- Navigation:

- Back to the Corpus index page

- RSS

Liberton Parish Church

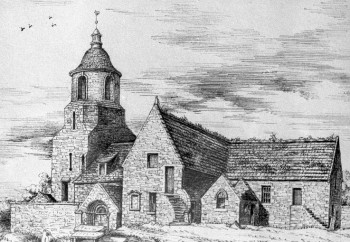

Liberton Church, exterior, before reconstruction (Andrew Kerr)

- Dedication: Our Lady

- Diocese of St Andrews

- Deanery of Linlithgow

- NT 275 694

Summary description

Probably a cruciform building with a west tower and south porch by the Reformation, to which further aisles were later added. Replaced by a new building on or near the same site in 1815.

Historical outline

Liberton first occurs on record between 1128 and 1147 when it was granted by Mael Beatha, lord of Liberton and Leadburn, as a dependent chapel of St Cuthbert’s, Edinburgh, with its mother-church to the canons of Holyrood.(2) It was confirmed in the abbey’s possession by King David I in his great charter which consolidated all of the disparate properties and rights which had been granted to Holyrood since its foundation, and also by Bishop Robert Robert of St Andrews.(3) Possession was further confirmed 1165x1172 by Geoffrey de Melville, lord of Liberton.(4) As a dependency of St Cuthbert’s, all of its revenues flowed to the abbey, to which the parsonage of St Cuthbert’s had been appropriated and Holyrood’s benefit was further enhanced by the vicarage settlement of 1251 which permitted the abbey to serve the cure with one of their own brethren (5)

At some unknown point after 1275 Holyrood appears to have secured independent parochial status for Liberton, for the church does not appear in the papal tax-collector’s rolls in that year. The parsonage was presumably annexed immediately to the abbey and a vicarage established to serve the cure. Hard evidence for this, however, does not appear to survive before 26 October 1536 when a complaint concerning an unspecified offence was brought by the parishioners and the master of the fabric of Liberton against their curate or vicar pensioner Adam Sanderson, which resulted in his suspension and excommunication.(6) The implication from Sanderson’s title is that both parsonage and vicarage revenues were annexed to the abbey and a pensionary vicarage rather than vicarage perpetual had been established by that date. Confirmation of the annexation of the parsonage is provided by the record in 1539 of the abbey’s set of the garbal teinds to Hugh and Martin Carberry.(7) This arrangement was confirmed at the Reformation when both parsonage and vicarage were recorded as being held by Holyrood, the former being set for £45 16s 4d annually and the latter for £28 13s 4d.(8)

It is known from 1507 that the main dedication of the church was to the Blessed Virgin Mary but a secondary altar and chaplainry was established in Liberton at the end of the previous century. On 15 February 1499 John Heriot in Stonehouse granted a charter to the parish church and a perpetual chaplain at the altar of John the Baptist there, giving an annual rent of 10 merks from his lands of Stonehouse in the barony of Melville. The gift was made especially to Sir David Heriot, his cousin, whom he ‘elected’ to the chaplainry.(9) In 1507 a certain Adam Bell gave an additional gift of 26s 8d annually to the chaplain of St John the Baptist in the church of St Mary of Liberton.(10)

Notes

1. Protocol Book of John Foular, 1503-1513, ed W McLeod (Scottish Record Society, 1940), nos 315, 703.

2. The Charters of David I, ed G W S Barrow (Woodbridge, 1999), no.147.

3. Liber Cartarum Sancte Crucis (Bannatyne Club, 1840), nos1, 2 [hereafter Holyrood Liber].

4. Holyrood Liber, appendix ii, no.2.

6. Liber Officialis Sancti Andree (Abbotsford Club, 1845), 136.

7. Holyrood Liber, appendix ii, no.35.

8. J Kirk (ed), The Books of Assumption of the Thirds of Benefices (Oxford, 1995), 91, 93, 107.

9. NRS Papers of Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, GD103/2/45.

Summary of relevant documentation

Medieval

Synopsis of Cowan’s Parishes: A chapel of St Cuthbert’s, Edinburgh, it passed with the mother church to Holyrood in 1128. It had achieved parochial status before the Reformation when its parsonage revenues remained with the abbey. The cure was a vicarage perpetual, probably served by a canon.(1)

