- Navigation:

- Back to the Corpus index page

- RSS

Edinburgh St Cuthbert's Parish Church

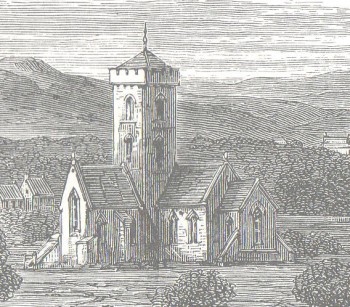

Edinburgh St Cuthbert, 'Old and new Edinburgh' after Clerk of Eldin

- Dedication: St Cuthbert

- Diocese of St Andrews

- Deanery of Linlithgow

- NT 24851 73554

Summary description

The medieval church appears to have had a south transeptal aisle and a tower at the south-west corner. It was rebuilt in 1773-75, and the tower heightened in 1789. The main body of the church was again rebuilt in 1892-95, retaining the tower.

Historical outline

Dedication: St Cuthbert

What came to be known as the church of St Cuthbert beneath the Castle appears to have originated as the mother-church – possibly in origin a late Anglian period minster – for an extensive paruchia that stretched west from Edinburgh to the River Almond and south to the Pentland Hills. It was evidently still a church of more than just parochial importance early in the reign of King David I (1125-53), for he bestowed on it lands that extended round the foot of the castle rock at Edinburgh ‘from the spring that rises at the corner of the king’s garden’ to the road below the castle on the east side.(1) Shortly after the foundation of the Augustinian abbey of Holyrood in 1128, King David bestowed the church of St Cuthbert on the new monastery, together with all of its associated lands and its dependent chapels of Corstorphine and Liberton, and all of the rights and renders due to it.(2) Confirmation of their possession of St Cuthbert’s was given by Bishop Robert of St Andrews by c.1130.(3)

It appears that the whole church and its revenues were annexed to the abbey from the time of these grants, and successive confirmations of possession were received from kings of Scots, bishops of St Andrews and popes.(4) Having been confirmed by him to the abbey in 1248, it was only in 1251 that Bishop David de Bernham instituted a vicarage settlement.(5) The parsonage was annexed to Holyrood from that point, with a perpetual vicarage valued at 25 merks annually instituted to serve the cure. For much of the remainder of the pre-Reformation, however, normal practice appears to have been for the vicarage to be served by one of the canons of the abbey. In 1420, a supplication for provision to the vicarage made to the pope articulated that claim, stating that the church, which was a perpetual vicarage, was ‘wont to be ruled by canons regular of the monastery of Holyrood’.(6) There are several further explicit references to canons of Holyrood holding the vicarage through the fifteenth century, and in 1470 King James III specifically petitioned the pope that no-one other than a canon of Holyrood should be provided to serve in St Cuthbert’s (or any of the other churches appropriated to the abbey).(7) At the Reformation, it was still a perpetual vicarage, held by Mr Archibald Hamilton and valued at £33 6s 8d.(8)

Bishop David consecrated the church of St Cuthbert below the castle in March 1242.(9) The vicarage of St Cuthbert sub castro was recorded in the rolls of the papal tax-collector in Scotland in the mid-1270s, valued at 6s 8d taxation for the first year.(10) Other than references to provision of vicars down to the later fifteenth century, however, there is little further notice of this rich and well-located church until the last quarter of the 1400s.

It is in the 1480s that evidence emerges of the patronage shown towards the church by various benefactors amongst the suburban aristocracy and urban elite of Edinburgh. Three subsidiary altars are recorded as being founded and endowed by such individuals. The earliest reference to an additional altar dates from 3 July 1486, with confirmation at mortmain under the Great Seal by King James III on25 October 1487, when William Towers of Inverleith and his wife, Agnes Hume, endowed a chaplainry at the altar of St Anne, mother of the Virgin.(11) In 1558 it was recorded that George Towers was patron of this altar, which had been founded by his ancestors in the aisle of St Anne on the north side of the parish church.(12) The second recorded altar, dedicated to Holy Trinity, was endowed for support of a chaplainry on 10 December 1488 by Master Alexander Currour, vicar of Livingston, with confirmation at mortmain under the Great Seal being received on 2 January 1488/9.(13) This may have been the most substantially-endowed of the chaplainries in the church, meriting a separate item in the Books of Assumption after the Reformation. At that time the Trinity altar, held by Simon Blyth (who also held the chaplainry of St Salvator in the kirk of St Giles), was valued at £8 12s 2d.(14)

No record survives of the foundation of the third altar or of particular endowments made towards it, but the document in which it is referred to provides some interesting detail on the physical form of the church and on burials within it. On 28 February 1541, Euphemia Durham, heiress of John Durham, agreed to her husband James Lowrason’s disposal to a certain John Scot of a ‘throcht stone’ (a ledger slab in the floor of the church) and its associated burial lair. This lair was located in St Cuthbert’s ‘near the altar of St NInian’, which was described as being ‘in the cross kirk of the same’,(15) implying that the late medieval church was a cruciform building.

