The centrepiece of the Chronicle of Alfonso III, written in the late 9th or early 10th centuries, is the description of a certain Pelayo and his rebellion against the Saracen foreign rulers of the Iberian Peninsula. Pelayo, as the chronicle describes it, led a small group of Asturians in the pathless mountains in the North of the Iberian Peninsula, where they were able to defeat and put to flight the greater forces of the Saracens in the famous battle of Covadonga. The depiction of Pelayo offers parallels to several biblical rulers and, furthermore, identifies him as legitimate successor of the last Visigothic kings. Thus, in the figure of Pelayo “profane” and biblical elements are united. This combination marks him out as an “Asturian hybrid of Moses and Asterix”, as Peter Linehan has written. In the following, the different attributes and characterizations of Pelayo will be shown and interpreted concerning their meaning in the grant narrative of the Chronicle of Alfonso III.

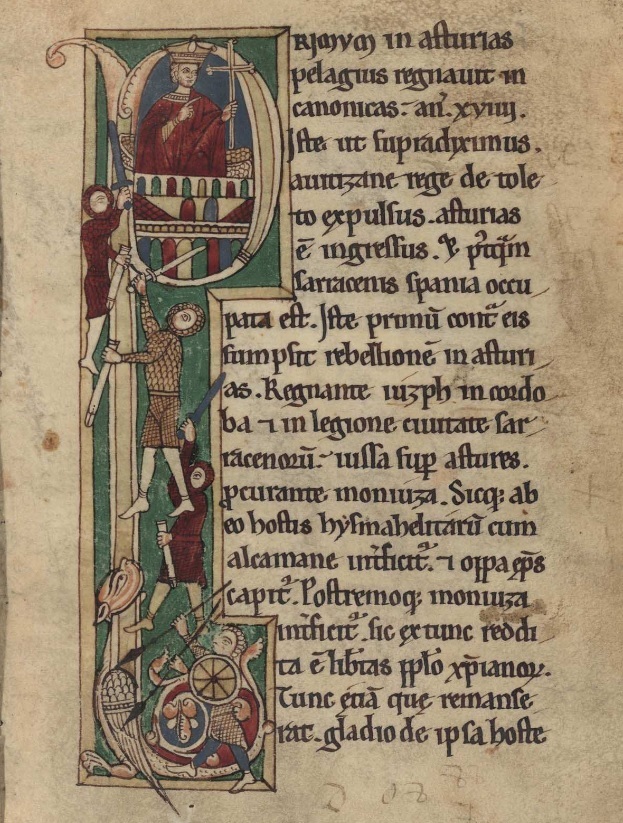

Pelayo in a 12th-century version of the Chronicle of Albelda. Trusting in God (pointing at the cross), he defeats the attacking Saracens (stigmatized with a round shield for non-Christians). Corpus Pelagianum, Matr. BN 2805, fol 23r. Image credit Biblioteca Nacional de España, image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The so-called “Rotense-version” of the chronicle offers some biographical data on Pelayo. He was sword bearer of the last two Visigothic kings, Wittiza and Roderic. Hence, he had a high position in the former kingdom, was undoubtedly of royal origin and, therefore, was legitimized as new ruler. When the Saracens invaded the Visigothic kingdom, Pelayo was forced to flee with his sister into the north of the Peninsula. Even though he was fleeing from the invaders, he became the messenger of the Saracen governor of Gijón, called Munuza. This Munuza sent Pelayo off to Córdoba so he could marry Pelayo’s sister while he was away. Pelayo, realizing Munuza’s deception, tried to return to Gijón and prevent the wedding. Yet, Saracen forces prevented him from reaching Gijón and pursued him. As Pelayo was hiding in the mountains, a crowd of Christians joined him and made him their princeps.

Hearing of this development, the Saracens sent an army of 187,000 men to the mountains. They encountered Pelayo’s group at Covadonga. Bishop Oppa, a son of the former king Wittiza and a collaborator with the Saracens, tried to convince Pelayo to give up. During a dialogue, Pelayo reminded Oppa of the words of the New Testament, that out of a small mustard grain a large plant can grow (Mt 13, 31 sq.; Mc 4, 30–32; Lc 13, 18 sq.; Lc 17, 6) and just like this, the small group of Christians would be able to defeat the larger Saracen force. Despite all Oppa’s rhetorical efforts, the battle began and the God-fearing Christians were able to kill 124,000 of the Saracens. These drastic casualties led the surviving Saracens to retreat. Although the remaining 63,000 Saracens escaped, they could not be saved. A landslide smashed them, hurled them into a river and buried them all. As the chronicler interprets this phenomenon, God himself made this happen to punish the Saracens for their sins against the Christians. He compares this divine punishment with a famous Old Testament passage: “Do not think this to be unfounded or fictitious. Keep in mind that he who once parted the waters of the Red Sea so that the children of Israel might cross, has now crushed, with an immense mass of mountain, the Arabs who were persecuting the church of God” (Translation by Kenneth Baxter Wolf: Conquerors and Chroniclers, p. 136).

