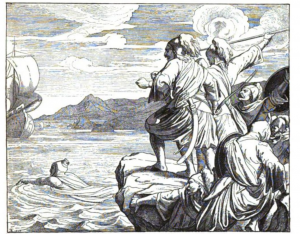

According to the chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg (III.20–1), in July 982 Emperor Otto II stood on a beach in Calabria, the southernmost region of mainland Italy. He had just suffered a disastrous loss against the forces of the emir of Sicily, Abū’l-Qāsim, whose soldiers had decimated the troops drawn from across Otto’s empire.

Otto flees the scene of the battle. From Illustrierte Weltgeschichte für das Volk, Otto von Corvin et al., III.489. Image licensed under Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Accompanied by a handful of loyal men, and with the victorious Saracen (Lat. Sarracenus) army at his back, the emperor rode out into the Ionian Sea on a horse borrowed from his follower Calonimus in the hope of being rescued. Otto was refused aid by a passing Greek ship, but was helped aboard another after recognising ‘his warrior Henry, whose Slavic name is Zolunta’, who helped disguise Otto and bring him abroad.

Otto’s presence in southern Italy in the early 980s had ostensibly been prompted by an appeal from Pope Benedict VII for support in the face of the growing threat in the south presented by the incursion of the Kalbid dynasty. Yet the prospect of extending the boundaries of his empire further at the expense of the Byzantine empire doubtlessly also played a part, and it may be significant that in the same year as the battle Otto’s chancery—men tasked with drafting diplomas—began to describe him as imperator Romanorum augustus with frequency, a title the emperor had in fact held since his coronation in Rome in 967. Otto’s initial skirmishes with Sicilian and Byzantine forces in late 981 were encouraging if not decisive, as indeed was the beginning of the fateful encounter in July 982 that occurred near Crotone, when the Kalbid army’s leader Emir Abu’l-Qasim was killed shortly after hostilities commenced; these successes and the enormous size of the Ottonian army that made their defeat the more shocking.

The Temple of Poseidon at Sunium (Cape Colonna) c.1834 J. M. W. Turner. Image © Tate CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Those killed in the battle included luminaries such as Bishop Henry of Augsburg, Count Udo II of Rheinfranken, and Margrave Gunther of Merseburg, as well as ‘innumerable others whose names are known only to God’. Thietmar also mentions the death of one Conrad, who is not identified any further, but was clearly of some importance given his inclusion in the named dead. It seems to me at least possible if not probable that this Conrad is the same individual as the homonymous Lotharingian mentioned in two tenth-century diplomas preserved in the Gorze cartulary, compiled in the later twelfth century, and the remainder of this post will focus on these documents for what they can tell us.

The earlier of the two diplomas, issued by Otto I in 946 (O I 80), granted land and a church at Longlier in Osning, said to be in the county of Rodulf, to the noblewoman Leva and her son Conrad. This diploma was issued thirty-five years prior to the battle in Calabria, which—if the two Conrads are one and the same—might explain Leva’s prominence in the document, if her son had not reached the age of majority. Alternatively, the Conrad described in the 982 document may have been a descendant.

The second diploma was issued by Otto II two months after his Calabrian defeat (O II 280). At Capua, Otto made over a large donation to the monastery of Gorze, including Longlier (‘Lunglar… in pago Osning’)—the same place donated in the diploma of his father to Leva and Conrad—at the bequest of his follower Conrad. The relevant portion of the diploma is translated below:

‘Let it be known to all present and future faithful that on the day of the battle which happened between us and the Saracens, Conrad, son of the former Count Rudolf, legally commended to be given to us all of his property which he held in the territory of Lothringia—under our banner, that is the imperial banner—and humbly asked our majesty, in the sight of the whole army that we would transfer by diploma all things small and large to the monastery of Saint Gorgon the martyr constructed in the place called Gorze, were he to die on that day, which he did. Talking about his petition after the battle with our faithful [we were convinced to issue it], firstly through the intervention of our beloved wife, the august Empress Theophanu, and then by the advice of our faithful, namely our nephew Duke Otto of Alemannia and Bavaria, the venerable Bishop Dietrich of Metz, and others dear to us…’

Otto II as depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493), Cambridge University Library (Inc.0.A.7.2[888]), f. 181r. Image licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0.

The diploma—unusually cinematic in its tone—offers to its modern-day readers a wealth of information about the way tenth-century elites conceptualized and articulated their past. Conrad’s request of Otto to take care of his inheritance, which occurred if not on the battlefield itself then certainly during preparations, is described by the draftsman as having taken place under the imperial banner. Here, as elsewhere, the draftsman seems to have a keen sense for narrative and storytelling in general, moving events from Conrad’s request to the defeat itself (evidently a delicate issue mentioned only cursorily), and then to Otto’s discussion of the matter first with Empress Theophanu and then with his followers. The text also reveals the mutual importance and interweaving roles of speech and the written word. Conrad’s oral request that Otto fulfils his wishes is supplemented by his desire that this grant be made in writing to the monastery. That Otto does this in the form of a diploma, acceding to Conrad’s request, emphasises the importance of such donations taking written form. But speech and discussion also clearly play a vital role not just for Conrad, whose petition on the eve of battlefield naturally lent itself to discussion rather than written request, but also in the stylised representation of the debate over whether the will should be enforced, conducted between emperor and empress and then emperor and followers.

The narratio of the diploma, then, shows us an unusually personal piece of evidence for the impact of the battle on the Ottonian elite, otherwise known to us only through Thietmar’s text and a garbled account by the thirteenth-century historian Ibn al-Athir. Although this is not the only tenth-century diploma to refer to a changed political situation caused by conflict between Ottonian forces and their enemies, whether Hungarian, Slavic or Sicilian, it is unique in combining reference to a military defeat for the Ottonians, in its attention to narrative and chronology, and in its nuanced and unusual presentation of inheritance and the interplay of oral and written.

.