Mackinlay notes that the church ‘is believed to have been dedicated to the Virgin Mary’.(2)

1128x47 Chapel of Liberton given to the abbey by Mael Beatha, lord of Liberton and Leadburn, with two oxgangs and 6 acres of land.(3)

1165x72 Geoffrey de Melville (lord of Liberton from 1153x65) confirms earlier grant.(4)

1536 (26 Oct) Complaint by the parishioners and the master of the fabric of Liberton against their curate or vicar pensioner Adam Sanderson (suit mentions both titles). Suit is successful and Adam is suspended and excommunicated [not clear what he did to deserve this, only the sentence is extant].(5)

1539 Garbal teinds of rectory of Liberton set to Hugh and Martin de Carberey.(6)

Altars and chaplaincies

St John the Baptist

1499 (15 Feb) Charter by John Heriot, in Stonehouse, to the parish church of Libbertoun and a perpetual chaplain at the altar of John the Baptist, and especially to Sir David Heriot, his cousin, whom he elects to celebrate, of an annualrent of 10 merks furth of the lands of Stonehouse in the barony of Mailwile, in the sheriffdom of Edinburgh.(7)

1507 Adam Bell gives 26s 8d to the chaplain of the altar of John B in in the church of St Mary, Liberton.(8)

Post-medieval

Books of assumption of thirds of benefices and Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices: The Parish church parsonage with Holyrood, set for £45 16s 4d. Vicarage set for £28 13s 4d.(9)

Account of Collectors of Thirds of Benefices (G. Donaldson): Third of £9 11s 1 1/3d.(10)

1567 Adam Bothwell, bishop of Orkney (and commendator of Holyrood) hauled in front of the General Assembly accused of allowing parish churches to decay. He answered that he had repaired St Cuthbert’s and Liberton churches which had been in poor repair.(11)

1595 (3 Mar) Two men called to compear infront of the Presbytery of Edinburgh anent the breaking of the floor of the church of Liberton notwithstanding the prohibition by the council of session (the kirk session told to remove the dead body from the church).(12)

1596 (15 June) Further reference to burial in Liberton kirk in front of the Presbytery of Edinburgh, John Henderson of Farnell compeared and accused of burying his child in the church (child was later removed and buried in the church yard).(13)

1598 (25 July) Visitation of the church by the Presbytery of Edinburgh finds the minister (James Bennet) to be competent, the fabric of the kirk is being ruinous and not water tight and the kirk yard dykes are to be repaired before the next session.(14)

1599 (28 Aug) Visitation of the church by the Presbytery of Edinburgh finds that the people regret that James Bennet does not reside in Liberton. Having admonished the people for the slate ceiling of the kirk, they promise to amend the same, the kirk dykes are down, the parishioners promise to build them again.(15)

[Noted that steeple needs major repair, takes some time]

1642 (13 Apr) Visitation of the presbytery takes into consideration the need to mend the office house and the steeple.(16)

1643 (14 May) John Scott to be approached anent work on the church steeple; on 4 June a notice was posted of a stent that is to be drawn up for the repair of the steeple.(17)

1645 (Aug) 50 dollars paid to the masons working on the steeple (heritors to pay later).(18)

1646 (6 July) Session orders certain elders to take care for ordering the stones from the quarry for the steeple.(19)

1646 (26 July) The minister, elders and heritors meeting with wrights have found the steeple of the church to be altogether ruinous and decayed, to be repaired the new roof to be built and thicket with slate, costs to be established and then a stent organised.(20)

1652 (29 Aug) Noted that a stent is to be organised for mending the minister’s house, kirk and kirk yard dykes.(21)

1659 (6 Feb) That day a letter from General Monk was read to the session granting funds for repairs for the kirk, kirk yard dykes and minister’s manse.(22)

[New bell ordered from Flanders]

1670 (30 Oct) The heritors convened a meeting with the elders which notes the necessity and expedience of having a new bell. A proportional stent to be organised. Men appointed who have acquaintance with the merchants of Edinburgh who have connections with Holland (noted that the old bell was to be traded in).(23)

1670 (9 Nov) Report made anent the new bell, the merchants trading with Holland did vary in account they gave about the new bell. The old bell to be taken down and taken to Leith.(24)

