In this dispatch from the field, Yannick Lengkeek discusses how his observations of people playing games during the COVID-19 lockdown in Portugal sparked a new trajectory in his research and led him to reconsider the role of ‘play’ during the Portuguese dictatorship.

Just before the pandemic ushered in this period of lockdowns and an incessant stream of regulations and restrictions on public life, travel, and freedom of movement, I was looking forward to a promising spring and summer spent unearthing new material all over Portugal. I had plans to use the temperate months of spring to explore the South of Portugal and Alentejo – a region with a reputation for summer temperatures beyond 40 degrees Celsius – and dedicate myself to the cooler North of Portugal during the hottest months of the year. The pandemic, however, completely derailed my plans.

Then again, I dare say that the pandemic ruined the plans of many, at least for the foreseeable future. Moreover, working in a fully funded project made me painfully aware of my privilege. I could feel it all over Lisbon. The social climate turned increasingly hostile, long before the wearing of masks became compulsory. Aggressive behaviour became more frequent in the streets, and the homeless started gathering in front of supermarkets around the neighbourhoods in ever greater numbers. It was all too obvious that the disappearance of civil society from the streets had a massive effect on the lives of the poorest of the poor, especially those who rely on begging as their primary means of survival.

Since beggars and the poor – among other marginalized groups – were originally a focus of my dissertation, I thought a lot about them and their experiences during the crisis. Under the dictatorship of Salazar, the authorities actively tried to confine beggars to specific spaces and keep them under control. From the regime’s perspective, homelessness was a stain on the immaculate social fabric of Portuguese society, since ‘home’ was the embodiment of Portuguese family values. During the lockdown, the bias that citizenship is tied to a home – which, needless to say, is anything but an exclusively ‘Portuguese’ notion – expressed itself differently, but the bias was the same. Stay at home is a message that only applies to those who can call a place with a roof and a front door their own – rented, bought, or otherwise. For all those who were unfortunate enough to be homeless, this message was pointless, apart from the fact that it once again highlighted the socioeconomic divides that run through society.

As for me, observing the behaviour of people in my immediate surroundings became one of my main coping strategies. While I always liked to think of my work as a form of historical anthropology, I suddenly found myself turning into a contemporary anthropologist, as I was analysing and deconstructing the practices and behavioural strategies of those around me. And to me, one thing stood out in particular: more than ever before, people of all age groups were turning to games and gaming as a survival strategy. At first glance, this seems hardly surprising: under situations of stress, people resort to various coping mechanisms, some deemed more ‘useful’, ‘responsible’ or ‘appropriate’ than others. The line between allegedly acceptable forms of coping, such as exercise and social drinking on the one hand, and supposedly destructive practices like drug abuse or gambling on the other hand, is not as clear-cut as it seems. Still, based on medical and psychological evidence, we may establish blurry lines between constructive and destructive coping mechanisms. The moral dimension of such coping strategies, however, is a whole new topic altogether.

Crisis and play

The phenomenon of play, an activity as old as humanity itself, is a particularly illustrative example for the abovementioned clash of priorities and values. While the role of play for the healthy development of children has become widely accepted conventional wisdom, the idea of adults engaged in playful activities comes with a great deal of stigmas and unspoken assumptions about the ‘adult mind’. Regulating socially acceptable forms of play, such as sports and family board games, and penalizing the pursuit of other forms of play is still widely perceived as the responsibility of the state and society as a whole.

The basic idea – both in the time period I am studying and in the present day – seems to be that adults indulging in unregulated games are succumbing to some primordial instinct. Adult play is, therefore, often still perceived as a behavioural atavism. However, two of the most important theorists of play who explored the role of play in culture and society both agreed on one thing: play is an inherently human trait, which, even though undeniably linked to our animal origins, never vanishes from the human mind. In every social or cultural artifact, we will find traces of play at work. As Johan Huizinga put it in Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture:

When speaking of the play-element in culture we do not mean that among the various activities of civilized life an important place is reserved for play, nor do we mean that civilization has arisen out of play by some evolutionary process, in the sense that something which was originally play passed into something which was no longer play and could henceforth be called culture. The view we take in the following pages is that culture arises in the form of play, that it is played from the very beginning. (HUIZINGA, 1944: 46)

Another brilliant scholar, Brian-Sutton Smith, who devoted his entire academic career to the study of play in all its forms and across all material and cultural platforms, shared Huinzinga’s evolutionist view of play as a survival mechanism. However, contrary to Huizinga’s much older theory of play, Sutton-Smith’s theory, which was shaped by his background in education, has a different focus, even though many basic assumptions are similar. While Huinzinga looked for the power of play as it manifests itself in culture at large, Sutton-Smith promoted a more ‘grassroots’ approach that is uniquely suited to the everyday life approach we adopt in our Everyday Dictatorship project. To sum it up in the original words of Brian Sutton-Smith:

