The Bohemian Duke Wenceslas has been closely associated with Christmas ever since 1853, when John Mason Neale set his ‘Good King Wenceslas’ to the tune of a medieval spring carol. Despite Neale’s effort being described as ‘ridiculous’, ‘doggerel’ and ‘poor’ by critics of the time, it has become a ubiquitous part of December for many, also giving rise to what is (to my knowledge), the only joke to combine tenth-century fratricide and pizza.

But we know almost nothing of the life of the ‘real’ Duke Wenceslas, Václav, beyond his martyrdom in 935 at the hands of his brother, Boleslav I. Like so many royal saints, the narratives of their lives as preserved by hagiographers are so shaped by the genre and tropes of saintly behaviour that it is difficult to distinguish anything of the personal. Wenceslas is no exception, and four hagiographical texts were written within one hundred years following his martyrdom, with complicated chronologies and dependencies on each other.

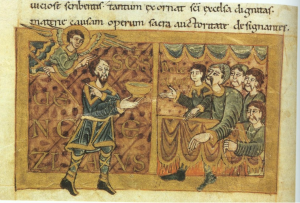

Wencelas attends a banquet with his brother and guests, from Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Guelf. 11,2 Augusteus 4, fol. 20v, CC BY-SA 4.0, Image Credit Wikimedia Commons.

I want to focus today on the relationship between law, justice and kingship as presented in one of these texts, written by Bishop Gumpold of Mantua. Gumpold completed his work before 983, and wrote at the behest of ‘the most victorious and august Emperor Otto II’. Ian Wood comments that Gumpold’s additions and editorial choices give the impression that he was writing a mirror for princes (a genre of text intended as a guide for royals) either for Otto II himself or possibly for his son.

Gumpold’s presents the ‘king’ (as he became in these texts) as a reluctant participant in the court, who abhorred all forms of physical punishment, but was constrained by fear for his citizens if did not ‘impose the fitting law of civil force’. In his youth Wenceslas thus ‘strove to moderate the legal decrees with his lordly will for the common benefit of the citizens and the court. He was prudent in judgments and ready to show mercy to everyone, easily persuaded to pardon punishments for the lamentable offences of prisoners, and opposed to all types of sentences that included corporal chastisement’. Thus far, Wenceslas appears as a merciful and benevolent ruler, a depiction certainly not unique to this work. But Gumpold continues:

The lifestyle of this most blessed young man, adorned by such brilliant gems of virtue, was so eagerly devoted to this exertion of poetry that, whenever the appointed court of judges and commoners issued edicts concerning the public enforcement of hearings and settlements, and he knew beforehand something concerning the judgment, then if someone arrested for a crime were brought before him, condemned by the judgment of his accusers, he would walk out safely from the midst of his verdict even if he had been rightfully sentenced to capital punishment; and if the merciful ruler realised that he could not manage to snatch the accused from the terrible law, neither by altering the force of the law nor by moving the judges by his pleas to liberate him, and he still wanted to prevent that he himself and the holy gaze should be darkened by a bloody massacre, he by all means provided an excusable reason to overthrow the judgment and the sentence, since he followed in a salutary way the common sense and the evangelical mandate, which says: “Judge not, lest ye be judged: condemn not, and ye shall not be condemned” … (Luke, 6:37) [He] most benevolently forbore to punish the accused that were noted down for execution, condemned for their crimes. And lest the infamous memory of tortures should persist, he ordered that all gallows … should be destroyed, and he did not allow them to be set up again as long as he lived’ (transl. Marina Miladinov)

Gumpold’s description of Wenceslas and his attitude to the law, at least in his in his early life, is very unusual. Wenceslas seeks not simply to right wrongs or banish corruption from the systems of justice in his kingdom, but instead apparently to dismantle the system completely, rejecting all forms of physical coercion against the rich and poor. This representation runs contrary to the currents of conceptions around justice around the turn of the millennium. From the time of Charlemagne blinding had become a punishment increasingly associated with royal and imperial power, a demonstration of mercy that may seem horrifying to modern sensibilities but at the time was perceived to be the compassionate option, granting the criminal their life (in theory if not in practice). In England there was a similar movement towards non-lethal corporal punishment from the tenth century onwards. Lawmakers still expected those undergoing so-called ‘comprehensive’ mutilation to die, just as if they had been sentenced to execution, but the time between mutilation and death allowed them to atone for their crimes and save their souls. In time, comprehensive mutilation gave way to non-fatal mutilation. Wenceslas, in contrast, rejects all forms of bodily harm.

Cardinal Miloslav Vlk with the skull of Saint Wenceslaus during a procession on September 28, 2006, CC BY-SA 3.0, Image Credit Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, we return to the idea that Gumpold’s work was at least partly intended as a mirror for princes. But Gumpold’s depiction does not align with the standard depictions of royal justice in this genre either, which tended only to emphasise the importance of being a fair judge. In the seventh-century ‘On the twelve abuses of the world’, a text that had great popularity in the ninth-century Carolingian court, kings are exhorted to not allow perjurers or murderers to live and to judge without regard to whether a criminal was rich or poor. In Canaparius’ Vita for Adalbert of Prague, meanwhile, a text composed shortly after Gumpold’s floruit, it is said that Adalbert taught Otto III much, including how to be a just judge.

So how does the Life of Wenceslas fit with our understanding of concepts of justice amongst the Ottonian elite, and how might it have been received by the intended audiences? We know that it remained a text read at the highest levels thanks to the earliest extant manuscript of the work, a lavishly decorated eleventh-century work made for Emma of Bohemia, wife of Boleslav II (and nephew of the martyred Wenceslas). It also influenced many royal saints’ lives. In his disdain for corporal punishment, Gumpold presents Wenceslas as a king who involved himself in justice intimately. Janet L. Nelson made the case that in the tenth century, across Europe, writers of all stripes moved away from talking about justice in relation to kingship, and a greater emphasis on peacemaking. Viewed through this lens, the standard for kings to aspire to was less Solomon or David than New Testament Christological models, with their ’emphasis on a king’s humility as a man, rather than on his exercising of justice’. Although we know nothing of Gumpold beyond his status as an Italian bishop, the image he presents here is in line with broader lines of thought at the time, as authors clearly began to conceive of the role of the king in judicial processes in new ways, emphasising above all mercy as a key quality for kings to practice.

In Part 2 of the blog, next year, I’m going to continue to think about justice and Wenceslas, turning to the event of his martyrdom and his attitudes to parricide, which shaped much hagiography of royal saints, as well as Gumpold’s influences, and connections between Anglo-Saxon England and the Continent in this genre.