The legend of the Passion of the Crucifix arrived in Western Europe with the Second Council of Nicaea (787). This text recounts a Jewish blasphemy concerning the image of Christ on the Cross, which had occurred in Beirut. The story goes that at a dinner at someone’s house in Beirut, a group of Jews noticed a Crucifix hanging on the wall (apparently left by the previous owner). Deciding to reproduce the act of their ancestors, the Jews crucified the Crucifix again. The image suddenly started bleeding, with water also coming out along with the blood. Astonished, the Jews brought both the water and the blood to the Synagogue, remembering that the Christians declared they can heal. Indeed, healing miracles then occured there, leading to the conversion of all witnesses to Christianity. This extraordinary text, known as the Beirut legend, was disseminated through the Occident in the Latin translation of the Nicaean acts made by Anastasius the Librarian around 872.

Christ of the Cerdanya, wood sculpture from second half of the 12th century, now in Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Image courtesy of Web del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya de Barcelona, www.museunacional.cat. Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Several important issues come out from this text: the “sacred” and its boundaries, the “miraculous” and the witnesses of the miracle, the power of the image and its agency, the visualising of the invisible. The text tells us about the image and the image emerges from the text—in this entanglement a new comprehension of the Crucifix takes shape. The increasing interest in the relics during the tenth and the eleventh centuries was obviously of particular importance to the developing veneration of the Crucifix, and the blood from Beirut’s Imago Domini became one of the major relics of Christ in Western religious thought. The multiple vessels containing the sacred blood of Christ were spread across Western Europe (with testimonies from Reichenau and Oviedo already possessing them in the eleventh century).

Apparently, the diffusion of the text of the Beirut legend in different religious communities galvanized a particular veneration towards the Crucifix. The passion of Christ gained an important place in Carolingian theological discourse, focused primarily on the development of Christological doctrines. One hundred years later, at the end of the tenth century, some liturgical books mention the feast called Passio Imaginis Domini. The first regions in the Western Europe which attested the liturgical celebration of this feast were Catalonia and Aquitania.

The lectionary from Saint-Martial de Limoges (10th century) contains the text of the Beirut legend: “Legatur sermo sancte memorie patris viri Athanasii de Imagine Domini nostri Iesu Christi […] quod factum est miraculum magnum in civitate Berito”. This manuscript does not put the text into correlation to any specific data. But already from the end of the tenth century, the Catalan liturgical books find the place for commemorating this “miraculum magnum” on the 9th November.

The earliest Catalan martyrologies from the end of the tenth and beginning of the eleventh centuries mention this feast in the margins (as in the case of the Girona and Vic martyrologies). From the eleventh century on, the feast is copied into the main text and thus seems to be fully integrated as a part of liturgical celebrations (in the martyrologies of the chapter of Vic and in monastic manuscripts from Sant Cugat del Vallès, and Santa Maria de Ripoll and Santa Maria de Serrateix). At the same time, the calendars from the Catalan region also mention this feast during the eleventh and twelfth centuries (Girona, Montserrat). As often is the case with Catalan religious institutions, the veneration touched both secular and regular religious communities.

