expresses intense excitement at the way the choir comes ‘with the rapture of youth to the aged’, bringing ‘the call of the free to the caged’. Characteristic of this poem’s awkwardness is that it is hard to know just how Corrie thinks we should pronounce the words ‘aged’ and ‘caged’ to get sense to match rhyme; but his enthusiasm for the Glasgow choir is clear. Roberton’s foreword explains that ‘Some years ago, after an Orpheus concert at Kirkcaldy, a young man came forward to shake hands. That was my first meeting with Joe. I liked him.’[12] Exactly when this encounter took place is unclear; surviving concert programmes suggest that the Orpheus Choir visited Kirkcaldy at least annually (in November 1922, for instance, they sang in the Adam Smith Hall there), but, soon after meeting, Corrie and Roberton were corresponding, and Corrie was visiting Roberton at home.[13] Roberton’s background was linked to the Independent Labour Party, for whom he sometimes lectured on such subjects as ‘Music and Democracy’, and which was itself linked to Forward Publishing.[14] Though Roberton’s choir’s origins dated back to 1901, by the mid-1920s it was still regarded as innovative and its fame was widespread. Its repertoire included many Scottish songs (not least by Robert Burns) as well as religious music; but its and Roberton’s most celebrated piece was probably his arrangement of a poem by Katharine Tynan about ‘the Lamb of God’, ‘All in the April Evening’, which Roberton had set to music in 1911 and which can still be heard in his setting by anyone who cares to search for it on the internet. A long 1925 article in the Musical Times detailed Roberton’s achievements, making clear not just his substantial musical and administrative gifts, but also that he was a poet and dramatist in Scots and English who had recently published one-act plays.[15] For Joe Corrie, the self-taught Roberton, an influential musician, poet and dramatist, was the ideal contact.

Roberton’s one-act play Christ in the Kirkyaird had been

performed by the recently founded Scottish National Players in 1921, and published

by William Collins in 1922 along with another of Roberton’s plays, Kirsteen,

whose cadences and milieu are strongly influenced by the Celtic Twilight school

headed by Yeats, Katharine Tynan, and others.[16] When in 1927 the ‘Duologue in Lowland Scots’ Christ in the Kirkyaird was broadcast by

the BBC in Glasgow, Roberton himself read the part of

John Christie the gravedigger and the other part, that of gardener Peter

Snodgrass, was read by Roberton’s friend and fellow

man of the theatre Joe Corrie.[17] By this time Corrie had had his own early plays The Poacher and The Shillin-a-Week Man performed by the Scottish National

Players in 1926 and 1927 respectively.[18] In Roberton’s Christ

in the Kirk Yaird Corrie was taking part in a

play which brought together the figure of Christ with modern man in the context

of digging, and of what Roberton calls elsewhere

‘religious arguings’.[19] It seems likely that it was Roberton’s friendship and

influence that helped Corrie make his breakthrough with the Scottish National

Players and which may be bound up with the shaping of ‘The Image o’ God.’ To

argue this is not to say that Corrie was not responsible for his own successes;

nor is it to suggest that readers should be discouraged from setting Corrie’s

best poem alongside work by other contemporary writers, whether that of Hugh

MacDiarmid or John Buchan (whose popular 1925 novel John Macnab, like Corrie’s best poem, uses the phrase ‘Howkin awa’’ close to mention of

‘crawlin’ like a serpent’) or beside the work of

European writers contemporary with this Fife poet who would soon accept invitations

to Russia and Germany where his fiction and drama would be translated.[20] However, his friendship with the musician and author of Christ in the Kirkyaird may help explain

why (even though the Scottish National Players would turn down In Time o’ Strife) this was the period

when, fired up by his experience of circumstances surrounding the General

Strike, Corrie made his breakthrough as a writer and wrote his finest poem, one

which, with artistry, acoustic reach, and magnificently unsettling political

edge, fuses the life of the modern miner with that of ‘The Image o’ God.’

[1] See Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue, ed., The Poems of T. S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 2015), 2 vols., II, 173; Eliot’s 9 March 1937 letter to Corrie about the editing (now among Corrie’s papers in the National Library of Scotland) makes clear that the ordering of the poems was Corrie’s, and that Eliot was happy with it; Corrie thanked Eliot for ‘all the trouble you have taken in selecting the poems for “The Image o’ God”’ (quoted in Alistair McCleery, The Porpoise Press 1922-39 (Edinburgh: Merchiston Publishing, 1988), 88); Eliot’s praise of Corrie is quoted, e.g., in the entry for Joe Corrie on the website of the Scottish Poetry Library http://www.scottishpoetrylibrary.org.uk/poetry/poets/joe-corrie

I suspect Eliot’s phrasing was used as a ‘blurb’ on the dust-jacket of the Porpoise Press edition of The Image o’ God, but I have not been able to locate a surviving dust-jacket.

