- Navigation:

- Back to the Corpus index page

- RSS

St Andrews St Leonard Parish Church

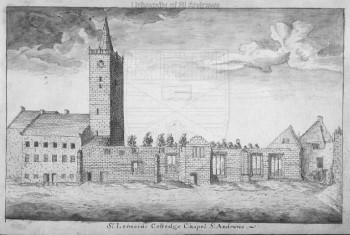

St Andrews, St Leonard, (John Oliphant, 1767)

- Dedication: St Leonard

- Diocese of St Andrews

- Deanery of Fife

- NO 51272 16602

Summary description

The rectangular chapel of a college founded in 1512-13 on the site of a hospital of 1144; a tower was inserted at the west end, possibly around 1544, and the chapel was also extended eastwards. Abandoned for parochial worship in 1761, after which the tower was demolished and the roof removed, and in about 1853 the western bays were demolished. Re-roofed and re-glazed 1910; restored for worship 1948-52.

Historical outline

Dedication: St Leonard

The origins of the later medieval parish of St Leonards lie in the chapel of the hospital associated with the monastery of St Andrews. This hospital, with no reference to its specific dedication, was granted to the Augustinian priory at St Andrews by Bishop Robert, apparently in 1144, although the charter recording the grant is probably a confection in its surviving form.(1) The ‘new hospital’ was mentioned in a charter of Bishop Arnold (1160-1162) and as the Hospital of St Leonard was confirmed to the priory in a general bull of Pope Innocent IV in 1248.(2) Pope Innocent’s bull included all of the lands, principally the grange of ‘Kellakin’, and all pertinents, teinds and houses attached to the hospital.

St Leonards has no independent parochial existence until the early fifteenth century. It occurs first as a parish church in 1413, when it served as the meeting place for an ecclesiastical tribunal.(3) What relationship it had with the church and parish of the Holy Trinity, St Andrews, within whose territory it was wholly encompassed, is nowhere made explicit. It is likely, however, that its parochial status was limited solely to the properties attached to it and was perhaps primarily an artifice to permit all gifts made to its altar to be diverted fully into the hands of the canons, who continued to enjoy the teinds of the hospital and its lands into the 1500s.

On 20 August 1512, Alexander Stewart, archbishop of St Andrews, and John Hepburn, prior of St Andrews, jointly founded the college of St Leonard in the University of St Andrews, erecting the hospital and church of St Leonard into the ‘college of poor clerks’.(4) The hospital’s teinds thereafter became the principal basis of the endowment of the college’s master, its four chaplains, and twenty-six scholars of its original constitution, later altered to a principal, two priests, four regents and a variable number of students. Evidence for the continuing parochial function of the church after 1512 is slender, but in 1550 one John Fleming registered his testament with the commissary court of St Andrews, one of his testament’s terms being that he would be buried within the parish church of St Leonards.(5) One of the witnesses to the deed was John Fyfe, who was described as curate of St Leonards.

In 1561the kirk session of St Andrews instructed the parishioners of St Leonards to worship only in the burgh kirk of the Holy Trinity. (6) This formal instruction appears to have marked the end of the independent parochial status of the church, although the college continued as an educational institution supported on its original endowment. There is no record of the church in the Thirds of Benefices. It was, however, noted in the St Andrews kirk session records in 1592 that a child had been baptised in the church of St Leonard.(7)

Notes

1. Liber Cartarum Prioratus Sancti Andree in Scotia (Bannatyne Club, 1841), 123 [hereafter St Andrews Liber].

2. St Andrews Liber, 103, 127.

4. I B Cowan and D E Easson, Medieval Religious Houses: Scotland, 2nd edition (London, 1976), 233.

5. NRS St Andrews, Register of Testaments, 1 Aug 1549-12 Dec 1551, CC20/4/1, fol. 275-76.

6. Register of the Minister, Elders and Deacons of the Christian Congregation of St Andrews Kirk Session… 1559-1600, ed D Fleming (Scottish History Society, 1889-1890), 76.

Summary of relevant documentation

Medieval

Synopsis of Cowan’s Parishes: In origin a church of the hospital belonging to Culdees, the church was assigned to the priory of St Andrews in 1144. In 1413 it was recorded as a parish church, the teinds remaining with the priory, until it was erected into a college in 1512.(1)

1550 (12 Sept) John Fleming registered his testament with the commissary court of St Andrews, specifying burial in the parish church of St Leonard’s; it was witnessed by John Fyff, curate of the church.(2)

1561 (25 Apr) Kirk session of St Andrews orders that the parishioners of St Leonards should worship in the parish church of St Andrews (this measure not prejudicing the profits of St Leonard’s college).(3)

1592 (15 Apr) Church seems to be back in use when St Andrews kirk session records that Robert Wilkie baptised a child in the parish church of St Leonard’s.(4)