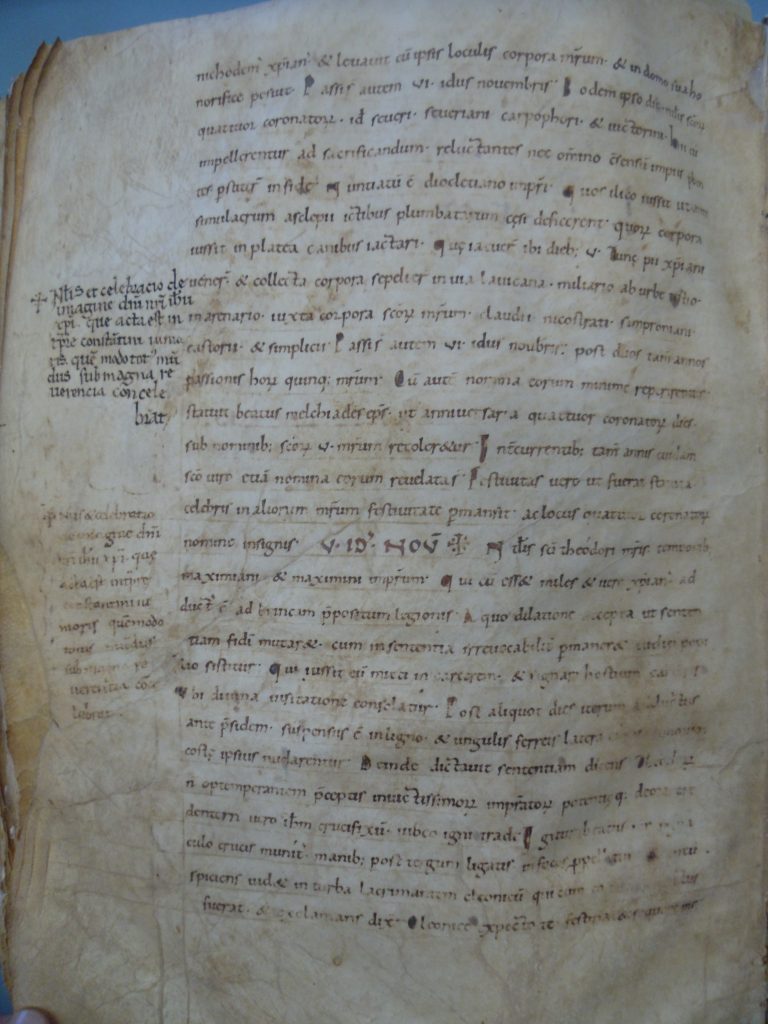

Vic Arxiu i Biblioteca Episcopal MS128A f. 129v.

Coming back to the first Vic martyrology (compiled between 993 and 1010), an interesting fact concerns the double mention of this feast in the margin. If the low margin seems to be written in a Carolingian minuscule very close the original one, possibly not much later, the upper one is written in Gothic script and repeats verbatim the lower version. Leaving a possible lack of attention aside, the main reason for such an addition might be the importance of Christ’s feast and of the celebration of his sacred image. Besides, this mention from the Vic martyrologies does not correspond to others (respectively in Girona, Sant Cugat and Santa Maria de Serrateix manuscripts). These last ones refer only to the fact of celebrating the Passion of the Image of Christ that happened in Beirut, while all Vic texts insist more on the solemnity of this feast: “Natalis [or festivitas] et celebratio de Ymagine [Ymaginis] Domini que[a]m totus mundus sub magna reverentia concelebrat”.

There have not been many texts of Athanasius’s legend found in the Catalan archives. One version is conserved in the Lleida archive in a lectionary with the provenance from Roda d’Isàvena and is dated to the eleventh century. The text is slightly different from the earliest Limousin one but points out the celebration of the feast Passio Imaginis Domini on November 9th. The established liturgical veneration of this feast throughout the Catalan counties can thus be confirmed.

The complex phenomenon of the Beirut legend promoted devotion to the miraculous Crucifix on several levels: first, in liturgical field via the creation of a new liturgical feast and the diffusion of new lectures in books for mass and office; second, in popular devotion through the diffusion of relics with the blood of Christ (in the thirteenth century, this relic would be proclaimed by Thomas Aquinas as the only possible blood relic of Christ apart from the wine transubstantiated during the Mass). Finally, having emerged and spread out during the years of the iconoclasm controversy, the Beirut legend might have defined the major tendencies in medieval art. Taking into account these multiple and rich issues, the paradoxical status of Catalonia as compared to other European regions, with its early liturgical veneration of Passio Imaginis Domini and relatively late blossoming of the well-known Catalan Crucifixions fosters significant interest and is still to be examined.