By William Hershaw

(Download)

by The Bowhill Players and Fife Council,

covering songs of Joe Corrie set to new music.

Jimsie

A clever lad was Jimsie at the schule,

The minister’s son could never win the prize,

The maister-and the maister was nae fule,

Said Jimsie, gien a chance, was shair tae rise:

His pentins yet are in the maister’s neuk,

Gowanes and roses o a sunlit day,

But Jimsie slaves for coppers doon the “dook,

A drawer o wealth for ithers tae display:

He never has the pencil in his hand,

Unless tae mark a coupon or a horse,

For oors each nicht doon at the lamp he’ll stand,

Tossin for pennies, and losin wi a curse.The minister’s son, I heard the ither day,

By Joe Corrie: Poems, Forward Publishing, 1928.

Was makin straucht tae be an R.S.A.

My engagement and connection with Joe Corrie’s work derives from teaching it in secondary schools and from devising teaching and learning materials based on his poetry and plays. I can claim further “hands on” experience through having performed Corrie’s poems and songs as the founder of the reformed Bowhill Players and through curating the Hewers of Verse and Coal exhibition at the Lochgelly Centre between May and August in 2018. The following paper is not an attempt at a definitive academic statement regarding particular aspects of Corrie’s work but rather a series of accounts, observations, opinions and ideas about Corrie’s educational relevance and legacy, literary and otherwise. These observations have been derived from my personal connection with his work. I write as an avowed and subjective enthusiast.

I am indebted to Donald Campbell, playwright and Scottish theatre historian who explains in his book Playing For Scotland, a History of the Scottish Stage 1715 -1985 (Mercat Press, Edinburgh, 1996) how Joe Corrie created a new audience for the Scottish theatre by writing his play In Time O Strife. The eventual rejection of the play in 1927 by the Glasgow based Scottish National Players Reading Committee resulted in Corrie forming what would eventually become The Bowhill Village Players, his own company with the remit of performing his own plays. Initially, The Players performed within the diaspora of Fife mining villages in local halls, institutes and Gothenburgh taverns and pubs before In Time o’ Strife was “discovered” by theatrical agent and actor Hugh Ogilivie who immediately recognised its potential. The Bowhill Village Players turned professional and became The Fife Miner Players. In Time o’ Strife, along with other Corrie plays such as The Poacher and The Shillin A Week Man, were performed across Scotland and later the UK in mainstream theatres to audiences of thousands. This success lasted until the early thirties and the advent of films with sound.

In In Time o’ Strife Corrie had drawn on his own experience in writing a play about the Smith, Pettigrew and Baxter families coping with the economic, moral and political pressures that the Miner’s Strike of 1926 imposed on both communities and individuals. Corrie had worked in pits both below and above ground since being forced to leave school at fourteen. Mainly self-educated through attending workers’ educational classes and reading whatever came his way, Corrie had been writing a column for the Miners’ Reform Newspaper since 1921 and was considered a political agitator by some due to his socialist stance. He had already published poems in The Lochgelly Times as well as developing his interest in drama both as a writer of one act plays and through involvement with The Auchterderran Dramatic Club. From the outset he wrote about the world of mining communities that he knew.

As Campbell explains, the audience who came to see In Time o’ Strife were neither middle class nor regular play goers familiar with the standard repertoire of the day, although many would have been familiar with the contemporary music hall tradition. It is difficult for us to envisage what this must have been like. This audience were coming to see a play written about themselves, based mainly on events they had recently experienced and featuring characters who spoke their language of Fife working class mining Scots. This audience would have readily identified with the characters, setting, themes and the recent political turmoil presented in the play. All of this would have been unexpected, innovative and groundbreaking at the time. Although fifty years have passed since Corrie’s death in Edinburgh, and the shock effect of his writing on his first audiences has long gone, I would argue that the play and much of Corrie’s poetry and shorter dramatic works retain their relevance, particularly for the generations who retain a link, either familial, emotional, geographical or political with Corrie’s original audience. This close identification and empathy expressed in Corrie’s work with a particular section of society is also the reason why Corrie has suffered a lack of critical attention or acknowledgement as an important writer, particularly in Scotland. Today’s symposium is welcomed as a first step toward redressing this.