1671 (6 Aug) The session notes that the new bell was brought from Holland consisting of 850 pound weight and was satisfactorily hung in the steeple (noted that 550 marks was paid and 300 was received for the old bell).(25)

1683 (19 Aug) Noted in kirk session that an agreement had been made with a slater for the maintenance of the church roof and windows yearly at a cost of 10 marks. In another note of the same on 24 Aug it was mentioned that the slater/glasier would maintain the church and aisles which had slate roofs.(26)

1683 (2 Sept) A meeting of the session and the heritors notes that Lord Ross’ aisle on the south side of the church stood in need of reparation. A further stent to be ordered for repairing the aisle, although it is judged that in law my lord himself ought to mend it at his own expense.(27)

Statistical Account of Scotland (1791): ‘In this village [Over Liberton] is the church, an ancient building’.(28)

New Statistical Account of Scotland (Rev James Begg, 1839): ‘The parish church was erected in 1815’.(29) [no reference to former building]

Notes

1. Cowan, The parishes of medieval Scotland, 132.

2. Mackinlay, Scriptural Dedications, Edinburgh, p. 90.

3. Charters of David I, no. 147.

4. Holyrood Liber, no. App ii, no. 2

5. Liber Officialis Sancti Andree, p. 136.

6. Holyrood Liber, no. App ii, no. 35.

7. NRS Papers of Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, GD103/2/45.

8. Prot Bk of John Foular, 1503-1513, nos. 315 & 703.

9. Kirk, The books of assumption of the thirds of benefice, 91, 93 & 107.

10. Donaldson, Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices, 27.

11. Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, i, pp. 162-63 & 167-68.

12. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol. 99.

13. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol. 172.

14. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol., fols. 240-241.

15. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol. 299.

16. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 37.

17. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 43.

18. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 57.

19. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 60.

20. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 61.

21. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 95.

22. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 119.

23. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 167.

24. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 169.

25. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1, fol. 172.

26. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1683-1689, CH2/383/3, fols. 9 & 11.

27. NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1683-1689, CH2/383/3, fol. 9.

28. Statistical Account of Scotland, (1791), vi, 506.

29. New Statistical Account of Scotland, (1839), i, 22.

Bibliography

NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-1671, CH2/383/1.

NRS Liberton Kirk Session, 1683-1689, CH2/383/3.

NRS Papers of Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, GD103/2/45.

NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2.

Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, 1839-45, ed. T. Thomson (Bannatyne Club), Edinburgh.

Charters of King David I : the written acts of David I King of Scots, 1124-53 and of his son Henry Earl of Northumberland, 1139-52, 1999, ed. G.W.S. Barrow, Woodbridge.

Cowan, I.B., 1967, The parishes of medieval Scotland, (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh.

Donaldson, G., 1949, Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices, (Scottish History Society), Edinburgh.

Liber Cartarum Sancte Crucis, 1840, ed. C. Innes, (Bannatyne Club), Edinburgh.

Liber Officialis Sancti Andree, 1845, (Abbotsford Club), Edinburgh.

Kirk, J., 1995, The books of assumption of the thirds of benefices, (British Academy) Oxford.

Mackinlay, J.M, 1910, Ancient Church Dedications in Scotland. Scriptural Dedications, Edinburgh.

New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45, Edinburgh and London.

Protocol Book of John Foular, 1503-1513, 1940, ed. W. McLeod (Scottish record Society), Edinburgh.

Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-9, ed. J. Sinclair, Edinburgh.

Architectural description

Two fragments of crosses that have been found in the vicinity, and that are now in the National Museum of Scotland, may point to Early Christian worship on this site. One was found in a wall adjoining Liberton Tower and presented to the museum in 1863, and the other was found in a garden rockery and given to the museum in 1893.(1)

The medieval church originated as a chapel of Edinburgh St Cuthbert’s Church, and passed with that church when it was granted to the Augustinian abbey of Holyrood by David I at a date between 1128 and 1136. It achieved parochial status before the Reformation, with the cure a vicarage perpetual, though it is likely that it was served by one of Holyrood’s canons.(2)

In 1567 Bishop Adam Bothwell of Orkney, who was commendator of Holyrood, said that he had repaired the church.(3) Despite those repairs, by 25 July 1598, it could be said that it was ruinous and letting in the water.(4) Further repairs were required in the course of the seventeenth century: to the steeple at several dates in the 1640s,(5) and to the south aisle on 2 September 1683.(6)