Put more simply, play as we know it is primarily a fortification against the disabilities of life. It transcends life’s distresses and boredoms and, in general, allows the individual or the group to substitute their own enjoyable, fun-filled, theatrics for other representations of reality in a tacit attempt to feel that life is worth living. […] In many cases as well, play lets us exercise physical or mental or social adaptations that translate— directly or indirectly—into ordinary life adjustments. (SUTTON-SMITH 2008: 118)

In Lisbon, I observed the power of play around me. Young students who lived in the same house as me and were usually extremely attached to their smartphones suddenly bought puzzles and board games. And outside, despite government warnings and a strong police presence, elderly Portuguese men did not let the state interfere with their card games. During my morning runs in the park I would see them reclaim the benches and tables that had been sealed and marked by the police as ‘out of use.’ One may blame blissful ignorance, but based on my personal experience, I suspect that a great number of these men were aware of the health risks and, nevertheless, prioritised their social card games in the park. Speaking of parks, it is also worth mentioning that I saw an unprecedented number of adults play games in groups just small enough to avoid being fined. The police often intervened, disbanding groups and sending children and their parents’ home. It is not up to me to judge the interventions of the state in this particular situation. However, as a historian of everyday life, my observations revolve primarily around the experiences of people and individuals, which is why I simply had to look for comparisons with the Portuguese dictatorship. My main incentive was obviously not to pass judgement on extreme police measures and restrictions in the present day, but rather to get a better understanding of play as a coping mechanism under a repressive social climate.

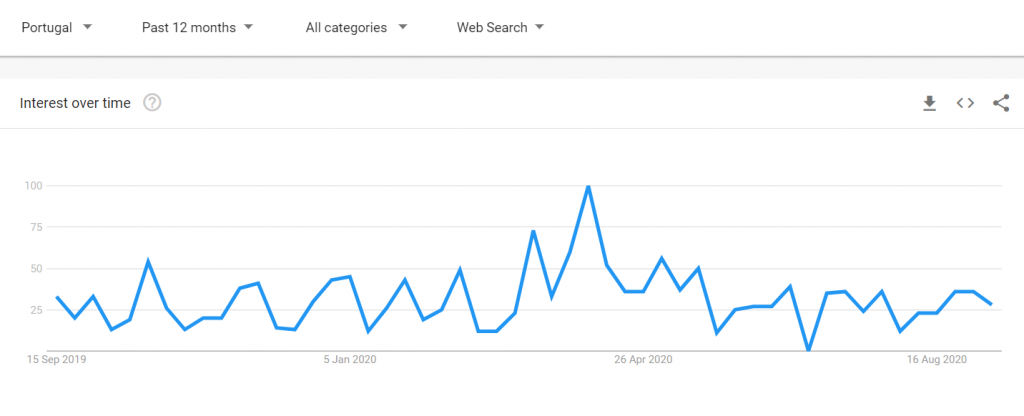

Since my research started out as an exploration of illicit activities and marginalised groups, gambling had already become one of my main subjects of interest before the pandemic started. My interest in this topic was additionally fuelled by learning that, despite dire economic prospects and mass unemployment on a global scale, online gambling, particularly in the form of poker, seemed to have experienced a marked boom in popularity across the globe. After reading on news platforms how online gambling revenues in the USA had spiked dramatically during the lockdown, I decided to run my own experiment and entered the keyword online poker in Google Trends, restricting my search to Portugal:

It seems, therefore, idealistic to say that people tighten their budget when circumstances become more dire. Instead, one gets the impression that it is precisely during such times that human beings crave the thrill, comfort, or joy of a game. Of course, gambling is a very particular form of play, but it is widely acknowledged to be one of the oldest forms of play, appealing to our deep-seated desire to put our lives in the hands of fate. At the same time, the allure of gambling is also linked to the illusion of control it provides the player with, the latter being a central characteristic of games in general.

Apart from individual hopes and desires, the cultural history of gambling also reveals how human societies have historically used contests involving a combination of luck and skill (games like poker or sports betting are contemporary examples) to settle conflicts and negotiate their social status without need for violence. In his famous essay ‘Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight,’ well-known American anthropologist Clifford Geertz describes the social role of cockfights in traditional Balinese communities. Following the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s notion of ‘deep play’ as a game with irrationally high stakes, Geertz set out to explain how, for many Balinese men, the assertion of status and masculine power fully justified the prospect of potential economic ruin. Therefore, to understand gambling in any society, we have to understand it within a very specific cultural context. What was the cultural background of gambling in Portugal under the Portuguese Estado Novo, and why is it worthy of closer scrutiny?

Historical perspectives on games and gambling in Portugal

According to my research, we ought to distinguish two forms of gambling not only because they operate in slightly different ways, but also because Portuguese society invested them with quite opposite moral qualities. I am speaking of the styles of gambling practiced in casinos or bars on the one hand, and lotteries on the other. The first lotteries were authorised in the late eighteenth century under the rule of Queen Maria I of Portugal. It was only in the late nineteenth century that a single institution, the Santa Casa da Misericordia, was granted a monopoly on the sale of lottery tickets in Portugal. Unlike lotteries in other parts of the world that were quickly exploited by emerging nation states as a means to raise taxes and make money (very similar to casinos), the Portuguese national lottery derived an exceptional moral authority from its historical link to the Santa Casa, a formerly ecclesiastic institution tasked with organising poor relief. In fact, it was exactly this particular moral authority that legitimised the monopoly, and it was only in 1955, under Salazar’s dictatorship, that the Santa Casa’s de facto monopoly was enshrined in law.