What exists in the form of Corrie’s comments, interviews and letters suggest that he felt a strong empathy with the community he was writing for and about. Almost everything he wrote is driven by this moral/humanistic imperative. Campbell quotes Corrie publicly expressing the view that contemporary dramatists had lost sight of something he considered to be an obligation. Corrie regarded playwrights such as Sean O’Casey as failures for their pessimistic outlook and inability to provide their audiences wityh hope for a better political future. Famously, he described his job as being to offer his audience both hope and entertainment on a dreich winter’s night in a typical Fife mining village. To achieve this while also presenting objective truth in a realistic context is a difficult balancing act. Corrie’s characters do not always dwell on lofty themes. Minutes can pass with a character looking for a pound of sausages, finding a bookie’s line or singing a sentimental Burns song. Corrie sympathises with and understands his constituency and the trivia of their lives and the pathos of their small triumphs are given a full airing along with their ultimate tragedies. He never grudges hard pressed folk their dram, their gramophone, their bet, their fag or a pair of fashionable shoes so he puts all this into his plays. He feels that the economic exploitation they endure absolves them from not knowing about Russian novelists or Turkish philosophers. While it is true that he is well aware of wasted human potential, he is a realist to the core. All the characters in In Time o’ Strife are subject to pressure. Agnes Pettigrew’s dies due to starvation. Tam her husband, is driven to alcoholism. All the characters suffer greatly in one way or another. It is Jock Smith who sums up their predicament and also Corrie’s view as well:

“There’s naebody escapin the strike, Jenny. We’re a’ gettin a blow o some kind. But we’re learnin and someday we’ll mebbe get our ain back.”

In Time o’ Strife, Act Two, page 35: Bloomsbury Methuen, 2013

Corrie’s empathy and humanistic view did not sit well with some. Despite his left wing reputation, he is not a doctrinaire Marxist and Macdiarmid was ambivalent in his support for him. From Corrie’s point of view, to paraphrase, it would have been “Not Dunbar, Burns!” And he sits closer to Hamish Henderson’s Freedom Come All Ye than he does to Third Hymn To Lenin. Throughout his plays he shows that impoverished though the miners may be they still want and deserve a good life and the material benefits that come with it. At the same time, by advocating a practical socialism and by condemning the bourgouise values of the Scottish National Players, it cost him dearly in terms of later patronage and recognition. As a writer he is interested in realism and portrayal of truth and this can sometimes lead to over simplification. From a critical point of view this means that Corrie can be an awkward and even thrawn writer to pigeon hole. But why would we want to? If Corrie can clarify his message to the point where it withstands analysis, then he considers his job well done. So, we should be wary of making comparisons and look at his work for what it is. For he is there, and he was the first and therefore should and cannot be ignored. When Gregory Burke wrote Black Watch and presented young soldiers as they really are in terms of behaviour, language and psychological motivation he was drawing directly, even if subconsciously, on a tradition that Corrie had established many years before him. The same can be said for Irvine Welsh.

The notion that a symposium would have been held to examine his life and work in 2018 may have caused Corrie some wry amusement in much the same way that the biblical comparison between Man and God did.

By the time Corrie died in 1968 the mining industry in Fife was also declining. In Time of Strife was revived by the 7:84 company during the final miner’s strike in 1984. It was re-imagined by the National Theatre Company of Scotland in a version by Graham McLaren in 2012 that played to a TV back drop of Thatcher, MacGregor and the BBC coverage of Orgreave Colliery. At this time also, writer and director Robert Rae was filming The Happy Lands with a script based on an adaptation of In Time o’ Strife. At times when communal values are threatened Corrie’s work resumes its relevance. Corrie was committed to the idea of a progressive society as opposed to the individualism encouraged by the likes of Margaret Thatcher and successive Tory and Labour Governments. Picasso said,“How can an artist not possibly show any interest in other people but put on an ivory indifference and detach himself from the life which he has received so abundantly? No, painting was not invented to decorate houses. It is an instrument of war for attack and defence against the enemy.” Corrie would have endorsed this.

Although Corrie’s original audience has long died out as has the coal mining industry, the communities themselves remain although greatly changed. Have the culture, the moral and political values and the language of Corrie’s time continued? Robert Rae attempted in his Happy Lands film to illustrate that they have by auditioning an entire cast of local amateurs, most of whom had family connections with the Fife mining communities involved in the ’26 Strike. The result is a unique work of art in its authenticity, commitment and emotive power. In some cases, the actors are playing the roles of their grandparents in the General Strike year of 1926. When The Happy Lands was shown in heavily industrialised mining areas in China and Australia it received a highly positive reaction from audiences who readily engaged with it. Corrie and Rae both reached out and found their constituency although Robert Rae still felt it necessary to use subtitles to convey Corrie’s rich Fife mining Scots.