Notes

1. G W S Barrow (ed), The Charters of King David I (Woodbridge, 1999), no.71; Liber Cartarum Sancte Crucis (Bannatyne Club, 1840), no.3 [hererafter Holyrood Liber].

4. Holyrood Liber, nos 13, 76, appendix no.8; Regesta Regum Scottorum, ii, The Acts of William I, ed G W S Barrow (Edinburgh, 1971), no.39; Scotia Pontificia: Papal Letters to Scotland before the Pontificate of Innocent III, 1982, ed. R. Somerville, Oxford, 1982), no.53.

5. Holyrood Liber, nos.75, 76.

6. Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome, i, 1418-1422, eds E R Lindsay and A I Cameron (Scottish History Society, 1934), 202.

7. Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome, v, 1447-1471, eds J Kirk, R J Tanner and A I Dunlop (Glasgow, 1997), nos 967, 1454.

8. J Kirk (ed), The Books of Assumption of Thirds of Benefices (Oxford, 1995), 105.

9. A O Anderson (ed), Early Sources of Scottish History, ii (Edinburgh, 1922), 521.

10. A I Dunlop (ed), ‘Bagimond’s Roll: Statement of the Tenths of the Kingdom of Scotland’, Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, vi (1939), 55, 56.

11. Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum, ii, 1424-1513, ed J B Paul (Edinburgh, 1882), no.1692 [hereafter RMS, ii].

12. Protocol Book of Mr Gilbert Grote, 1552-1573, ed W Angus (Scottish Record Society, 1914)), nos 152, 153.

14. J Kirk (ed), The Books of Assumption of the Thirds of Benefices (Oxford, 1995), 128-9.

15. NRS Protocol Book of Edward Dickson, 1537-45, NP1/5B, folio 139.

Summary of relevant documentation

Medieval

Synopsis of Cowan’s Parishes:

Granted by David I to Holyrood in 1128, with its chapels of Corstorphine and Liberton. A vicarage settlement took place in 1251 after which the parsonage remained with the abbey, although the vicarage was normally served by one of the canons.(1)

1128x47 Church given to the abbey by David I, with chapels of Corstorphine and Liberton, the kirktown, the land on which the church itself stood, land under the base of the castle crag and half the fishing in Leith harbour.(2)

1140x53 Church confirmed to abbey by Roger, bishop of St Andrews.(3)

1164 Chapel confirmed with 2 oxgangs and 6 acres by Alexander III.(4)

1165x66 Church included in confirmation by Richard, bishop of St Andrews of all the churches given to the abbey by David I, Malcolm IV and bishops Aernald and Robert of St Andrews.(5)

1165x71 Church confirmed to the abbey by William I.(6)

1247 Church included in a papal confirmation of the possessions of the abbey by Innocent IV.(7)

1248 Church included in confirmation of possessions of the abbey by David de Bernham, bishop of St Andrews.(8)

1251 Vicarage settlement by David de Bernham, bishop of St Andrews; parsonage with the abbey; perpetual vicarage valued at 20 marks.(9)

1268 Church included in confirmation of the possessions of the abbey in the diocese of St Andrews by Gameline, bishop of St Andrews.(10)

1420 Perpetual vicarage described as ‘wont to be ruled by canons regular of Holyrood’, Vacant on Henry de Dryden (illegitimate) becoming abbot, John de Inverkeithing (canon, Order of St Augustine) is provided.

1422 John resigns in favour of another canon, John de Bening.(11)

1432 John de Inverkeithing is perpetual vicar again on resignation of Peter de Bening. [sic, John?] In the same year John is promoted to abbacy of Scone and another canon Patrick Sharp provided to church.(12)

1436 David de Ramsey (canon of priory of St Andrews), disputes legitimacy of possession by Sharp and supplicates for church [not clear whether successful or not].(13)

1464 John Crawford (canon of Holyrood and son of a monk) provided to church.(14)

1470 James III petitions for a confirmation that no secular or regulars of any order should be allowed to obtain the parishes churches of Falkirk, Tranent, St Cuthbert’s, Kinghorn Easter, Kinniel and others which are wont to be held by the canons of Holyrood.(15)

1492 & 1494 Local land disputes settled during Sunday mass at the High altar.(16)

1501 & 1503 The late Patrick Sharp is vicar of church; John Bell is described as one of the ‘masters of the fabric of the church’.(17)