[2] Joe Corrie, The Image o’God(Edinburgh: Porpoise Press, 1937), 9; the poem is reprinted in several modern anthologies, e.g., Meg Bateman, Robert Crawford and James McGonigal, ed., Scottish Religious Poetry (Edinburgh: St Andrew Press, 2000), 230. Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are from the Porpoise Press text.

[3] Speranza (Lady Wilde), Poems (Dublin: James Duffy, 1864), 55; Katharine Tynan, Flower of Youth: Poems in War Time (London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1915), 29.

[4] This comparison aligns the Porpoise Press text of the poem with the earlier text in Joe Corrie, The Image of God [whose title page bears the title, Poems] (Glasgow: Forward Publishing, n.d. [?1928]), [7].

[5] On Sir Adam Nimmo, see his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (hereafter ODNB); also Christopher Harvie, No Gods and Precious Few Heroes: Twentieth-Century Scotland, 4th ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 9.

[6] Though present-day readers may associate ‘Jings!’ with the comic strip ‘Oor Wullie’ (whose origins date from 1936) and The Beano (first published in 1938), Corrie’s poem predates such associations and still has the strength to hold its own.

[7] See p[5] of the Porpoise Press edition; Linda Mackenney, ed., Joe Corrie: Plays, Poems and Theatre Writings (Edinburgh: 7:84 Publications, 1985), 17; Paul Malgrati (private communication, October 2018) tells me that the poem ‘The Image o’ God’ was first published in Forward.

[8] ‘Poems in Scots’, Scotsman, 26 April 1937, 15; the reviewer in ‘Poetry’, Times Literary Supplement, 22 May 1937, 398, follows the dating given in the Porpoise Press edition.

[9] Joe Corrie, In Time o’ Strife: Original Script and Adaptation by Graham McLaren (London: Bloomsbury, 2013); on the earlier publication of Black Earth, see H. Gustav Klaus, ‘Individual, Community and Conflict in Scottish Working-class Fiction, 1920-1940’, in Scott Lyall, ed., Community in Modern Scottish Literature (Leiden: Brill Rodopi, 2016), 48.

[10] For Roberton’s biography, see ODNB.

[11] Corrie, The Image o’ God (Forward Publishing), 32.

[12] Corrie, The Image o’ God (Forward Publishing), [5].

[13] See, e.g., The Program and Book of Words of Concerts given by the Glasgow Orpheus Choir in the Adam Smith Hall Kirkcaldy on Saturday 1th November 1922(Kirkcaldy, 1922) and The Concerts of the Glasgow Orpheus Choir, Adam Smith Hall, 24 November 1923 (Kirkcaldy, 1923) [concert programmes].

[14] Music and Democracy, Lecture delivered in the Metropole Theatre, Glasgow, under the auspices of the Independent Labour Party, On Sunday 22 December 1912 by Hugh S Roberton (Conductor Glasgow Orpheus Choir). (Glasgow: Reformers Bookstall Ltd., [1912]), Glasgow University Library Special Collections, MS Gen 573/4/3.

[15] Harvey Grace, ‘The Glasgow Orpheus Choir’, Musical Times, 66.987 (1 May 1925), 401-5.

[16] See Karen Anne Marshalsay, The Scottish National Players: In the Nature of an Experiment, 1913-1934, PhD thesis, University of Glasgow, 1991, 2 vols, II, 3 (Appendix One).

[17] ‘Glasgow – 5 SC’, Scotsman, 15 December 1927, 14.

[18] Marshalsay, The Scottish National Players, II, 3; in 1928, around the time Corrie came to live in Mauchline, Roberton spoke to the recently founded Burns Club there on ‘The Common Man and Poetry’ (see Ian Lyell, ‘Corrie revival is to be welcomed’, Glasgow Herald, 4 October 2013, Letters.

[19] Hugh S. Roberton, Kirsteen: Two Plays (London: Collins, 1922), 20.

[20] John Buchan, John Macnab (1925; rpt. London: Penguin, 1956), 67; though a German version of In Time o’ Strife was performed in Leipzig in 1930 by the Collective of Proleterian Actors, the German text does not appear to have been published; Corrie’s visit to the Soviet Union was linked to the publication of Posledniiden’ (Moscow and Leningrad: Zemli’a’i Fabrika, 1930), a translation of Corrie’s The Last Day by Marka Volosova (in 1932 the same work was published in Yiddish in Kiev); later, in 1959 a Russian translation of Hewers of Coal was published as Uglekopy.