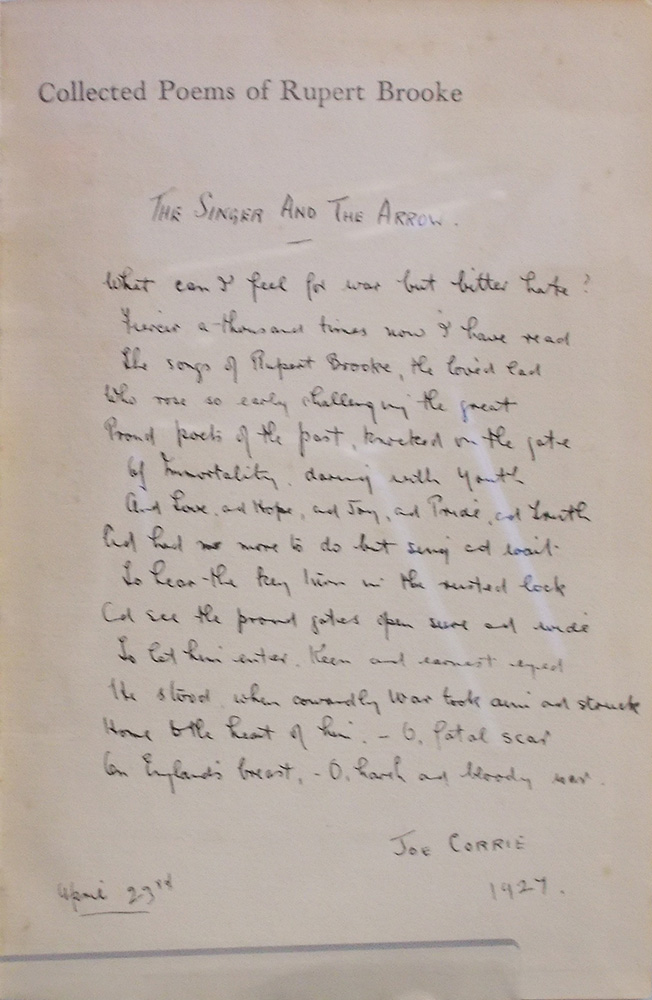

At the time the film The Happy Lands was being made I had contacted Joe Corrie’s surviving daughter Morag to ask her permission to revive The Bowhill Players, this time to record and perform a CD of her father’s poems and songs funded by Fife Council. Conscious of the SQA’s attempts to develop a Scottish Studies course for Secondary years 4-6 as part of The Curriculum For Excellence initiative, I offered to develop educational materials for a Theatre Workshop website based on Corrie and The Happy Lands film. In doing so I was aware of Corrie’s potential to draw people and communities together.

These educational resources were road tested at Beath High School, Cowdenbeath, just a few miles from Corrie’s Cardenden. I began by reading and discussing a core group of Corrie poems with a class. These included: The Image Of God, Cageload of Men, The Common Man, The Pedlar, The Gaffer, Tae A Pitheid Lass. Most of the poems were written in Scots. Initially, some pupils found the printed text of the poems difficult to understand and most needed some help with mining vocabulary. Some pupils found it difficult to understand the meaning of general Scots words although they often used these same words themselves in their normal speech. When I read the poems aloud to them the majority said that they had no difficulty in understanding the meaning of the poems. I have found this generally to be the case in teaching Scots language texts.

Having discussed and read the poems the pupils were asked to choose favourites, explain why they liked them and complete a short textual analysis assignment.

The group then watched the The Happy Lands film. In discussing the film, I tried to elicit how much the pupils knew about the former mining background of the Central Fife area from their personal/family experience. I was also interested to find out how much they had previously been taught about the political history of the mining communities in school. Were they aware for example, that martial law had been declared and that armed soldiers had been deployed in the High Street in 1921 against the community to suppress the miners’ demonstrations? The answer to both questions was that they knew surprisingly little (although it should be taken into account that the last pit in Cowdenbeath closed in 1963 and the community has had no major involvement with mining since the closure of the mining workshops in 1984). Pupils did express considerable sympathy for the treatment meted out to the mining community by the authorities as it is portrayed in the film. This was to be expected given the political stance of the film’s director, but it also allowed us to discuss the ways in which media techniques are used to manipulate audiences’ emotions and thoughts.