The reference to the book of Exodus typologically identifies the Arabs as new Egyptians. The burying landslide echoes the floods of the Red Sea, drowning the enemies of the Chosen People and, therefore, Pelayo becomes a new Moses, leading his people out of misery. However, Moses is not the only figure that typologically coincides with Pelayo. As Alexander Pierre Bronisch investigated, Pelayo shows several similarities with Judas Maccabeus or Mattathias. The first won against the overwhelming majority of Antiochus’ troops; the second was hiding in the mountains after he opposed Antiochus. In addition to these Old Testament allusions, the chronicle offers also quotes from the books of Maccabees during the description of the battle.

Furthermore, the story of Pelayo and the battle of Covadonga seems to be influenced by the Old Testament story of Sennacherib and Hezekiah. In the second book of Kings as well as in the second book of Chronicles their story follows the same structure as Pelayo’s: a minority of people trusting in God, a salvation figure that is chosen to lead, an exorbitant majority of enemies (who do not trust in God), the attempt to convince the minority to give up, the denial due to the certainty of having God’s assistance, and finally the defeat of the superiority. What’s more, the numbers of dying Assyrians in the second book of Kings is very close to the Saracen army in the Chronicle of Alfonso III: 185,000 Assyrians died (II Kings 19, 35). We also see this number in the book of Isaiah, with the death of 185,000 Assyrians who were threatening the Israelites (Is 37, 36) and, again, in the second book of the Maccabees (II Mcc 15, 22; 8, 19).

Another Bible allusion is hidden in a number of the Covadonga story. 124,000 killed Arab soldiers seem very similar to the 120,000 soldiers of the army of Midian that were killed by Gideon and his 300 allies, who also believed in God’s mercy (Jdg 8, 4–10). Next to this similarities in quantity and piousness, the designation of the salvation figures is also the same: both are called princeps, not rex. Hence, they were understood as princes, royal rulers but not as kings. The book of Judges, where the episode of Gideon appears, too, tells the story of Israel’s before it became a kingdom. Similarly, this passage of the Chronicle of Alfonso III reports a formation process of a kingdom out of a rebellion, led by a princeps.

Finally, Pelayo is depicted as new King David. During the aforementioned dialogue with Bishop Oppa, he denied the collaboration with the Saracens by quoting a passage from the Psalms in which King David substantiates his fidelity towards God (Ps 88, 33 sq.). Accordingly, Pelayo, the founder of the Asturian Kingdom, is identified with the archetype of all kings: King David, the saviour of the Ark of the Covenant and the defeater of Goliath.

To sum up, the Chronicle of Alfonso III, which was written at the Asturian court around 900, depicted a progenitor of king Alfonso’s III clan, the first ruler of Asturias, Pelayo in whom at least nine characters and typological figures are united: Pelayo is at once a deceived hero, a legitimate successor of the last Visigothic royals, a god-fearing Christian rebel, as well as an anti-type of Moses, Mattathias, Judas Maccabeus, Gideon, Hezekiah and David.

Editions

Die Chronik Alfons’ III. in: Prelog, J. (ed.): Die Chronik Alfons’ III. Untersuchung und kritische Edition der vier Redaktionen, Frankfurt am Main/Bern/Cirencester 1980, pp. 1–67.

Chronica Adefonsi III. in: Bonnaz, Y. (ed.): Chroniques Asturiennes (Fin IXe Siècle). Paris 1987, pp. 31–59 [left hand page, right column; right hand page, left column].

Chronica Adephonsi III. in: Gil, J. (ed.): Chronica Hispana saeculi VIII et IX. Cura et studio, Turnhout 2018, pp. 501–512.

Modern translations

English: K. B. Wolf, Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain (Liverpool, 2011), pp. 129 – 143.

French: Y. Bonnaz, Chroniques Asturiennes (Fin IXe Siècle) (Paris, 1987), pp. 31–59 [left hand page, left column; right hand page, right column].

Spanish: J. Gil Fernández, Cronicas Asturianas. Crónica de Alfonso III (Rotense y «A Sebastián»), Crónica Albeldense (y «Profética») (Oviedo, 1985), pp. 194–222; J. E. Casariego, Crónicas de los Reinos de Asturias y León (León, 1985), pp. 49–77.

Patrick S. Marschner, M.A.; Institute for Medieval Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, FWF-Project: Bible and Historiography in Transcultural Iberian Societies, 8th to 12th Centuries. PhD student at the University of Vienna.

Patrick S. Marschner, M.A.; Institute for Medieval Research at the Austrian Academy of Sciences, FWF-Project: Bible and Historiography in Transcultural Iberian Societies, 8th to 12th Centuries. PhD student at the University of Vienna.