Joe Corrie’s papers, acquired by the National Library of Scotland between 1968 and 1986, comprise a total of 72 files (Acc.10839, Acc.10040, MSS.26490-26560). These include both published and unpublished typescripts of plays and poems, radio scripts, musical notations of songs, letters, diaries, notebooks, press cuttings, and pictures. Together with Corrie’s voluminous bibliography and numerous pieces published in The Miner (1923-1926) and Forward (1926-1950s), these files have vast and unexplored research potential.

Since the death of Morag Corrie, in 2017, copyright for these papers is now held by Mrs Meg Finnie, who kindly granted permission for the reproduction of Joe Corrie materials on the present website. Meg Finnie is the granddaughter of Joe Corrie’s long-standing friend and mentor, Andrew Hendry Doig (1880-1958). Born in Dundee and apprenticed as a coachbuilder, Doig went through several years of unemployment before finding work as a pit electrician, in Lochgelly. A few years later, when Corrie was hired down the mine, Doig took him under his wing and encouraged him in his writing. Like Corrie, Doig was a well-read man and a committed socialist, who believed passionately in the value of education and managed to send one of his sons to Edinburgh University. His support and friendship were later acknowledged by Corrie, who dedicated his 1919 notebook of handwritten poems to his mentor ‘in testimony of my admiration and joy which have derived during the course of many pleasant conversations’. Both friends kept in touch regularly after Corrie left Fife for Ayrshire in the late 1920s.

The following guide to Corrie’s archive offers descriptions, quotations, and pictures of key files and documents. Its aim is to encourage and facilitate future research on Joe Corrie.

MS. 26490-98. This first batch of 8 files contains the typescripts of 46 one-act plays, 43 of which remain unpublished. Amongst these is a dramatized version of George Douglas Brown’s The House with the Green Shutters (26492) as well as a play entitled ‘When Freedom Calls’, co-written by Corrie and St Valéry veteran, Ernest Reoch. MS. 26492 also contains a typescript of Corrie’s successful play, Hewers of Coal.

MS.26499-512. These files enclose the typescripts of fourteen longer plays, including two versions of In Time o’ Strife (the original one, in Scots (26504) and another version, in English, set in an English mining town (26504A)). Alongside these, are a dramatized version of Corrie’s novel Black Earth (26499), a typescript of Corrie’s successful play Master of men (26507), a typescript of Corrie’s 1940 banned play ‘Dawn’, renamed ‘Red Sky at Morning’ (26511) and two plays on Joan of Arc —‘The Saint in Armour’ and ‘The Maid of Domrémy’ (26511).

Typescript of In Time o’ Strife, NLS, MSS.26504,

reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

MS. 26513-520. This third batch of files comprises 21 plays adapted for broadcasting, including a version of Colour Bar (26517) and a dramatised rendition of Robert Burns’s ‘Tam o’ Shanter’ (26520).

MS.26521-25. These contain several of Corrie’s radio talks and unpublished prose, including his unpublished novel ‘Ploughman Murder’, (26521) and his 1937 radio series ‘Discovering Scotland’ (26522), as well as synopses of plots for films (26525).

MS. 26526-33. This section of Corrie’s papers encloses hundreds of poems, both in manuscript and typescript material. Of interest are MS. 26526-70, which contain typescripts of unpublished poems, arranged and listed by Corrie, and MS. 26533, which includes Corrie’s unpublished long poem from 1954, ‘The Mermaid’.

MS.26534-40. These six files comprise hundreds of songs, either collected or written by Joe Corrie, including a 160-page collection which Corrie arranged alphabetically by title in 1962-1963.

MS.26541-50. These are nine diaries, ranging from 1949 to 1958, concerning productions of Corrie’s plays, his travels, and finances.

MS.26551-552. These two files contain extracts of Corrie’s correspondence, from 1930 to 1967, as well as Corrie’s 1923 pedlar certificate, and miscellaneous papers and photographs. Amongst these, one letter is of particular interest and was sent to Joe Corrie by T.S. Eliot, on 9 March 1937, concerning the Porpoise Press edition of Corrie’s collection of poems, The Image o’ God‘. This letter was recently reprinted in Valerie Eliot, John Haffenden (eds.), The Letters of T.S. Eliot, Vol.8, 1936-1938, (London, 2019), p.527

MSS.26553-60. These seven files are press cuttings, ranging from 1927 to 1959. They include Corrie’s own works, published in diverse newspapers (Forward mainly), as well as diverse reviews and articles about him. Amongst other interesting pieces is an article written by Sergeï Dinamov (Corrie’s Soviet translator), entitled ‘Joe Corrie —An Artist of Labouring England’, translated by Ruth Kennell and published in The Miner, on 2 August 1930 (26560). Here are a few extracts:

‘Joe Corrie is an artist of the working-class. When he writes of the English mines he writes at the same time about himself. When he treats of the workers he is treating of his own class, to whom he has been inseparably bound throughout his whole life as a miner, writer, dramatist, poet, and journalist.

“Saturday evening is a great evening for us who are poor”, he writes in one of his stories. He does not separate himself from his heroes; he and they are in one class. In all his work, Corrie stands in opposition to bourgeois art; in all his work Corrie draws upon the working-class as a special object of poetry.

Corrie is resolute in these convictions. He does not conceal the fact that these miners are rough, dirty, ragged and is unsparing in vigorous expressions describing them. Corrie is ready even to emphasise these negative characteristics, fully understanding that they are caused by the conditions of the worker in capitalist society.