1598-1600 Some uncertainty as to the bounds of the parishes of St Leonard’s and St Andrews. Two cases in the St Andrews kirk session in which parishioners of St Andrews are arraigned for worshipping in St Leonard’s.(5)

Post-medieval

Books of assumption of thirds of benefices and Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices: [Church does not feature]

Statistical Account of Scotland (Rev Joseph McCormick): [No reference to church]

New Statistical Account of Scotland (Rev J Hunter, 1837):‘The original church of the parish was situated in the vicinity of the college… and for more than two centuries was occupied by the parishioners. About 70 years ago (c.1768) it required extensive repairs [decision made to make chapel of St Salvator’s the parish church instead]. The walls of the old parish church still remain in tolerable state of repair; but the tower and squire were pulled down soon after the transfer. Dimensions were 70 feet by 18 wide inside the walls’.(6)

Notes

1. Cowan, The parishes of medieval Scotland, 176.

2. NRS St Andrews, Register of Testaments, 1 Aug 1549-12 Dec 1551, CC20/4/1, fol. 275-76.

3. Register of St Andrews Kirk Session, 76.

4. Register of St Andrews Kirk Session, 728.

5. Register of St Andrews Kirk Session, 853 & 933-34.

6. New Statistical Account of Scotland, (1837), ix, 502.

Bibliography

NRS St Andrews, Register of Testaments, 1 Aug 1549-12 Dec 1551, CC20/4/1.

Cowan, I.B., 1967, The parishes of medieval Scotland, (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh.

New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45, Edinburgh and London.

Register of the Minister, Elders and Deacons of the Christian Congregation of St Andrews Kirk Session… 1559-1600, 1889-90, ed. D. Fleming (Scottish History Society), Edinburgh.

Architectural description

The chapel of St Leonard has been altered on so many occasions, both in the course of the middle ages and since the Reformation, that there is a great deal of uncertainty about the inter-relationships and dating of its constituent elements, and parts of what is said in this description may require revision in the light of further research. As it presently stands, it is an accurately oriented rectangular structure of 26.05 by 7.75 metres, with a rectangular sacristy of 8.6 by 3.75 metres projecting off the east end of its north wall. However, it is thought to have had an eventual medieval length of over 30 metres, with a tall tower rising from within the now demolished western part, and a two-storeyed porch projecting from its south flank. On the north side is an eighteenth century rustic grotto with a roughly finished wall head, a pointed-arch doorway in the north wall and a window in the east wall; it is covered with a shell-encrusted vault.

It is possible that the core of the building incorporates some of the fabric of the Culdee hospital chapel of St Leonard as it was rebuilt following its grant to the Augustinian Canons of the cathedral by Bishop Robert in 1144,(1) or of the church that had come to be regarded as parochial by 1413.(2) However, although the north wall certainly incorporates large amounts of cubical masonry, during the restoration of 1948-52 it was deemed that the foundations beneath that wall were ‘of late medieval character’, suggesting that any earlier masonry was in secondary use.(3) It therefore appears that the earliest identifiable features should almost certainly be associated with the college founded by Archbishop Alexander Stewart and Prior John Hepburn in 1512/13.(4)

The chapel as rebuilt for Stewart and Hepburn is thought to have had its east wall aligned with the easternmost buttress against the south wall, which has the arms of Prior Hepburn set into its upper part, and which is located about 8.5 metres from the present east wall. At this stage of its existence the chapel is thought to have had a length of around 22 metres, and to have abutted other college buildings at its west end. On this basis, the easternmost window of the building before it was extended eastwards was a rectangular three-light opening with cusped light heads, within reveals of cavetto profile to the jambs and a broad chamfer to the flat-arched head. West of this is a lintelled doorway with quirked roll-moulded reveals, that is known from the view of 1767 by Oliphant to have been covered by a two-storeyed porch that had a rectangular three-light window to its upper storey and a crow-stepped gable.

West of this doorway is a sequence of a rectangular two-light window with similar mouldings to the three-light window further east, but with no cusping to the light head; this is followed by a two-tiered arrangement with a small slit window at the lower level that has a buttress immediately to its west, and a larger upper window cutting into the eaves cornice. West of the buttress there are again two tiers of windows, with a rather compressed uncusped rectangular two-light lower window, and an upper window similar to that to its east. Oliphant’s view appears to suggest that there were two further upper windows in the demolished western part of the chapel, with two doorways at the lower level, though there was no vertical alignment between the upper windows and the doors.

The extent of the changes the chapel has undergone means that it is difficult to be certain how this pattern of windows and doors reflected the early sixteenth-century liturgical arrangements. But perhaps the most likely interpretation is that the three-light window with cusped light heads lit the presbytery area of the chapel, and that the uncusped two-light window lit the choir, with door between, which was once covered by a porch, serving as the entrance for the clergy. Support for the three-light window lighting the presbytery may be derived from the existence of an aumbry immediately to its east, a feature that indicates the proximity of an altar.