A description of the church published in 1792 by Thomas Whyte, the parish minister,(7) said that there were two aisles on the south side of the church. Those were the Stainhouse aisle and Gavin’s aisle, the latter being a burial place that did not communicate with the church itself, and which had an armorial tablet dated 1632. On the north side of the church were three aisles. The easternmost was built for Sir John Baird of Newbyth in 1736, and the westernmost by Lord Somerville and Tomas Rigg of Morton in 1724. The middle aisle belonged to Sir Alexander Gilmour of Craigmillar, and was said to be vaulted and of an early date. Internally, there was an east gallery that had been built by Sir John Wauchope in 1640, while the Mortonhall gallery at the west end had been built in 1670.

These arrangements are amplified in a plan by the Rev’d John Sime, which appears to show that the core of the church consisted of a rectangular chancel that was slightly narrower than the rectangular nave.(8) This plan indicates that the chancel was occupied by the Niddry loft and the west end of the nave by the Mortonhall loft. The aisles on the north, from east to west, were for Baird of Newbyth, Craigmillar, and Somerville of Drum in a loft over Morton. On the south the east aisle was the burial place of Gavin Nisbet of Muirhouse, and the Gilmerton colliers in a loft over Stainhouse.

A view of the church by Andrew Kerr from the south shows it before its rebuilding.(9) A south transeptal aisle about half-way down its length, which rose to the same height as the main body, was presumably the Stainhouse Aisle. East of that aisle is what appears to be a roofless burial enclosure, which was presumably Gavin’s Aisle. Towards the west end of the south flank is a porch with a round-arched doorway of four orders which it appears possible may be an ambitious opening of Romanesque form. At the west end is a square tower that is intaken to an octagon and capped by a round top stage with a dome of ogee profile. There have clearly been many post-Reformation modifications, as seen most clearly in the forestairs to the lofts in the eastern limb and the south transeptal aisle, and the superstructure of the tower.

If the central north aisle was of early origin, as appears to be suggested by Whyte, it may be seen as a possibility that the central south aisle was also of Pre-Reformation date. On the basis of Whyte’s description of 1792 and Kerr’s view it therefore appears at least a possibility that in its final medieval state the church had achieved an irregular cruciform state, with a south porch and west tower, against which three further aisles had been added in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The medieval church was replaced by a new building ‘erected in 1815 from a plan by James Gillespie Graham’.(10) The new church, which is built of grey ashlar, was set out to a T-plan, aligned parallel to the road, and thus with an axis of east-north-east to west-south-west. The aisle is on the ‘north’ side, and there is a tower at the ‘west, end. The main face, to the south, is of six bays, with entrances in the second and fifth bays, over which the crenellated wall head rises into steep gables with cross finials. There is ample provision of the simplified tracery favoured by Gillespie Graham. The church was recast in 1882 and again in about 1934.(11)

Notes

1. J. Romilly Allen, The Early Christian Monuments of Scotland, Edinburgh, 1903, pt. 3, pp. 424-26.

2. Ian B. Cowan, The Parishes of Medieval Scotland (Scottish Record Society), 1967, p. 132.

3. Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, ed. T. Thomson (Bannatyne Club). 1839-45, vol. 1, pp. 162-63 and 167-68.

4. National Records of Scotland, Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fols 240-41.

5. National Records of Scotland, Liberton Kirk Session, 1639-71, CH2/383/1, fols 37, 43, 57, 60 and 61.

6. National Records of Scotland, Liberton Kirk Session, 1683-89, CH2/383/3, fol. 9.

7. Thomas Whyte, ‘An Account of the Parish of Liberton’, Archaeologia Scotica, vol. 1, 1792, pp. 292-388, at pp 295-98.

8. Published in George Good, Liberton in Ancient and Modern Times, Edinburgh, 1893, and re-drawn and published in Howard Colvin, Architecture and the After-Life, New Haven and London, 1991, fig. 272.

9. National Monuments Record of Scotland, SC565208.

10. New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45, vol. 1, pp. 11 and 22.

11. John Gifford, Colin McWilliam and David Walker, The Buildings of Scotland, Edinburgh, Harmondsworth, 1984, p. 484.

Map

Images

Click on any thumbnail to open the image gallery and slideshow.