[…] Corrie is an artist of the little genre; he writes either short stories or short poems and plays. The working-class, even in the Soviet Union, has not created a single artist like him for treating life in the form of one ideology. The short stories of Corrie have for us an historical significance, because together with the works of R. Fox, Harold Heslop, James Welsh. M.P., Roger Dataller, and the stories of Stacey Hyde, they form a basis for proletarian literature in England.

In conclusion, it is necessary to add that Corrie is not only an artist of the working-class, but also an organiser of its culture, through his plays and the many groups of worker players, who are now playing them in his native Scotland’.

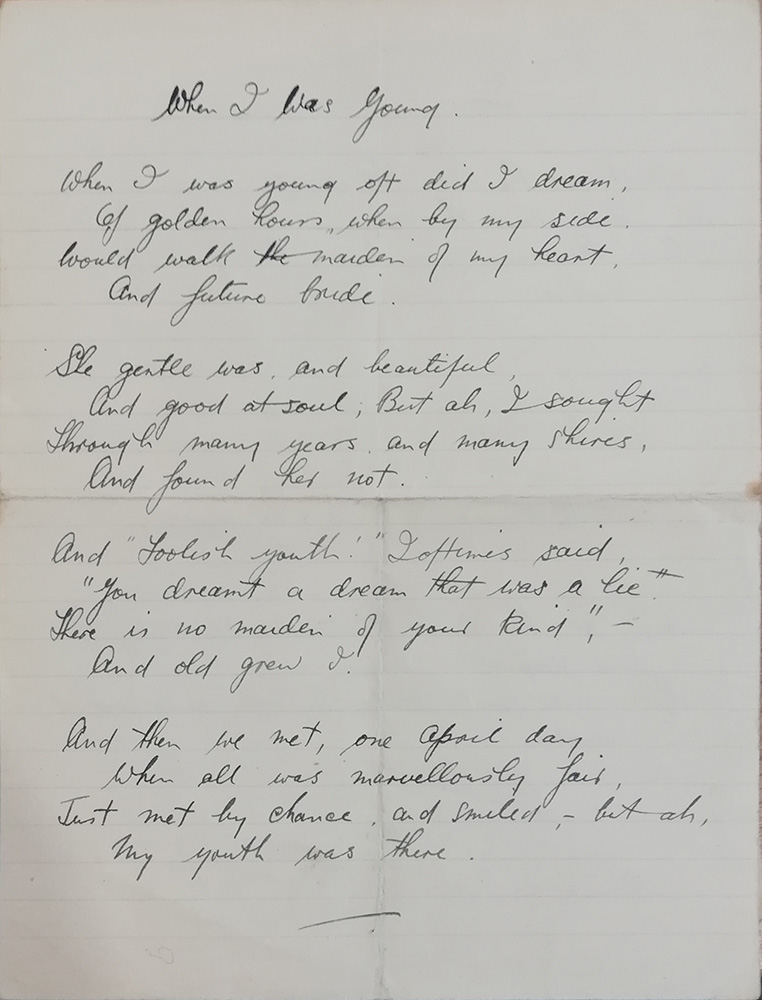

Acc.10040. This small file contains about 40 manuscripts and typescripts of unpublished poems. Here is one of them, an undated love poem, ‘When I Was Young’:

When I was young oft did I dream,

Of golden hours, when by my side,

Would walk the maiden of my heart,

And future bride.She gentle was, and beautiful,

And good at soul; But ah, I sought,

Through many years, and many shires,

And found her not.And “foolish youth”, I ofttimes said,

“You dreamt a dream that was a lie.”

“There is no maiden of your kind”, —

And old grew I.And then we met, one April day.

When all was marvellous and fair,

Just met by chance, and smiled —but ah,

My youth was there.

Manuscript of ‘When I was Young’, Acc.10040,

reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland

Acc. 10839. This file was deposited in the NLS by Morag Corrie, in 1986. It contains miscellaneous manuscripts and typescripts of early poems and songs, three letters to Andrew Doig, as well as miscellaneous photographs and Corrie’s first notebook of poetry. The latter is a striking piece of 20 poems, which reveal Corrie’s early themes and emotions as a young, working-class writer. Here are a few extracts:

Scotia’s Boast

When Januar’s winds blaw cauld and hard,

And folk are prone to grumph and swear,

Just think of Rab, Auld Scotia’s bard,

First welcomed by the frosty air.We hear a lot ‘bout Presidents,

And statesmen, great, or King and Queen,

Yet it takes wordy monuments,

To keep their memories evergreen.Such signs of greatness Time will fade,

And wintry gales and storms will rend;

But Rab, your monument was made

When in a book your muse was penned,So brither Scots, whaur’ere you be,

At hame or far across the sea,

Lift up your glass and drink the toast,

To Rabbie Burns, Auld Scotia’s Boast.

‘Scotia’s Boast’ in Corrie’s first notebook of poetry, 1919, Acc.10839, reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Fragment 5

Melancholia’s cursed

stang now draws my

tortured limbs alang,

I know not where

all I seek is some relief

from this imaginary grief,

Alas, I fear

Why must my heart with

grief be torn, why must

my hopes all seem forlorn,

Is it my destiny?

Then Death, if thou

would’st be a blessing

Release me from this

world, distressing,

Give me Liberty

‘Fragment 5’, in in Corrie’s first notebook of poetry, 1919, Acc.10839, reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.