On this basis the two-tiered arrangement of windows to the west of the choir window could have related to the screen between choir and nave, with the lower slit window lighting one of the altars in front of the screen, and the upper window lighting the rood loft. However, the way in which the upper window cuts into the wall-head cornice, and the fact that it has reveal mouldings of ogee profile, suggest that its present form is the result of post-Reformation modifications, and this may also be the case for the upper windows further west, the one surviving example of which has more complex ogee-profiled reveals. At least some of these windows are likely to have dated from after 1578, when the chapel was adapted for reformed worship, changes that involved the construction of a west gallery for members of the college attending services in the nave.(5) Within the surviving part of the chapel there are also four windows at a high level along the north side of the nave, one of which is now blocked.

At some date prior to the Reformation the chapel was considerably augmented at both the east and west ends, The eastward extension increased the chapel’s length by about 8.5 metres, and a two-storeyed sacristy and treasury block was built on the north side of that extension. At the west end a tall tower was inserted in a way that seems most unlikely to have been part of any original intention, since it appears to have left awkwardly narrow corridor-like spaces down each of its flanks. Since the insertion of the tower within the western part of the nave would have significantly reduced the amount of the nave that was available for worship, it is likely that one of the reasons for the additions at the east end was to permit the presbytery and choir to be relocated eastwards, permitting the area that had initially been the choir to be absorbed into the nave. It is uncertain precisely where the division between choir and nave would have been located in this revised arrangement, though it may well be that it came to be associated with the door that it has been suggested was initially between the presbytery and choir, and this was the position that was selected for the restored screen in the restoration of 1948-52.

It seems that the limit to further eastward extension was the existence of the priory precinct wall, though it is far from clear how the chapel’s new east end related to that wall. The chapel’s east wall is in the form of a double skin of masonry enclosing two levels of corridors, the lower of which led off the sacristy, while it may be assumed that the upper corridor led off the now-demolished treasury above; from those corridors narrow windows looked into the chapel. There may also have been some communication with an offshoot at the south-east corner of the chapel, where there is the jamb of a window that was evidently part of a structure that projected southwards. Perhaps this was the dwelling of the senior chaplain who also served as the parish priest, who was required to occupy ‘the chamber next the outer gate, so that he may hear the parishioners calling for the administration of the sacraments’.(6) Oliphant’s view suggests there was a substantial building projecting at this point by 1767, though by that stage, like the chapel itself, it was roofless.

Along its south flank the new eastward extension was lit by an arrangement of windows that was evidently intended to repeat as closely as possible the fenestration that had been provided in the original presbytery and choir area: a rectangular three-light window to the east, with cusped light heads, and a rectangular two-light window with uncusped light heads to its west. The reveal mouldings of the earlier windows were also closely followed, and it is only the slight differences in the treatment of the easternmost window’s cusping that show the work is later. Internally a new aumbry was provided to the east of that easternmost window, and there are the relics of a piscina basin capped by a tabernacle head against the east jamb of the window. A higher level of architectural enrichment to the new presbytery area was provided by tabernacle work in the jambs of the easternmost window, and by an elegant doorway into the sacristy that has a filleted roll flanked by diagonally-set cavettos to the reveals, with a basket arch cut into the lintel. The date of this phase of work is unknown, though it is an attractive possibility is that it dates from the augmentation of the college for Cardinal David Beaton in 1544.(7) It may be noted that the mouldings of the sacristy door are very like those of a truncated door set in the blocking of the west tower arch of St Rule’s Church, within the cathedral precinct.

Within the sanctuary area, and now protected by a carpet, are a number of later medieval incised ledger slabs. The northernmost, which has a depiction of a priest in mass vestments, has an inscription thought to refer to the sacrist Thomas Fyffe.(8) The middle one has a depiction of an Augustinian Canon, and it has been suggested it may commemorate Alexander Young, the Principal of the college who died at a date between about 1544 and 1550. The southernmost is a heraldic slab for John Winram, sub-prior of the cathedral priory and prior of Loch Leven; he conveyed that priory to St Leonard’s before his death in 1582,(9) having become the Superintendent of Fife after the Reformation. In the south-west corner of the nave is a cross slab for Canon William Ruglyn, who died in 1502.

Following the Reformation St Leonard’s continued to function as a college, and in 1578 it was formally established as a parish church, with the interior opened up to make it more suitable for reformed worship. Presumably around the same time the gallery that has already been mentioned was constructed in the western part for members of the college. In 1727 the upper part of the tower was remodelled, with a spire set behind a balustrade parapet.(10) A number of imposing mural monuments of aedicular form were set up along the north wall of what had been the areas of the presbytery and choir in the post-Reformation period. The easternmost of these commemorates Robert Stewart, earl of Lennox and March, bishop-elect of Caithness, and commendator of St Andrews cathedral priory, who died in 1586. West of this is a damaged monument that is assumed to have been for Principal Peter Bruce, who died in 1630, and it has been restored as such. The westernmost monument is for Principal Robert Wilkie, who died in 1611.