I then asked pupils if they could complete an assignment in which they interviewed an older relative such as a grandparent, uncle or aunt about their working lives and life experiences (not necessarily in coal mining). Pupils were required to formulate their own questions and having completed the interview, use the information to give a presentation to the group. This proved highly successful. Most of the interviewees did turn out to have a coal mining background and a number volunteered to come into school to take part in the presentations.

This approach gave pupils the opportunity to develop their research in further areas of the curriculum if constraints of time and timetabling allowed. The geology of coal could be studied in Geography; the history, culture and politics of the time in History and Modern Studies; a Corrie one act play such as The Darkness or The Shillin A Week Man could be attempted in Drama, while folk music and Corrie’s songs such as The Gaffer could be listened to and performed in Music.

Overall, this holistic approach was considered successful by both pupils and staff involved, with the pupils positive in their comments that they had learned much about their area and background that they hadn’t been given access to before. The learning process had been enjoyable while simultaneously meeting the requirements for literacy and learning outcomes for both Scottish Studies and English courses.

Joe Corrie’s work lends itself to schools in former coal mining areas but there is no reason that the same template cannot be applied to communities associated with either former or current industries and traditions through tapping into cultural sources and using these as a catalyst and starting point for wider study.

Engaging with the language of Joe Corrie’s poems allowed some pupils to become more aware of their own use of Scots language and even the extent to which they change registers from informal situations between friends and family and formal situations such as giving a presentation in school. To see students connecting not only on a generational level but a linguistic one was a positive experience from a teaching point of view. Traditionally, Scottish schools have been places where active discouragement of Scots language has been the norm. I believe that there must be a link between this and low self-esteem, lack of confidence caused by cultural poverty and accompanying low literacy skills in some children in central Scotland.

Sadly, much of the impetus behind this project was due to my own personal enthusiasm and when I retired from my post at Beath High School there was no one to continue with this. I believe the situation to be much the same across Scotland: Scots language and literature and culture in general is often taught by enthusiasts and individuals but not in a co-ordinated or in a systemised or mandatory way. So long as the SQA refuses to ensure the place of Scottish culture rather than leaving it to an arbitrary choice many children will leave school in the same state of ignorance as previous generations.

There have been confident predictions concerning the demise of the use of Scots since before the time of Burns yet in the Central Fife area a vibrant spoken Scots is still used by most of the community in shops, public places, sports clubs, youth organisations, churches. The vocabulary may have changed to reflect lifestyles but there is a retention of some mining words and expressions such as graith , puitten a shift in, lowsen time, being in a richt howk, etc. These terms are used in everyday conversation and transactions. At the same time, from personal observation, I believe that most speakers are comfortable with changing register whenever required to do so. Is this ability to adapt quickly to different linguistic contexts actually one of the factors that leads to the false notion that the Scots language is perenially dying out? Joe Corrie’s Scots, as he knew it, is alive and well and used commonly by old and young. If the language is still being used, then surely the work of the writer who used it so well as a medium to express the views of his community should still be promoted?

It would be wrong to assume that because there are no longer coal pits that there is no longer an audience for Joe Corrie. If we pose the question, is Corrie still a writer of social relevance? Then a plausible answer is – every bit as much as Neil Gunn, Edwin Muir, John Byrne, Violet Jacob or Ena Lamont Stewart.

To return to my introduction: Corrie himself may not have expected or even wanted his corpus of published work, (plays, poems, songs, short stories and two novels), to have been pored over and subjected to close analysis by academics. He had a deep conviction in the importance of a progressive and inclusive society that did not deny its citizens the opportuntity to better themselves and escape the fate of being little more than slaves within the capitalist system. For him, an educational legacy that promotes humanistic and social values surely would have been viewed both as a justification for his writing as well as a matter of some personal pride. Yet I believe that he would have been deeply disappointed by the lack of political progress fifty years on from his death where the educational and material gap between the richest and the poorest continues to widen rather than narrow. It is worth noting that the coal mining communities of Central Fife produced two outstanding aspirational role models during the early part of the twentieth century in Joe Corrie and the politician and Open University founder Jennie Lee. I would argue strongly that it is important that such role models are incorporated into our education system in Scotland as examples of excellence. I welcome this symposium today at St Andrews as a recognition of Joe Corrie’s legacy and as a positive step toward achieving this.