Throughout my research on everyday life under the Estado Novo, I realised that the lottery and the state were intertwined in many ways, and that, for a long time, buying lottery tickets in Portugal was widely considered an act of altruism and not a form of gambling. In public life, the Santa Casa was a revered institution, and apart from organizing lotteries, the institution also organised and hosted bullfights on properties owned by the Santa Casa da Misericordia. Casinos, on the other hand, operated in a moral grey area that the dictatorship could not publicly endorse, despite the fact that the Estado Novo raised respectable amounts of taxes every year thanks to the renowned casinos in the coastal towns of Estoril, Figueira da Foz, and Póvoa de Varzim. These three institutions attracted not only Portuguese high society, but also crowds of wealthy visitors from the rest of Europe and beyond. The Casino of Estoril, which was opened to the public in August 1931, was described by contemporary observers in the illustrated magazine Ilustração as ‘a sumptuous building, decorated with a good modern taste and an modern flair that is without precedent in Portugal.’ These days, the Casino do Estoril is more widely known as a likely source of inspiration for James Bond author Ian Fleming, who stayed in Estoril during the early 1940s while he was working as a spy for the British government. As for the casinos in Figueira da Foz and Póvoa de Varzim, they were undoubtedly not as modern, but no less symbols of a privileged hedonistic lifestyle.

The tension between ‘acceptable’ gambling and ‘inacceptable’ gambling is reflected in public discourse, legislations, and a constant attempt to keep citizens in line. For obvious reasons, the Estado Novo’s propagandistic depictions of Portuguese people as hardworking, diligent and family-oriented clashed with the idea of Portuguese men and women being gamblers and thrill-seekers. However, the regime did very little to actively fight gambling, as the considerable tax revenue was simply too tempting. This temptation is hardly unique to Salazar’s Portugal. It is, however, remarkable to see how the regime blurred the line between ‘illegal’ and ‘immoral’ whenever people met to gamble on their own, without providing any economic benefits to the Portuguese state. For instance, multiple police reports I found from the Porto area depict gambling among friends or colleagues in bars or cafés as an immoral act. It is a trademark of dictatorships to actively conflate law and morality, turning a private session of card games into an act of resistance against the state, even though these acts were likely not intended as attacks against the state, but simply as a form of sociability and play.

At the same time, cultural and state-supported institutions like the Casas do Povo (‘People’s houses’) installed by the regime and older institutions, such as the Sociedade Harmonia Eborense in the city of Évora (to name just one example with an excellent archival record) worked to provide and control ludic activities, including card games, backgammon, and billiards. While these institutions provided games, a space and a community feel, they also exercised control over ludic activities. In that sense, unfettered gaming and gambling remained a privilege of the wealthy few, while the average citizen either risked playing ‘illegally’ (and arousing suspicions) or playing in a space provided by the state or cultural institutions that relied on state support. Hence, those who could not afford access to the more glamorous casino scene were left with limited options, and any form of play involving chance or risks outside of these privileged spaces was branded as ‘immoral.’ The only moral alternative for a gambler with limited financial resources, irrespective of gender and social status, was the lottery.

Rethinking categories

As my work keeps evolving, I am also thinking more and more about the evolution of games and how some of them, such as billiards, slowly became accepted as sports. The Sociedade Harmonia Eborense, for example, hosted a whole series of billiards tournaments. And while billiards is not a form of gambling, as it is based entirely on skill, it emerged from a similar cultural milieu that is not very different from poker, blackjack or roulette.

Exploring different forms of (adult) play also forces me to think more about the regime’s relationship with sports (some of which, like football, are thoroughly researched) and children’s play, including the educational aspect of play. My focus is clearly on adult play and the tensions it creates between moral expectations, ideals of productivity and a deep-seated human need for downtime, connection, and distraction. I am particularly interested to see how questions of good conduct, autonomy and leisure were constantly negotiated under the ever-watchful eye of the regime. Within this framework, play appears as a very distinct form of human agency, through which citizens sought to establish communities, negotiate social status and regain a sense of control over their lives – even if, as in the case of gambling, it is more of an illusion of control.

The chaos caused by the pandemic shifted my attention to forms of coping that transcend class, age groups, gender, ethnicity, and religion. Looking at play as a prism through which I can explore agency, power dynamics, values, and contested notions of good citizenship, I am confident that this new path will result in a dissertation that approaches the question of how citizens navigated their everyday lives in times of limited freedom from a fresh perspective. In my upcoming posts, I will share bits and pieces of my research and elaborate on specific problems pertaining to play, including photographic materials and leaflets to show the power of play in all its colours.