As a result of the difficulties in which the university found itself, in 1747 it was decided that the colleges of St Leonard’s and St Salvator’s should be united and concentrated in the buildings of the latter, and in 1761 St Leonard’s chapel was also abandoned for parochial worship. The roof of the chapel was removed and the tower demolished. However, although the shell of the main body of the building was retained against the possibility of future restoration, it seems that at some stage a cross wall must have been raised on the line of the present west front.

Some reversal of the chapel’s fortunes may have begun in 1853, when Principal Sir David Brewster cleared out the rubbish and vegetation that had accumulated within its walls, and the windows were reopened, as is seen in the views in MacGibbon and Ross’s account of the chapel.(11) But Brewster also removed what remained of the western parts of the building to create a carriage drive to his house on the opposite side of the courtyard from the chapel, and he formed a barrel-vaulted wine cellar within the sacristy. It was presumably at this stage that the west front was given its present form, incorporating a variety of architectural fragments. These include two tablets with the arms of Prior Hepburn, one relating to Patrick Hepburn, the nephew of the Prior John Hepburn who founded the college. Several of the fragments are likely to have come from the cathedral rather than the college, including a number of crockets similar to those on capitals that have been found through excavation within the cathedral. The south-west corner of the chapel was curved to allow easier passage for the Principal’s carriage.

A more positive approach began to be taken in the twentieth century. In 1910 the chapel was re-roofed and re-glazed, with the intention that it might serve as a hall of fame for members and benefactors of the university. But it was only in 1948 that it was decided the chapel should be restored for worship, and work was undertaken to the designs of Ian Lindsay and Partners, being completed in 1952. As part of this operation a screen and organ loft were inserted on what was thought to have been its final medieval line, with stalls and a communion table set up within the choir area, and a pulpit within the otherwise unfurnished nave.

Notes

1. Liber Cartarum Prioratus Sancti Andree in Scotia, ed. Thomas Thomson, (Bannatyne Club), 1841, p. 123.

2. Liber Cartarum Prioratus Sancti Andree in Scotia, ed. Thomas Thomson, (Bannatyne Club), 1841, pp. 15-18.

3. Ronald Gordon Cant, St Leonard’s Chapel St Andrews, St Andrews, 3rd ed. 1970, p. 7.

4. J. Herkless and R.K. Hannay, The College of St Leonard, Edinburgh, 1907-15, pp. 130-5.

5. Ronald Gordon Cant, St Leonard’s Chapel St Andrews, St Andrews, 3rd ed. 1970, pp. 8-13.

6. Ronald Gordon Cant, St Leonard’s Chapel St Andrews, St Andrews, 3rd ed. 1970, p. 4.

7. J. Herkless and R.K. Hannay, The College of St Leonard, Edinburgh, 1907-15, p. 144.

8. J. Herkless and R.K. Hannay, The College of St Leonard, Edinburgh, 1907-15, p. 216-7.

9. D.E.R. Watt and N.F. Shead, The Heads of Religious Houses in Scotland from Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries (Scottish Record Society), 2001, pp. 141-2.

10. Ronald Gordon Cant, St Leonard’s Chapel St Andrews, St Andrews, 3rd ed. 1970, p. 13.

11. David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross, The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland, Edinburgh, vol. 3, 1897, fig. 1390.

Map

Images

Click on any thumbnail to open the image gallery and slideshow.

2. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, graves in sanctuary area, Master John Winram, d. 1582

3. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, graves in sanctuary area, Principal Alexander Young, d. 1544x50

4. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, graves in sanctuary area, Sacrist Thomas Fyffe, d. before 1550

9. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior, north wall, middle section

10. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior, north wall, west section

11. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior, south wall, nave windows

12. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior, south wall, upper window 1

13. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior, south wall, upper window, 2

14. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, monument to Robert Stewart, earl of March

16. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, choir south wall, window sill of east window

18. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, choir, south wall, piscina in east window east jamb

19. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, lower mural passage in east wall

20. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, monument to Principal Peter Bruce

21. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, monument to Principal Robert Wilkie

25. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, south wall, east jamb of east window

26. St Andrews, St Leonard, interior, south wall, later aumbry

31. St Andrews, St Leonard's, in its ruined state (MacGibbon and Ross)

39. St Andrews, St Leonard, exterior Hepburn arms on buttress

40. St Andrews St Leonard, Lower internal window from east passage

42. St Andrews St Leonard, east end, John Oliphant, 1767 (detail)