1533 Alexander Wilkinson provides a gift of £10 of annual rents to sustain a perpetual chaplain in church of St Cuthbert (no altar specified).(18)

Altars and chaplaincies

Holy Trinity

1488 Chaplaincy founded at the Trinity altar by Alexander Currour, vicar of Livingstone.(19)

St Anne

1486 Foundation of chaplaincy by William Touris of Inverleith and Agnes Hume his wife.(20)

1558 George Towris of Inverlieth, patron of the chaplainry of St Anne, ‘founded by his predecessors in the aisle of St Ann on the north side of the parish church’. John Duncanson is chaplain.(21)

St Ninian

1541 (28 Feb) Euphamia Durham, heir of John Durham, consents and assents that her husband James Lowrason has given to John Scot possession of a throcht stone and lair in the church of St Cuthbert’s under the castle, near the altar of St NInian in the cross kirk of the same.(22)

Post-medieval

Books of assumption of thirds of benefices and Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices: The Parish church parsonage with Holyrood, set for £252 3s 4d. Vicarage held by Archibald Hamilton, £33 6s 8d.(23)

Altars and Chaplainries

Trinity Altar, pertaining to Simon Blyth, value £8 12s 2d.(24)

Account of Collectors of Thirds of Benefices (G. Donaldson): Third of vicarage £6 13s 4d.(25)

1560 (20 Dec) William Harlaw (minister) and Robert Fernley of Braid represented the church at the first meeting of the General Assembly in Edinburgh.(26)

1567 Adam Bothwell, bishop of Orkney (and commendator of Holyrood) hauled in front of the General Assembly accused of allowing parish churches to decay. He commented that he had repaired St Cuthbert’s and Liberton churches which had been in poor repair.(27)

1597 (6 Dec) Visitation of the West Kirk of Edinburgh (St Cuthbert’s) finds the kirk yard dykes down and asks the lord of Braid to see to it.(28)

1598 (17 July) Visitation of the kirk by the Presbytery of Edinburgh finds that William Ard (minister) is competent and the kirk yard dykes are in disrepair.(29)

Statistical Account of Scotland: [No reference to church building]

New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845):‘The present church was built in 1775’.(30) [no reference to remains to earlier building]

Architecture of Scottish Post-Reformation Churches: (George Hay): 1789 steeple, H. Weir, architect; remainder 1893, 1827 watch house.(31)

Notes

1. Cowan, The parishes of medieval Scotland, 177.

2. Charters of David I, no. 147.

11. CSSR, i, 202-03, 216-17 & 308, CPL, vii, 454.

15. CSSR, v, no1454, CPL, xii, 735.

16. Prot Bk of James Young, 1485-1515, nos. 560 & 769.

17. Prot Bk of John Foular, 9 March 1500 to 18 September 1503, nos. 110 & 253.

18. Prot Bk of John Foular, 1528-34, no. 528.

21. Prot Bk of Gilbert Grote, 1552-1573, nos. 152 & 153.

22. NRS Prot Bk of Edward Dickson, 1537-45, NP1/5B, fol. 139.

23. Kirk, The books of assumption of the thirds of benefices, 91-93 & 105.

25. Donaldson, Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices, 27.

26. Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, i, p.3.

27. Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, i, pp. 162-63 & 167-68.

28. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol. 216.

29. NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2, fol. 239.

30. New Statistical Account of Scotland, (1845), i, 664.

31. Hay, The Architecture of Scottish Post-Reformation Churches, pp. 81, 119,164, 175, 189, 190, 236 & 265.

Bibliography

NRS Presbytery of Edinburgh, Minutes, 1593-1601, CH2/121/2.

NRS Prot Bk of Edward Dickson, 1537-45, NP1/5B.

Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, 1839-45, ed. T. Thomson (Bannatyne Club), Edinburgh.

Calendar of entries in the Papal registers relating to Great Britain and Ireland; Papal letters, 1893-, ed. W.H. Bliss, London.

Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome 1418-22, 1934, ed. E.R. Lindsay and A.I. Cameron, (Scottish History Society) Edinburgh.

Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome 1423-28, 1956, ed. A.I. Dunlop, (Scottish History Society) Edinburgh.

Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome 1433-47, 1983, ed. A.I. Dunlop and D MacLauchlan, Glasgow.

Calendar of Scottish Supplications to Rome 1447-71, 1997, ed. J. Kirk, R.J. Tanner and A.I. Dunlop, Edinburgh.

Charters of King David I : the written acts of David I King of Scots, 1124-53 and of his son Henry Earl of Northumberland, 1139-52, 1999, ed. G.W.S. Barrow, Woodbridge.

Cowan, I.B., 1967, The parishes of medieval Scotland, (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh.

Donaldson, G., 1949, Accounts of the collectors of thirds of benefices, (Scottish History Society), Edinburgh.

Hay, G., 1957, The Architecture of Scottish Post-Reformation Churches, 1560-1843, Oxford.

Kirk, J., 1995, The books of assumption of the thirds of benefices, (British Academy) Oxford.

Liber Cartarum Sancte Crucis, 1840, ed. C. Innes, (Bannatyne Club), Edinburgh.

New Statistical Account of Scotland, 1834-45, Edinburgh and London.

Protocol Book of Mr Gilbert Grote, 1552-1573, 1914, ed. W. Angus (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh.

Protocol Book of James Young, 1485-1515, 1952, ed. G. Donaldson (Scottish Record Society), Edinburgh.

Protocol Book of John Foular, 1503-1513, 1940, ed. W. McLeod (Scottish record Society), Edinburgh.

Protocol Book of John Foular, 1528-34, 1985, ed. J. Durkan (Scottish record Society), Edinburgh.

Regesta Regum Scottorum, Acts of William I (1165-1214), 1971, Edinburgh.

Scotia pontificia papal letters to Scotland before the Pontificate of Innocent III, 1982, ed. R. Somerville, Oxford.

Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-9, ed. J. Sinclair, Edinburgh.

Architectural description

This parish was in existence in the reign of David I by a date between 1128 and 1136, when he granted it to the Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood, along with its chapels of Corstorphine and Liberton. A vicarage settlement was established in 1251, which was usually served by one of Holyrood’s canons.(1)

There may have been some work in progress in the first years of the sixteenth century when John Bell is mentioned as one of the masters of the fabric.(2) Something is known of the position of at least two of the altars in the medieval church, with that of St Ninian referred to as being in the cross kirk,(3) and that of St Ann being on the north side.(4)

Following the Reformation it is likely that no more than the nave remained in use In 1567 some repairs were said to have been carried out by Bishop Adam Bothwell of Orkney, who was also commendator of Holyrood.(5) The abandoned choir was soon adapted for burials, and came to be enveloped by enclosures and vaults for that same purpose. One vault still survives beneath the north side of the church, that of the Nisbet of Dean family; a handsome baroque armorial cartouche with the date 1692 is built into the wall of the church above the steps leading down to that vault.

No identifiable traces remain of the medieval church. The best representation of it before its destruction is on Gordon of Rothiemay’s view of Edinburgh of 1647, which shows a rectangular core with a south transeptal aisle and a tower at what appears to be the south-west corner.

The church evidently suffered particularly grievously from its proximity to the castle at periods when the castle was under attack, especially during the Cromwellian siege of 1650, and the siege at the time of the Glorious Revolution of 1689. By 1772 the building was deemed to be too dangerous to continue in use, and in 1773-5 James Weir replaced it with a simple preaching hall with a western annexe containing a stair to the galleries;(6) on its west face, above a Venetian window at gallery level, is a sundial with the date 1774.(7)

In 1789 it was decided to raise the western annexe into a full tower culminating in a steeple, which was built by Alexander Stevens.8 By the 1880s the church was once again deemed to be unsafe. After considering the possibility of repairs, the main body of the church was rebuilt in an opulent manner by Hippolyte Blanc between 1892 and 1895. Only the west tower from the previous church was retained, and it was balanced at the east end of the new building by an apse, transepts and a pair of turrets capped by cupolas.

Notes

1. Ian B. Cowan, The Parishes of Medieval Scotland (Scottish Record Society), 1967, p. 177.

2. Protocol Book of John Foular, 1500-1503, vol. 1, ed. Walter Macleod, 1930, nos 110 and 253.

3. National Records of Scotland, Protocol Book of Edward Dickson, 1537-45, NP1/5B, fol. 139.

4. Protocol Book of Edward Grote, 1552-1573, ed. William Angus (Scottish Record Society), 1914, nos152 and 153.

5. Acts and Proceedings of the General Assemblies of the Kirk of Scotland, ed. Thomas Thomson (Bannatyne Club), vol. 1, pp162-63 and 167-68.

6. National Records of Scotland GD 69/210.

7. Published accounts of the church include: William Sime, History of the Church and Parish of St Cuthbert, Edinburgh, 1829; George Lorimer, Leaves from the Buik of the West Kirke, Edinburgh, 1885; Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 1951, pp. 185-87; John Gifford, Colin McWilliam and David Walker, the Buildings of Scotland, Edinburgh, Harmondsworth, 1984, pp. 274-76.

Map

Images

Click on any thumbnail to open the image gallery and slideshow.